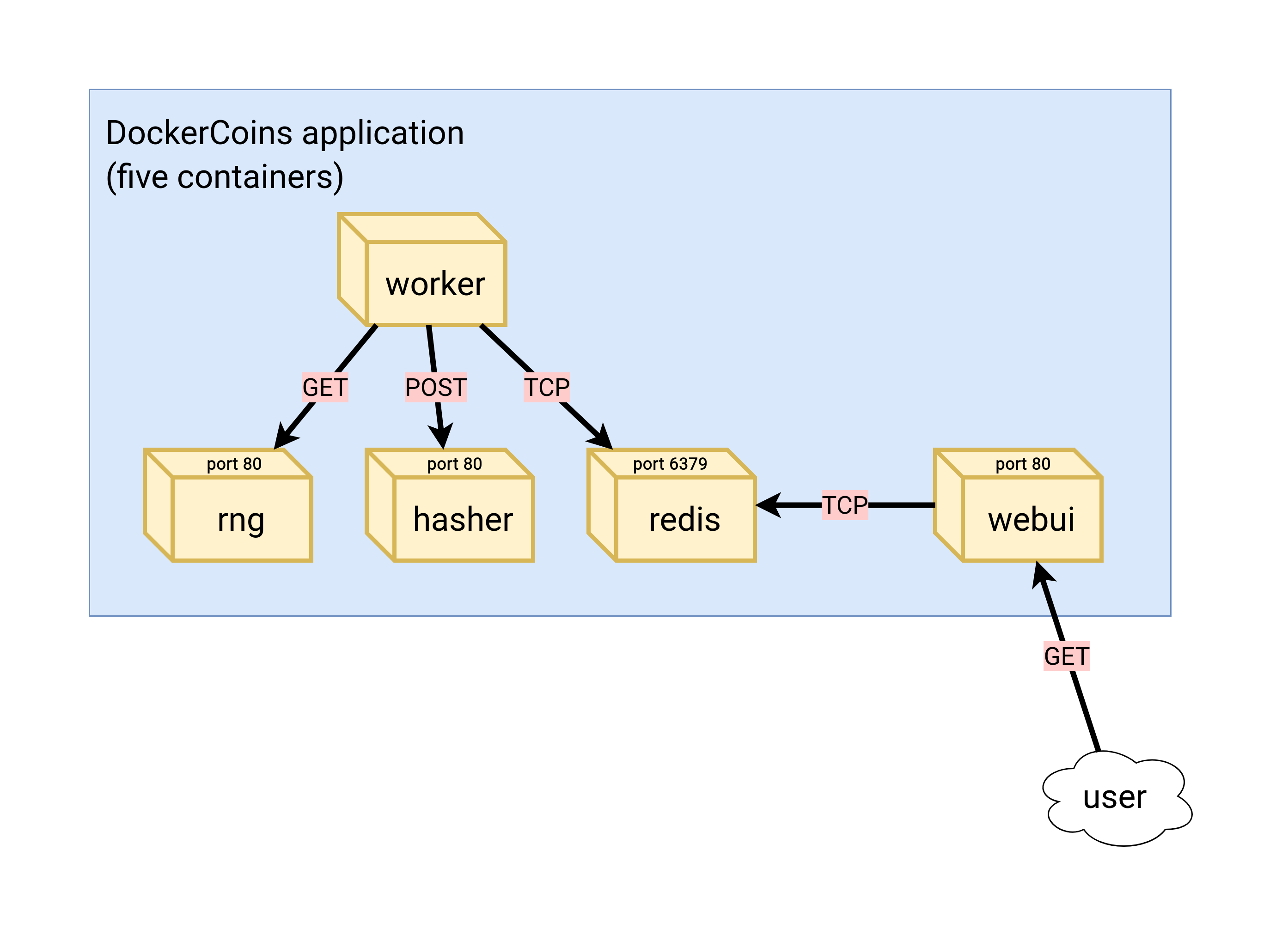

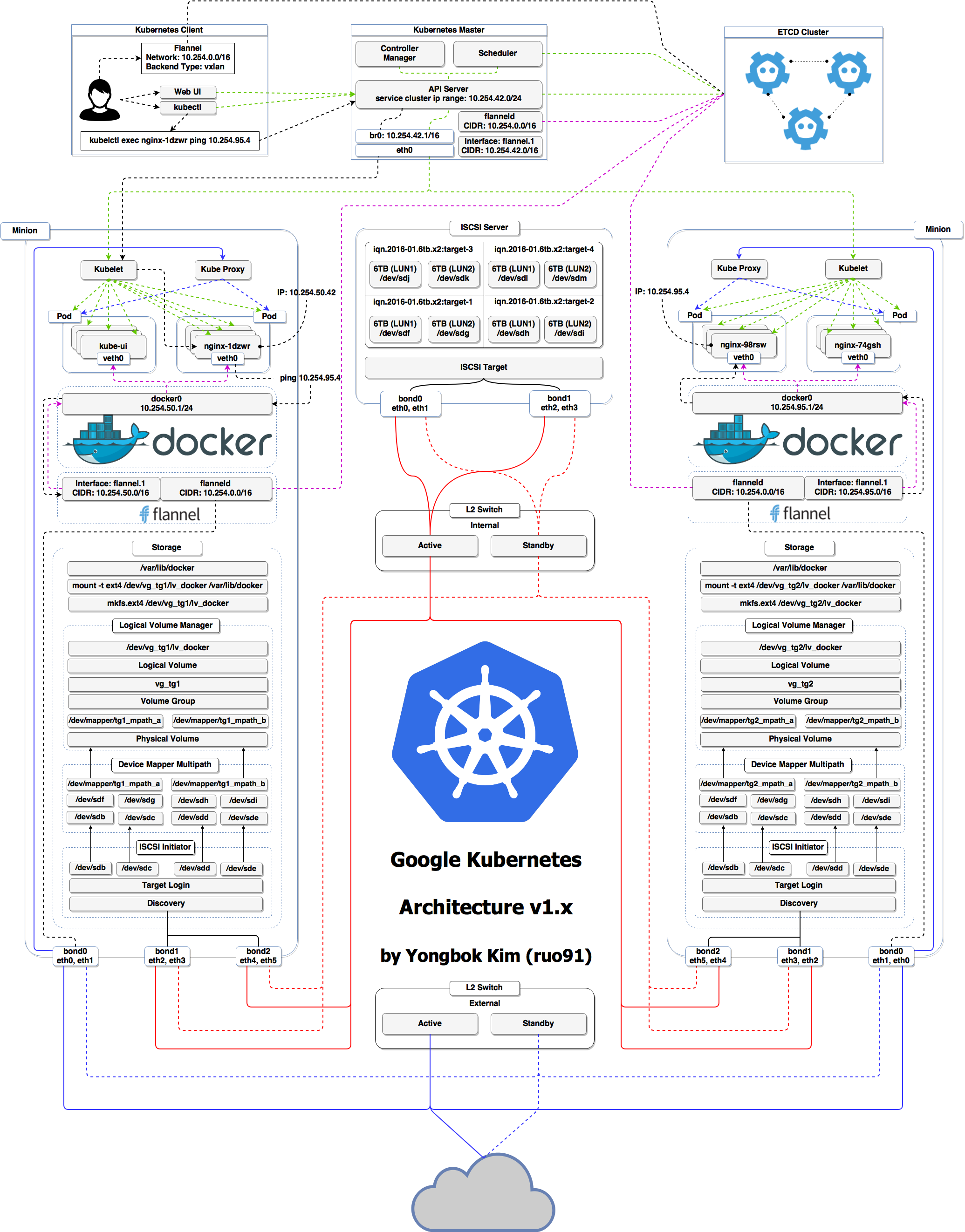

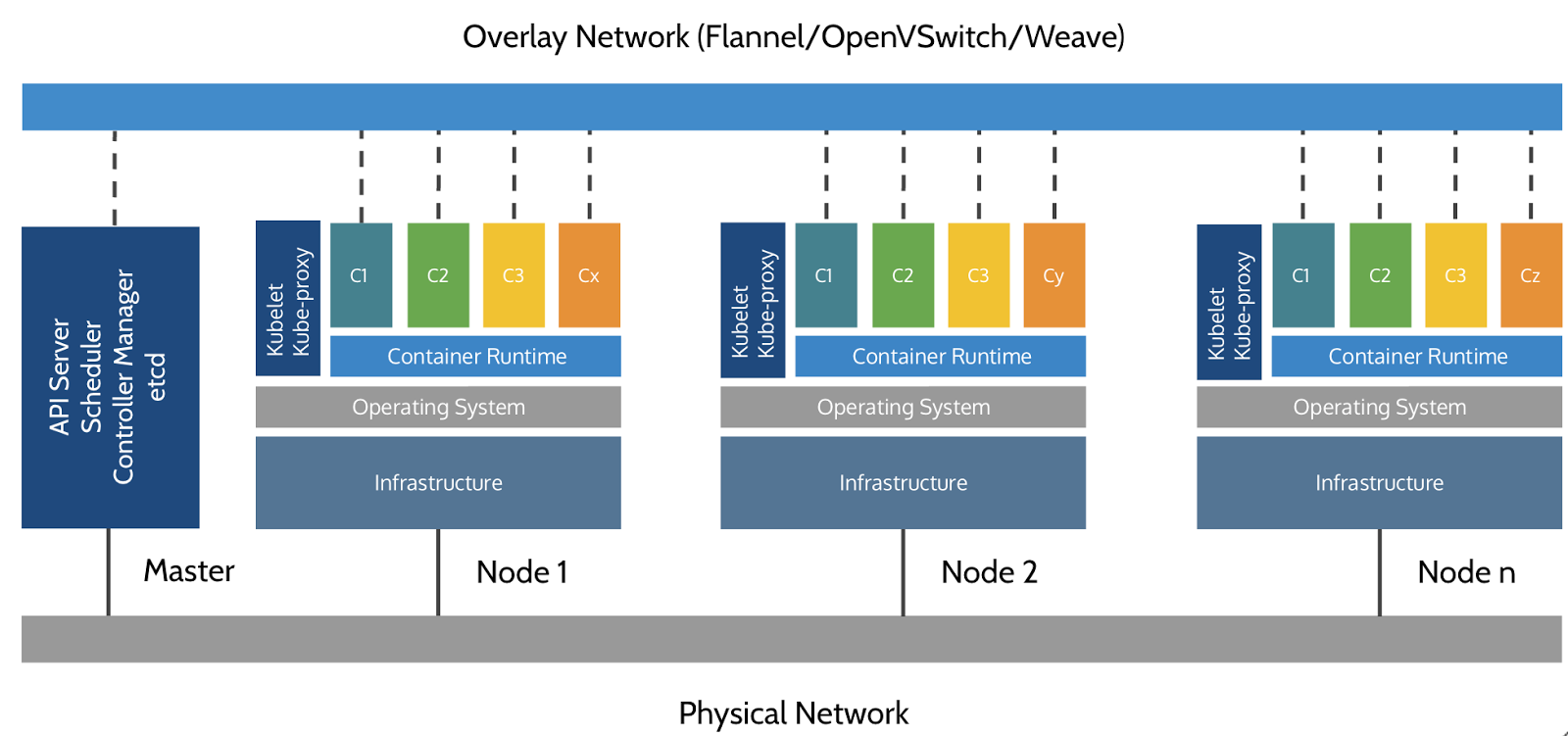

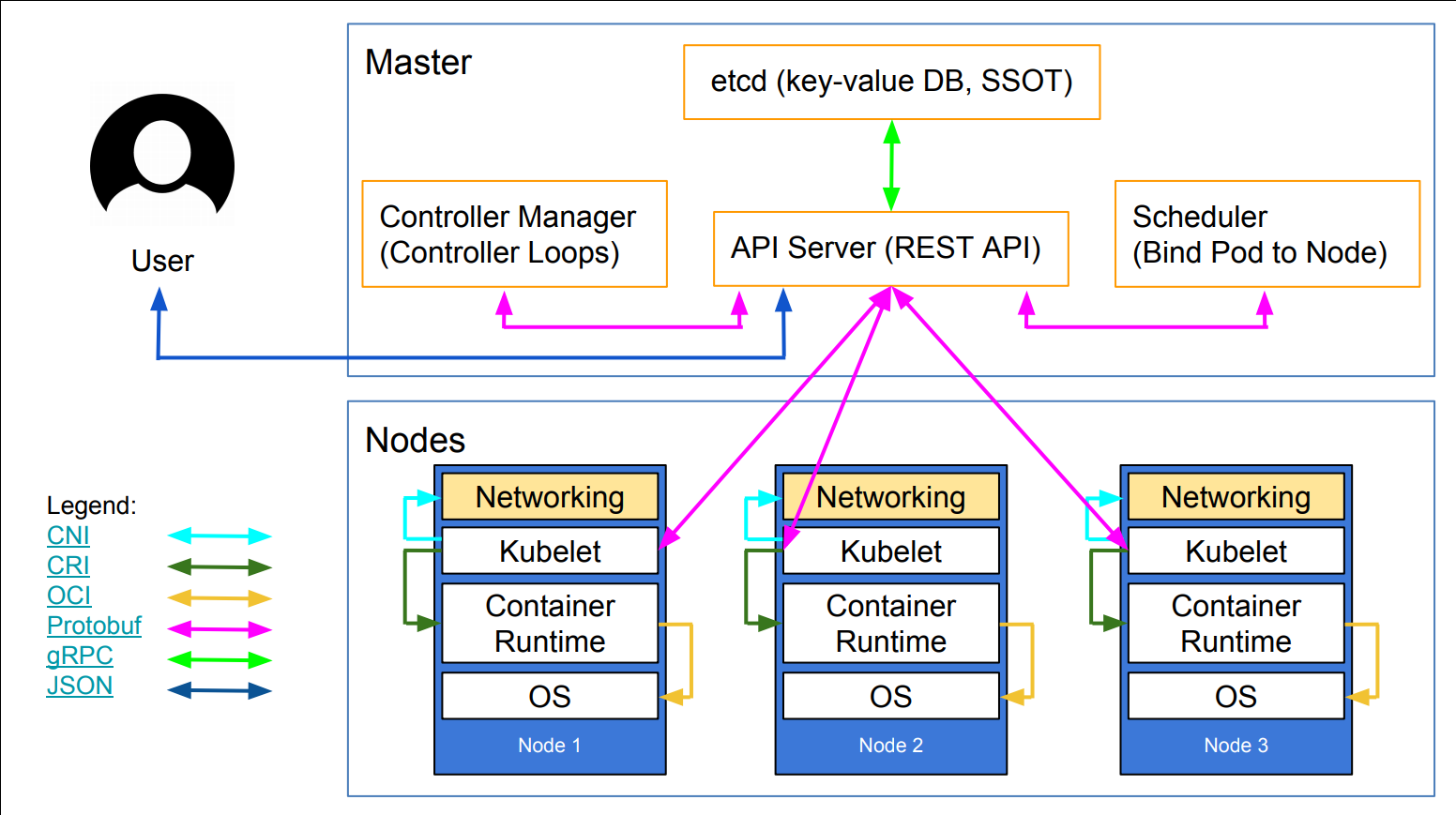

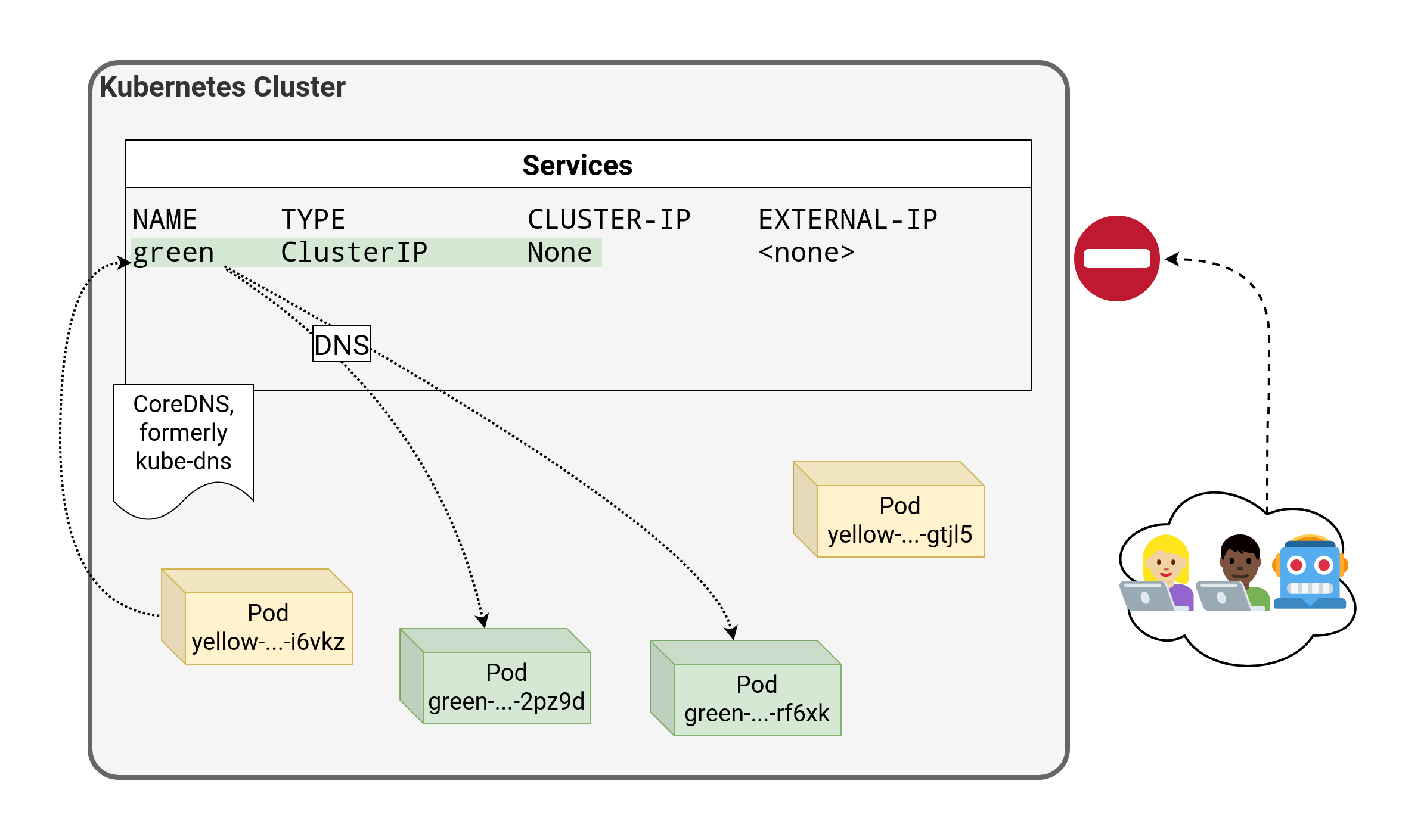

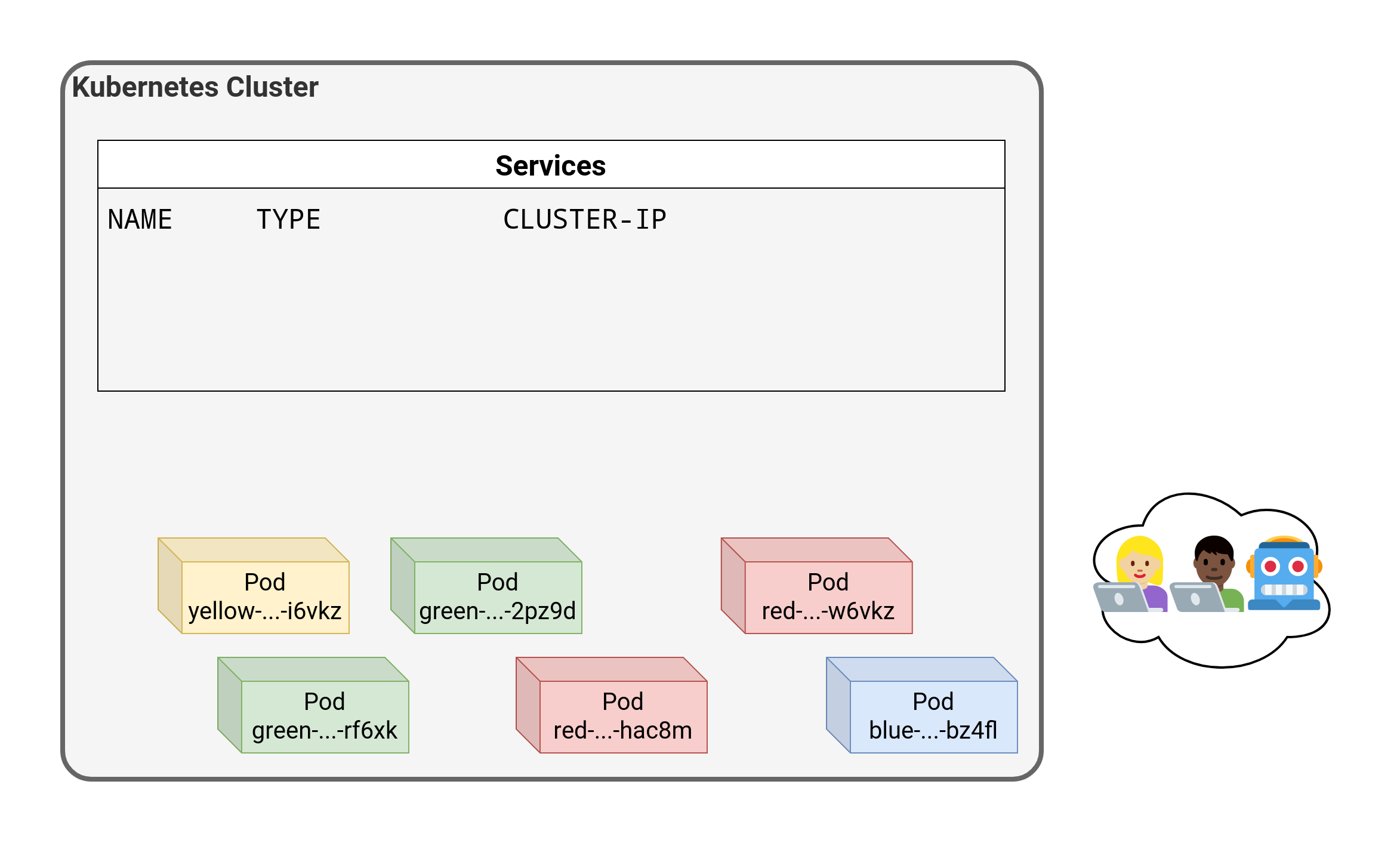

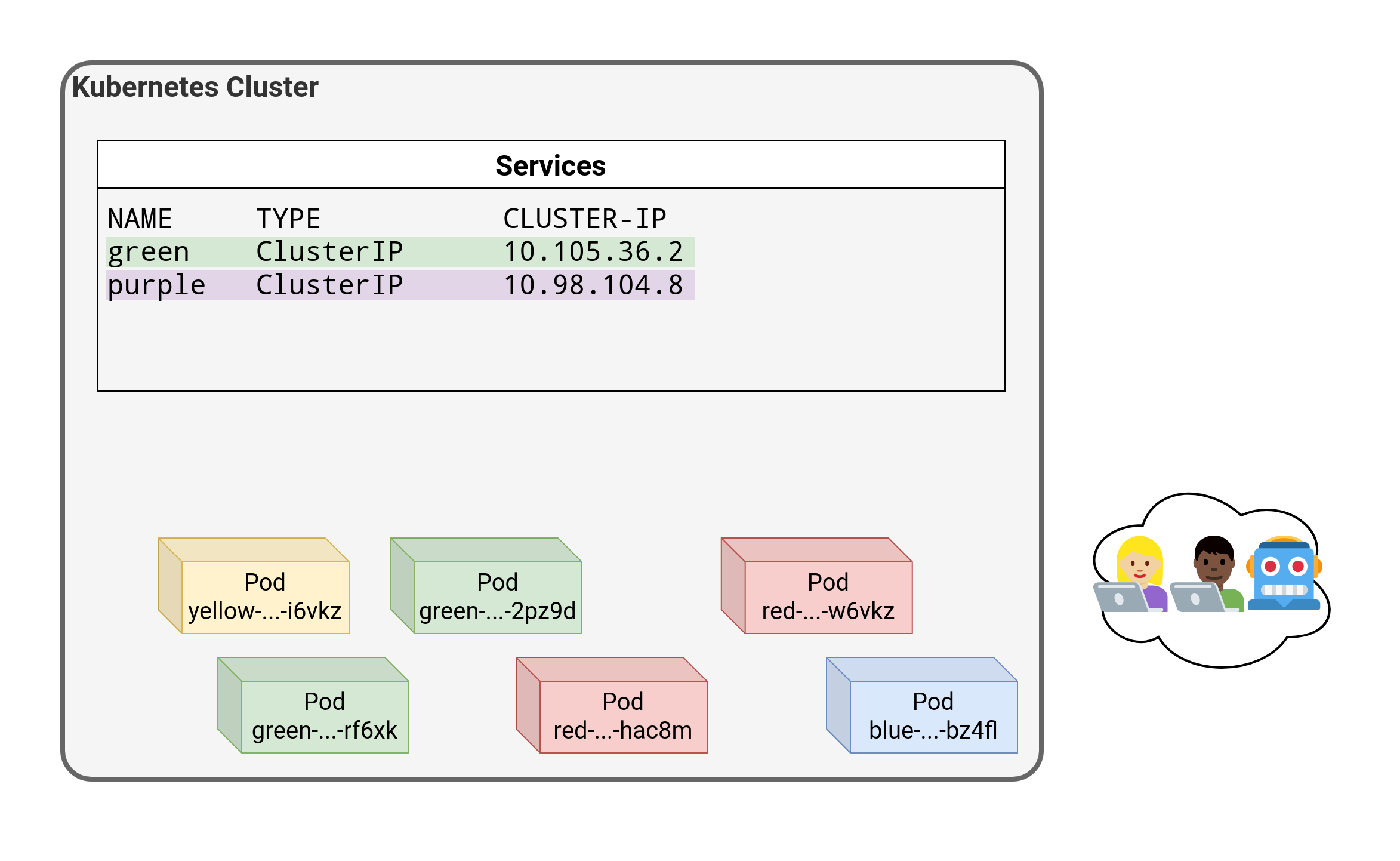

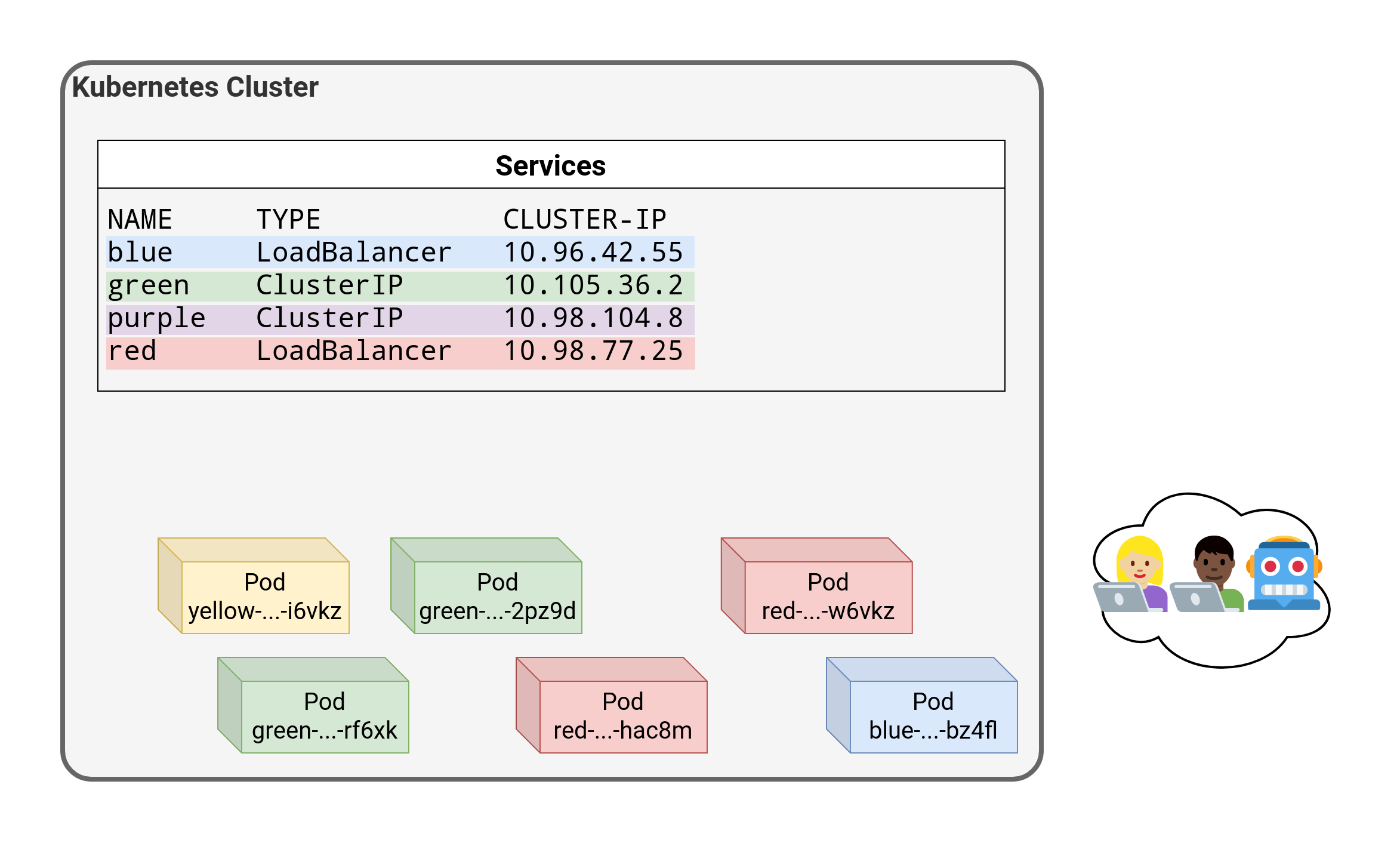

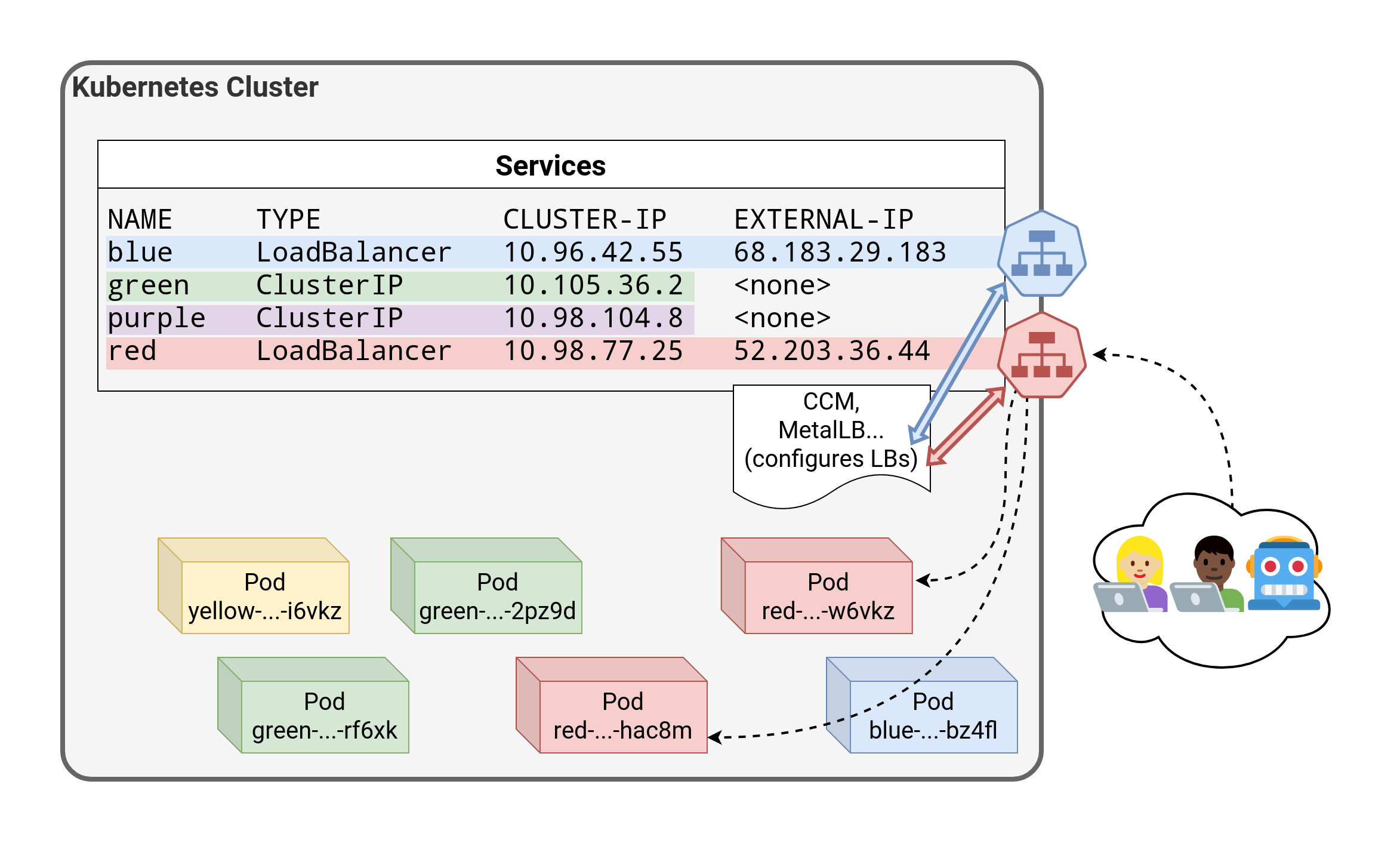

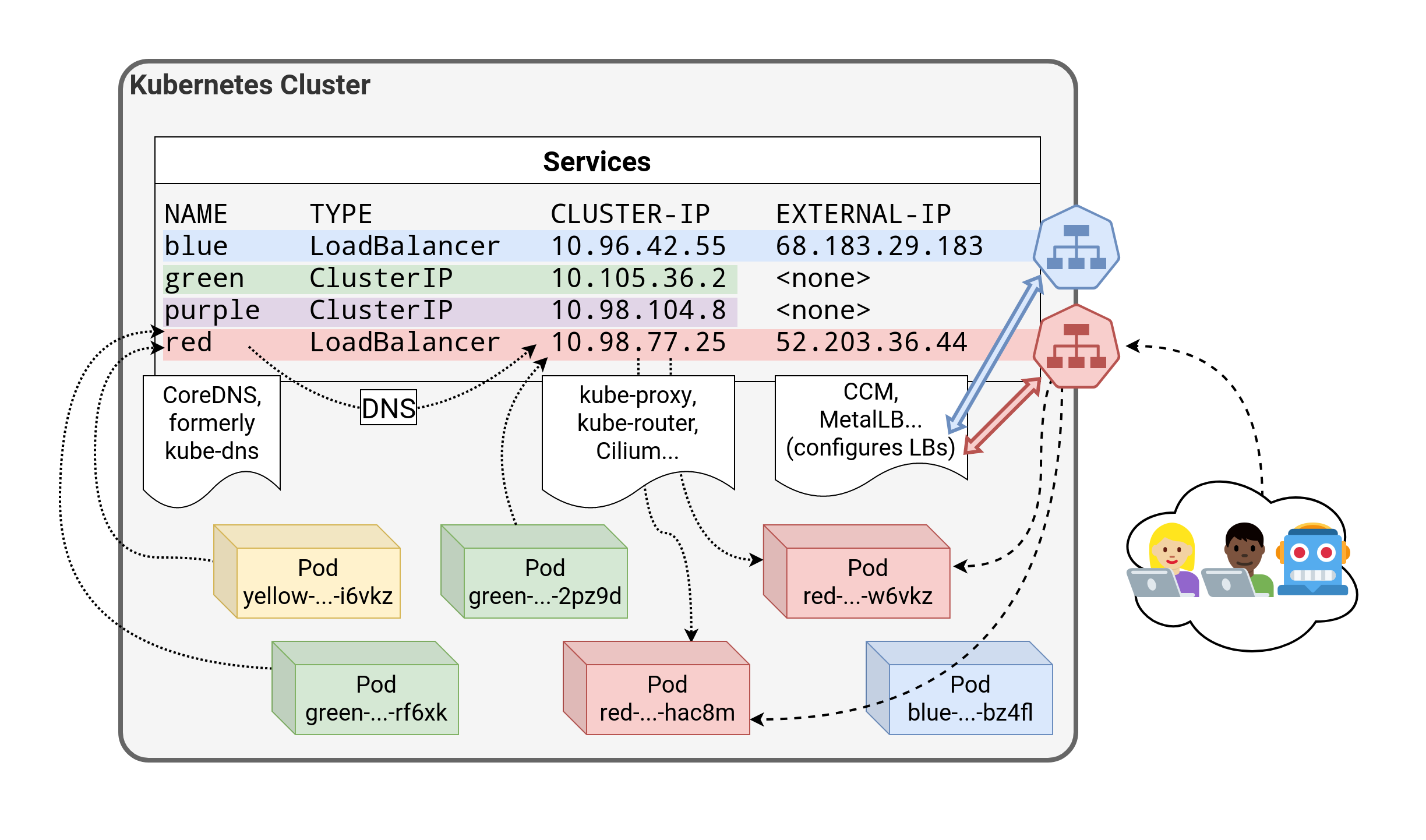

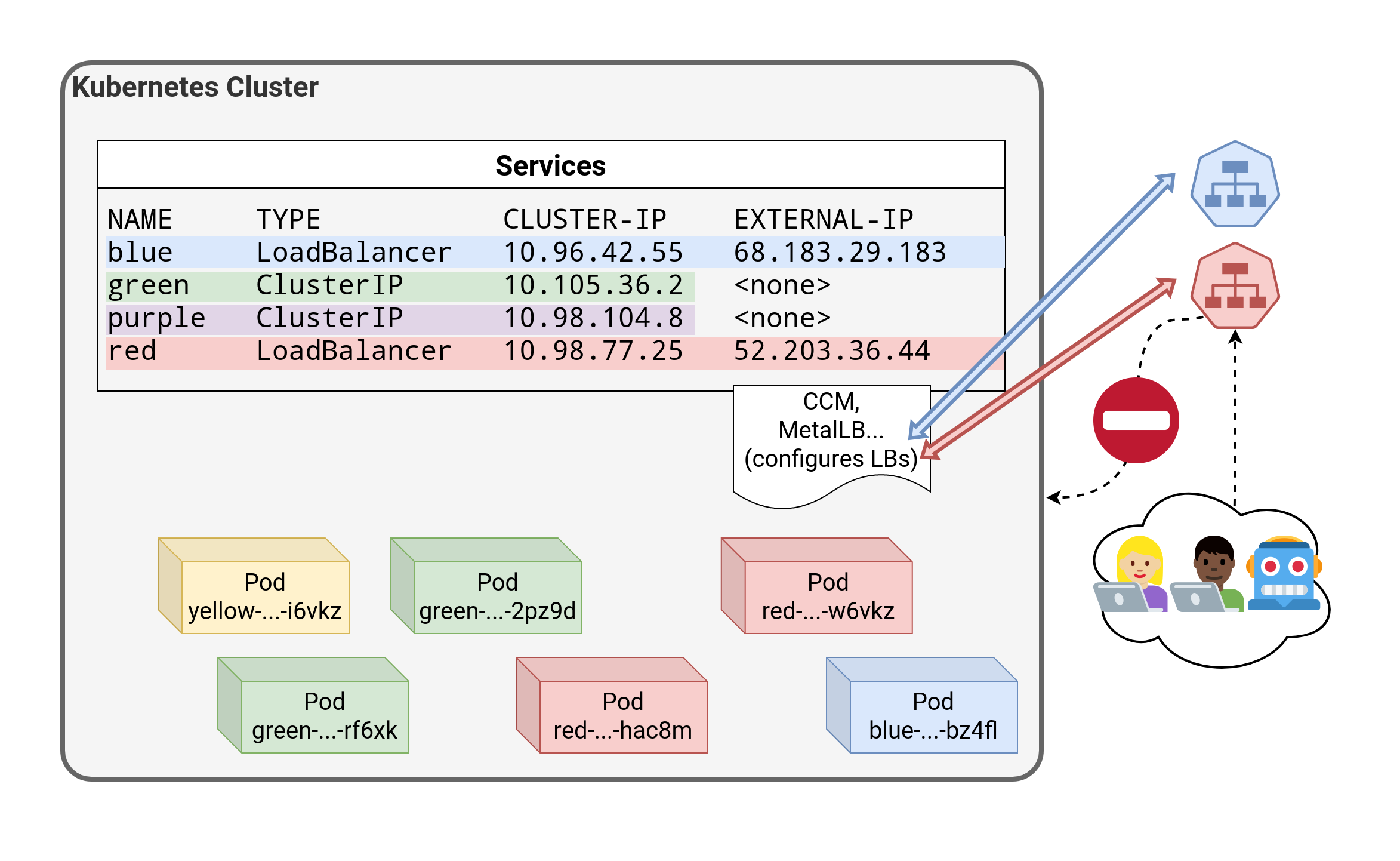

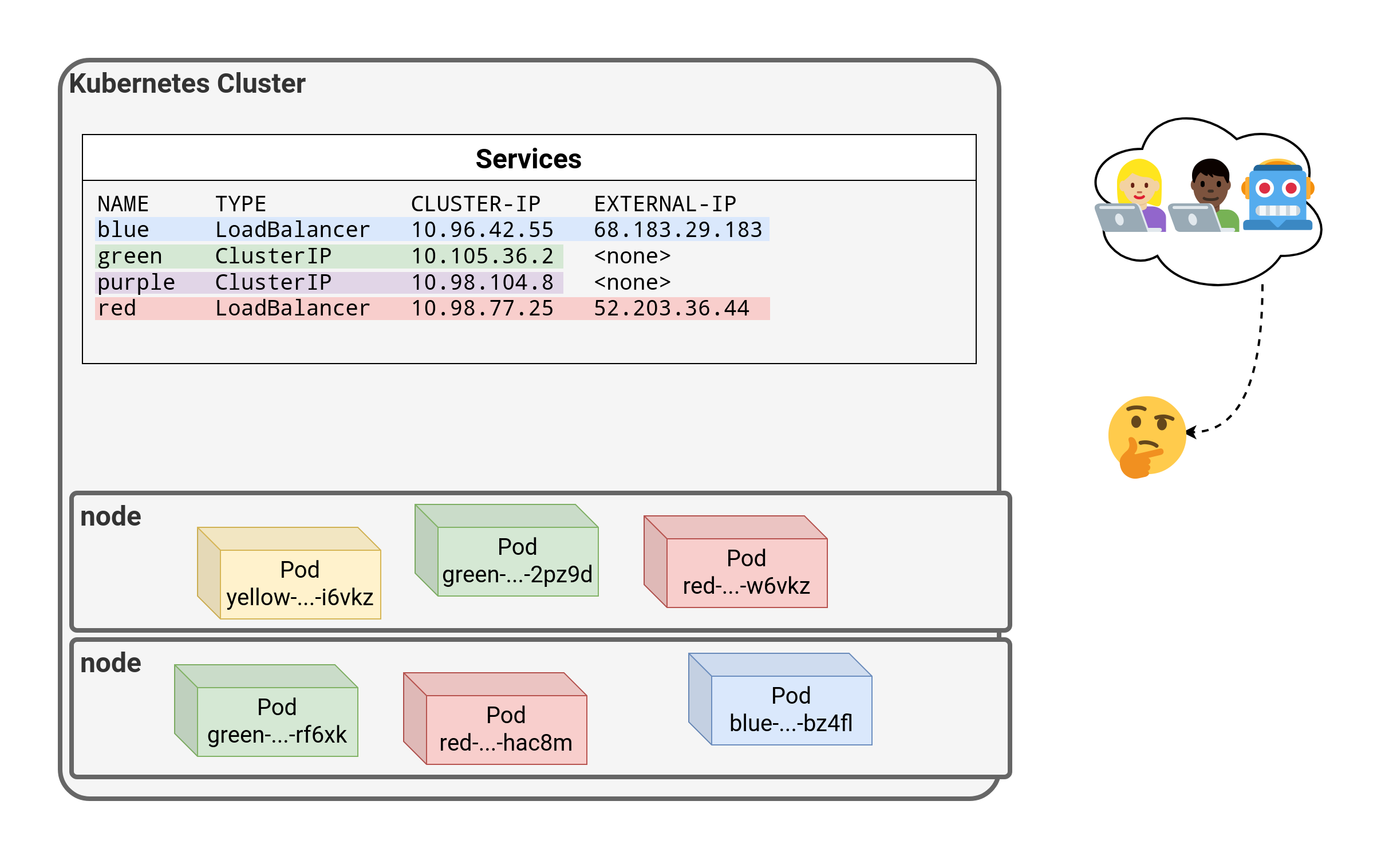

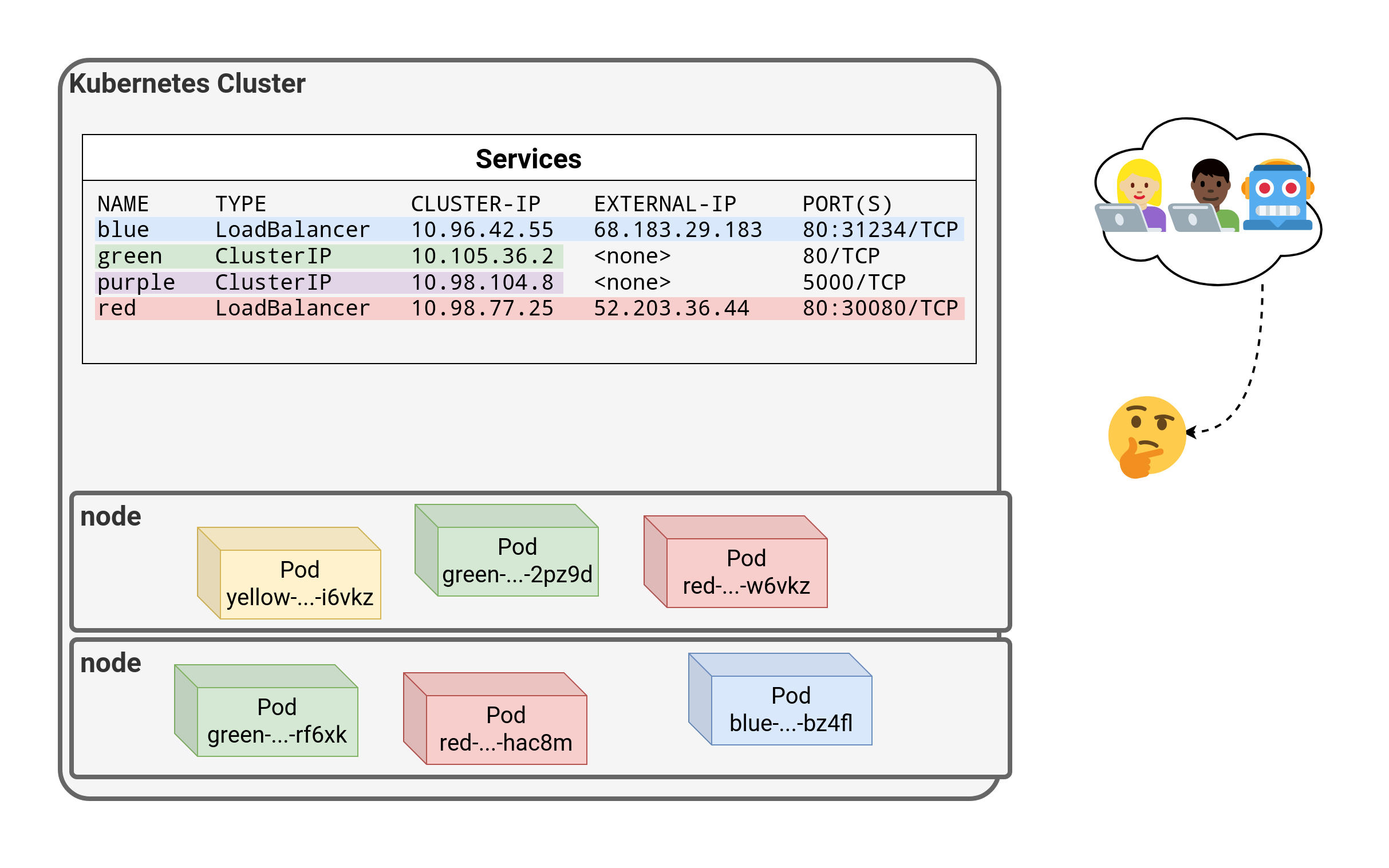

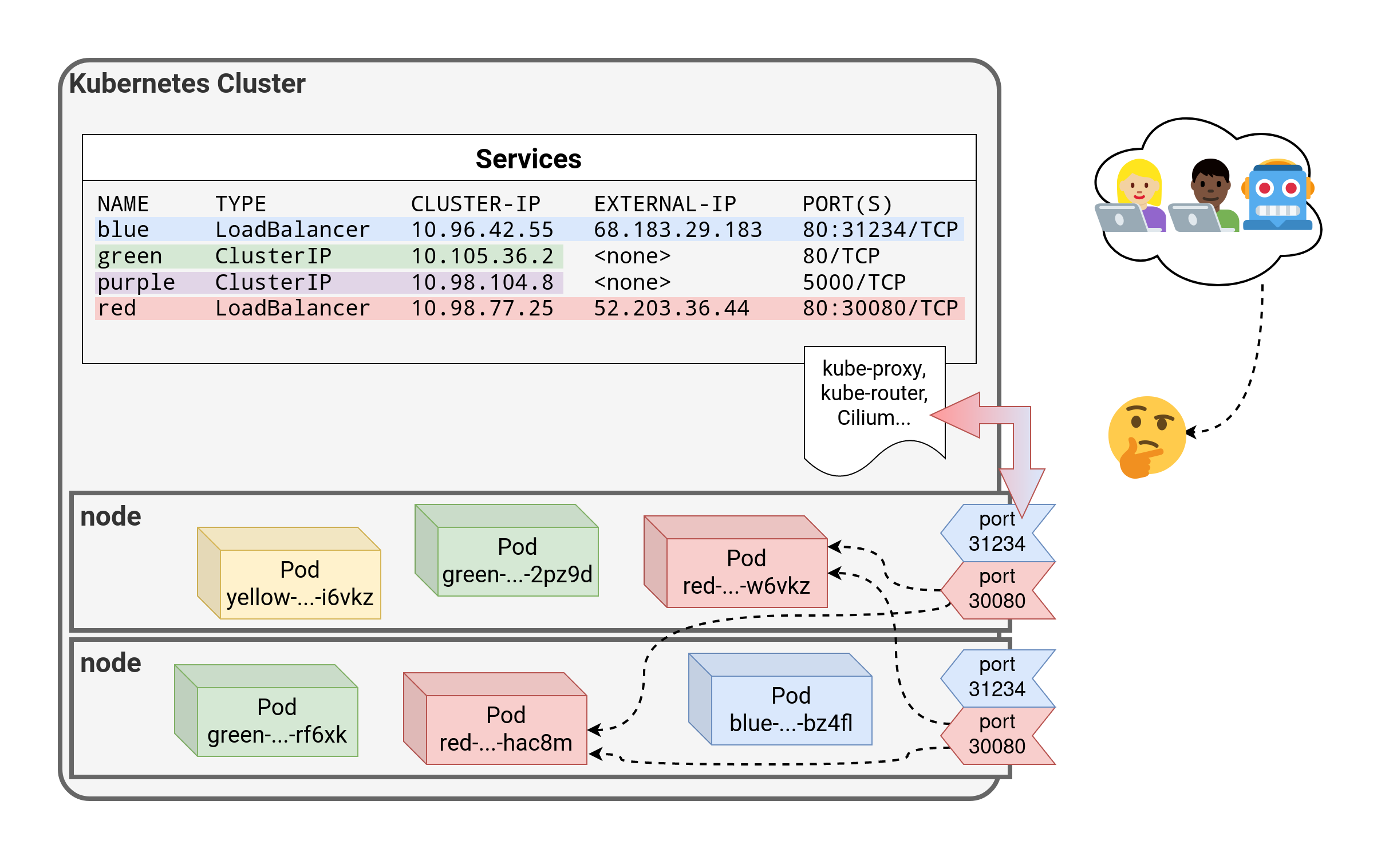

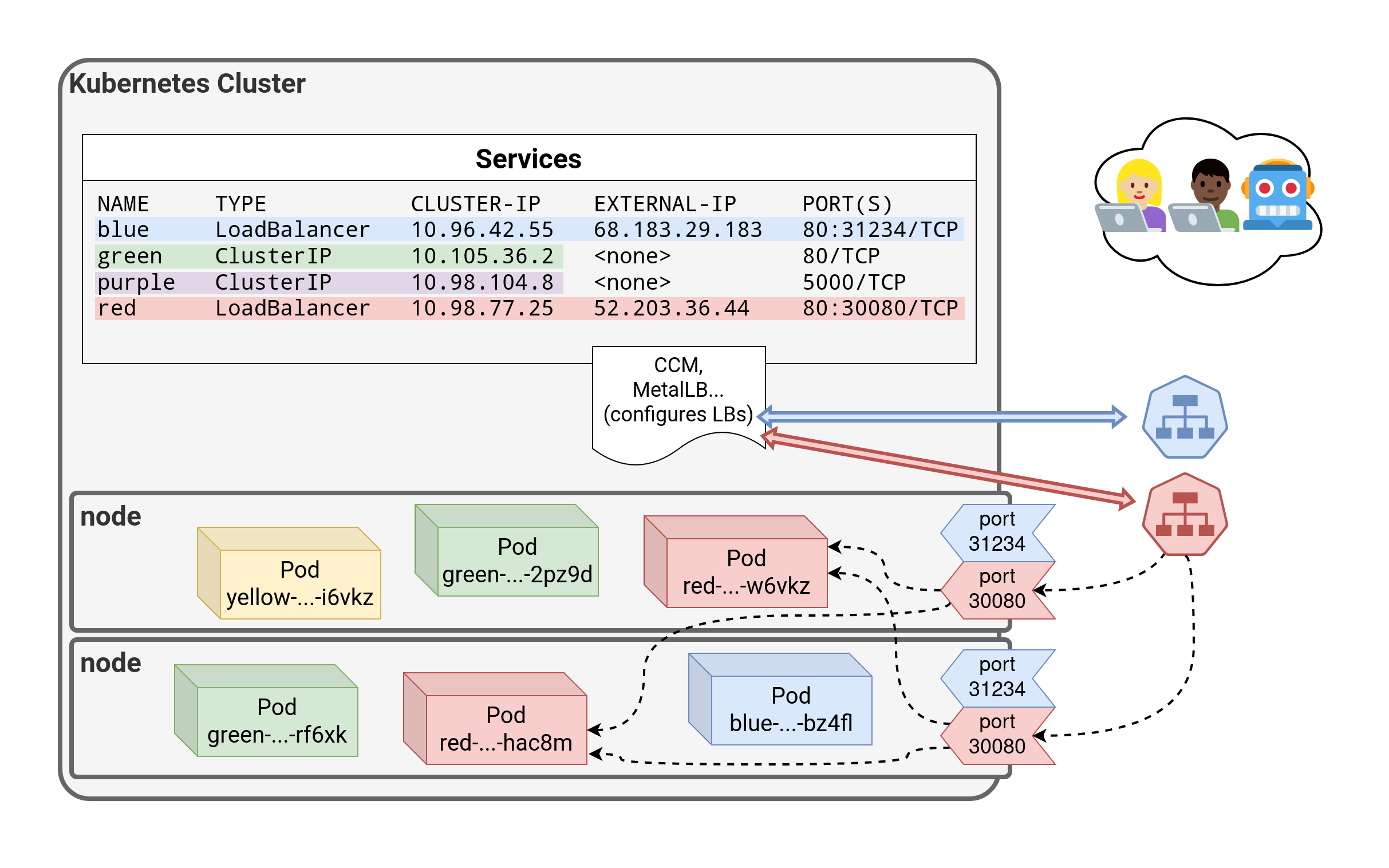

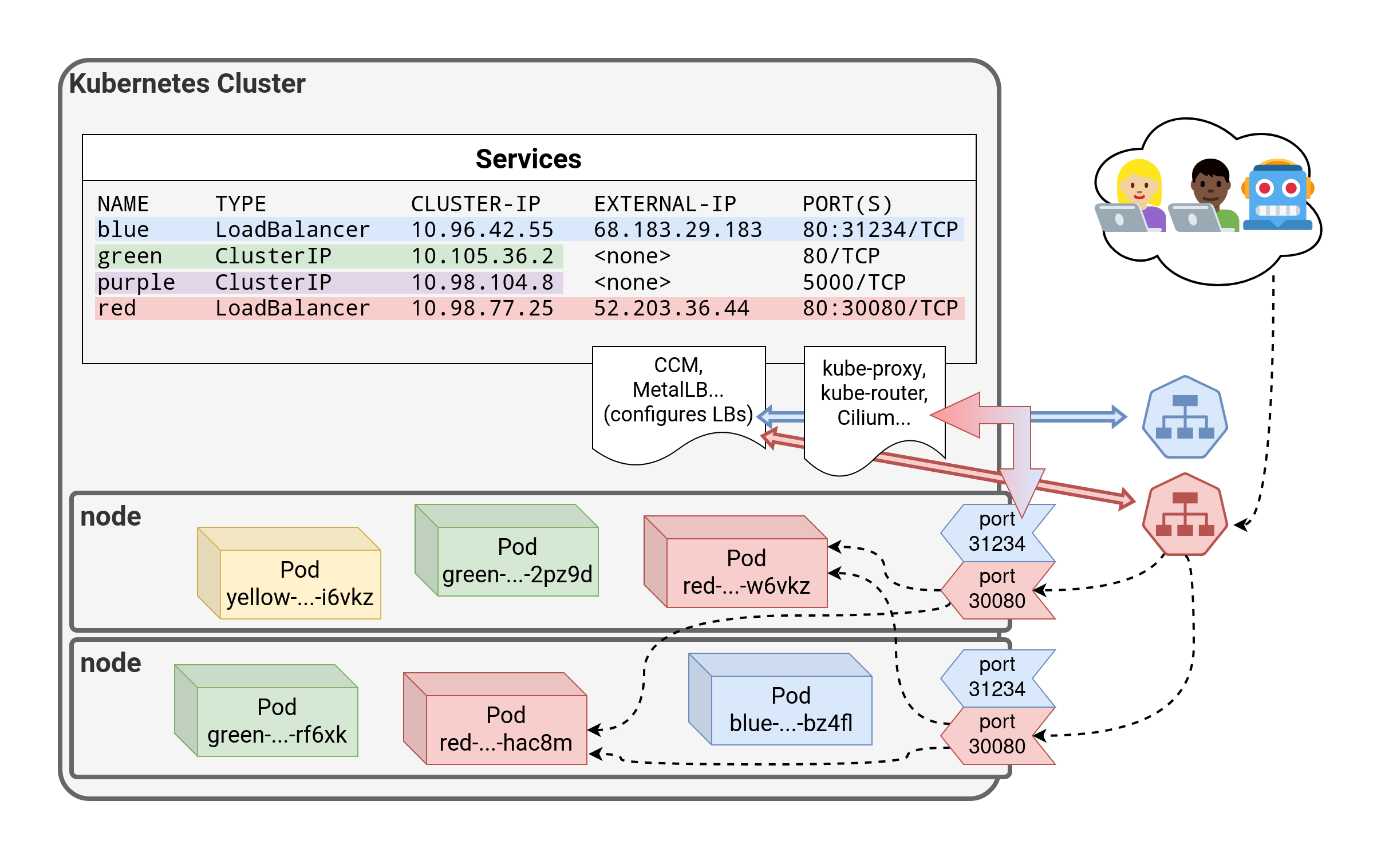

class: title, self-paced Kubernetes Training<br/> .nav[*Self-paced version*] .debug[ ``` ``` These slides have been built from commit: e562ec2 [shared/title.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/title.md)] --- class: title, in-person Kubernetes Training<br/><br/></br> .footnote[ **Slides[:](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h16zyxiwDLY) https://2022-11-live.container.training/** ] <!-- WiFi: **Something**<br/> Password: **Something** **Be kind to the WiFi!**<br/> *Use the 5G network.* *Don't use your hotspot.*<br/> *Don't stream videos or download big files during the workshop*<br/> *Thank you!* --> .debug[[shared/title.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/title.md)] --- ## Introductions - Hello! We are: - 👷🏻♀️ AJ ([@s0ulshake], [EphemeraSearch], [Quantgene]) - 👩🏼🔬 Dana ([@bigdana]) - 🐳 Jérôme ([@jpetazzo], Tiny Shell Script LLC) - Live feedback, questions, help: [Mattermost](https://live.container.training/mattermost) (ask questions on the public channel so that AJ & Dana can see them; <br/>they have more production experience than me, especially on k8s :)) - Feel free to send questions at any time! .debug[[logistics.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/logistics.md)] --- ## Schedule | Pacific | Eastern | | |-----------|-----------|-------------------| | 8am-10am | 11am-1pm | First period | | 10am-11am | 1pm-2pm | Long break | | 11am-1pm | 2pm-4pm | Second period | | After 1pm | After 4pm | Homework, labs... | We'll also have short breaks in the middle of each period. <!-- --> [EphemeraSearch]: https://ephemerasearch.com/ [@jpetazzo]: https://mastodon.social/@jpetazzo [@s0ulshake]: https://twitter.com/s0ulshake [Quantgene]: https://www.quantgene.com/ [@bigdana]: https://twitter.com/bigdana .debug[[logistics.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/logistics.md)] --- ## Exercises - At the end of each day, there is a series of exercises - To make the most out of the training, please try the exercises! (it will help to practice and memorize the content of the day) - We recommend to take at least one hour to work on the exercises (if you understood the content of the day, it will be much faster) - Each day will start with a quick review of the exercises of the previous day .debug[[logistics.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/logistics.md)] --- ## A brief introduction - This was initially written by [Jérôme Petazzoni](https://twitter.com/jpetazzo) to support in-person, instructor-led workshops and tutorials - Credit is also due to [multiple contributors](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/graphs/contributors) — thank you! - You can also follow along on your own, at your own pace - We included as much information as possible in these slides - We recommend having a mentor to help you ... - ... Or be comfortable spending some time reading the Kubernetes [documentation](https://kubernetes.io/docs/) ... - ... And looking for answers on [StackOverflow](http://stackoverflow.com/questions/tagged/kubernetes) and other outlets .debug[[k8s/intro.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/intro.md)] --- class: self-paced ## Hands on, you shall practice - Nobody ever became a Jedi by spending their lives reading Wookiepedia - Likewise, it will take more than merely *reading* these slides to make you an expert - These slides include *tons* of demos, exercises, and examples - They assume that you have access to a Kubernetes cluster - If you are attending a workshop or tutorial: <br/>you will be given specific instructions to access your cluster - If you are doing this on your own: <br/>the first chapter will give you various options to get your own cluster .debug[[k8s/intro.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/intro.md)] --- ## Accessing these slides now - We recommend that you open these slides in your browser: https://2022-11-live.container.training/ - Use arrows to move to next/previous slide (up, down, left, right, page up, page down) - Type a slide number + ENTER to go to that slide - The slide number is also visible in the URL bar (e.g. .../#123 for slide 123) .debug[[shared/about-slides.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/about-slides.md)] --- ## Accessing these slides later - Slides will remain online so you can review them later if needed (let's say we'll keep them online at least 1 year, how about that?) - You can download the slides using that URL: https://2022-11-live.container.training/slides.zip (then open the file `kube.yml.html`) - You will find new versions of these slides on: https://container.training/ .debug[[shared/about-slides.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/about-slides.md)] --- ## These slides are open source - You are welcome to use, re-use, share these slides - These slides are written in Markdown - The sources of these slides are available in a public GitHub repository: https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training - Typos? Mistakes? Questions? Feel free to hover over the bottom of the slide ... .footnote[👇 Try it! The source file will be shown and you can view it on GitHub and fork and edit it.] <!-- .lab[ ```open https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/master/slides/common/about-slides.md``` ] --> .debug[[shared/about-slides.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/about-slides.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Extra details - This slide has a little magnifying glass in the top left corner - This magnifying glass indicates slides that provide extra details - Feel free to skip them if: - you are in a hurry - you are new to this and want to avoid cognitive overload - you want only the most essential information - You can review these slides another time if you want, they'll be waiting for you ☺ .debug[[shared/about-slides.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/about-slides.md)] --- ## Chat room - We've set up a chat room that we will monitor during the workshop - Don't hesitate to use it to ask questions, or get help, or share feedback - The chat room will also be available after the workshop - Join the chat room: [Mattermost](https://live.container.training/mattermost) - Say hi in the chat room! .debug[[shared/chat-room-im.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/chat-room-im.md)] --- ## Pre-requirements - Be comfortable with the UNIX command line - navigating directories - editing files - a little bit of bash-fu (environment variables, loops) - Some Docker knowledge - `docker run`, `docker ps`, `docker build` - ideally, you know how to write a Dockerfile and build it <br/> (even if it's a `FROM` line and a couple of `RUN` commands) - It's totally OK if you are not a Docker expert! .debug[[shared/prereqs.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/prereqs.md)] --- class: title *Tell me and I forget.* <br/> *Teach me and I remember.* <br/> *Involve me and I learn.* Misattributed to Benjamin Franklin [(Probably inspired by Chinese Confucian philosopher Xunzi)](https://www.barrypopik.com/index.php/new_york_city/entry/tell_me_and_i_forget_teach_me_and_i_may_remember_involve_me_and_i_will_lear/) .debug[[shared/prereqs.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/prereqs.md)] --- ## Hands-on sections - The whole workshop is hands-on - We are going to build, ship, and run containers! - You are invited to reproduce all the demos - All hands-on sections are clearly identified, like the gray rectangle below .lab[ - This is the stuff you're supposed to do! - Go to https://2022-11-live.container.training/ to view these slides <!-- ```open https://2022-11-live.container.training/``` --> ] .debug[[shared/prereqs.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/prereqs.md)] --- class: in-person ## Where are we going to run our containers? .debug[[shared/prereqs.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/prereqs.md)] --- class: in-person, pic  .debug[[shared/prereqs.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/prereqs.md)] --- class: in-person ## You get a cluster of cloud VMs - Each person gets a private cluster of cloud VMs (not shared with anybody else) - They'll remain up for the duration of the workshop - You should have a little card with login+password+IP addresses - You can automatically SSH from one VM to another - The nodes have aliases: `node1`, `node2`, etc. .debug[[shared/prereqs.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/prereqs.md)] --- class: in-person ## Why don't we run containers locally? - Installing this stuff can be hard on some machines (32 bits CPU or OS... Laptops without administrator access... etc.) - *"The whole team downloaded all these container images from the WiFi! <br/>... and it went great!"* (Literally no-one ever) - All you need is a computer (or even a phone or tablet!), with: - an Internet connection - a web browser - an SSH client .debug[[shared/prereqs.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/prereqs.md)] --- class: in-person ## SSH clients - On Linux, OS X, FreeBSD... you are probably all set - On Windows, get one of these: - [putty](http://www.putty.org/) - Microsoft [Win32 OpenSSH](https://github.com/PowerShell/Win32-OpenSSH/wiki/Install-Win32-OpenSSH) - [Git BASH](https://git-for-windows.github.io/) - [MobaXterm](http://mobaxterm.mobatek.net/) - On Android, [JuiceSSH](https://juicessh.com/) ([Play Store](https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.sonelli.juicessh)) works pretty well - Nice-to-have: [Mosh](https://mosh.org/) instead of SSH, if your Internet connection tends to lose packets .debug[[shared/prereqs.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/prereqs.md)] --- class: in-person, extra-details ## What is this Mosh thing? *You don't have to use Mosh or even know about it to follow along. <br/> We're just telling you about it because some of us think it's cool!* - Mosh is "the mobile shell" - It is essentially SSH over UDP, with roaming features - It retransmits packets quickly, so it works great even on lossy connections (Like hotel or conference WiFi) - It has intelligent local echo, so it works great even in high-latency connections (Like hotel or conference WiFi) - It supports transparent roaming when your client IP address changes (Like when you hop from hotel to conference WiFi) .debug[[shared/prereqs.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/prereqs.md)] --- class: in-person, extra-details ## Using Mosh - To install it: `(apt|yum|brew) install mosh` - It has been pre-installed on the VMs that we are using - To connect to a remote machine: `mosh user@host` (It is going to establish an SSH connection, then hand off to UDP) - It requires UDP ports to be open (By default, it uses a UDP port between 60000 and 61000) .debug[[shared/prereqs.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/prereqs.md)] --- class: in-person ## Connecting to our lab environment .lab[ - Log into the first VM (`node1`) with your SSH client: ```bash ssh `user`@`A.B.C.D` ``` (Replace `user` and `A.B.C.D` with the user and IP address provided to you) <!-- ```bash for N in $(awk '/\Wnode/{print $2}' /etc/hosts); do ssh -o StrictHostKeyChecking=no $N true done ``` ```bash ### FIXME find a way to reset the cluster, maybe? ``` --> ] You should see a prompt looking like this: ``` [A.B.C.D] (...) user@node1 ~ $ ``` If anything goes wrong — ask for help! .debug[[shared/connecting.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/connecting.md)] --- class: in-person ## `tailhist` - The shell history of the instructor is available online in real time - Note the IP address of the instructor's virtual machine (A.B.C.D) - Open http://A.B.C.D:1088 in your browser and you should see the history - The history is updated in real time (using a WebSocket connection) - It should be green when the WebSocket is connected (if it turns red, reloading the page should fix it) .debug[[shared/connecting.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/connecting.md)] --- ## Doing or re-doing the workshop on your own? - Use something like [Play-With-Docker](http://play-with-docker.com/) or [Play-With-Kubernetes](https://training.play-with-kubernetes.com/) Zero setup effort; but environment are short-lived and might have limited resources - Create your own cluster (local or cloud VMs) Small setup effort; small cost; flexible environments - Create a bunch of clusters for you and your friends ([instructions](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/master/prepare-vms)) Bigger setup effort; ideal for group training .debug[[shared/connecting.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/connecting.md)] --- ## For a consistent Kubernetes experience ... - If you are using your own Kubernetes cluster, you can use [jpetazzo/shpod](https://github.com/jpetazzo/shpod) - `shpod` provides a shell running in a pod on your own cluster - It comes with many tools pre-installed (helm, stern...) - These tools are used in many demos and exercises in these slides - `shpod` also gives you completion and a fancy prompt - It can also be used as an SSH server if needed .debug[[shared/connecting.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/connecting.md)] --- class: self-paced ## Get your own Docker nodes - If you already have some Docker nodes: great! - If not: let's get some thanks to Play-With-Docker .lab[ - Go to http://www.play-with-docker.com/ - Log in - Create your first node <!-- ```open http://www.play-with-docker.com/``` --> ] You will need a Docker ID to use Play-With-Docker. (Creating a Docker ID is free.) .debug[[shared/connecting.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/connecting.md)] --- ## We will (mostly) interact with node1 only *These remarks apply only when using multiple nodes, of course.* - Unless instructed, **all commands must be run from the first VM, `node1`** - We will only check out/copy the code on `node1` - During normal operations, we do not need access to the other nodes - If we had to troubleshoot issues, we would use a combination of: - SSH (to access system logs, daemon status...) - Docker API (to check running containers and container engine status) .debug[[shared/connecting.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/connecting.md)] --- ## Terminals Once in a while, the instructions will say: <br/>"Open a new terminal." There are multiple ways to do this: - create a new window or tab on your machine, and SSH into the VM; - use screen or tmux on the VM and open a new window from there. You are welcome to use the method that you feel the most comfortable with. .debug[[shared/connecting.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/connecting.md)] --- ## Tmux cheat sheet [Tmux](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tmux) is a terminal multiplexer like `screen`. *You don't have to use it or even know about it to follow along. <br/> But some of us like to use it to switch between terminals. <br/> It has been preinstalled on your workshop nodes.* - Ctrl-b c → creates a new window - Ctrl-b n → go to next window - Ctrl-b p → go to previous window - Ctrl-b " → split window top/bottom - Ctrl-b % → split window left/right - Ctrl-b Alt-1 → rearrange windows in columns - Ctrl-b Alt-2 → rearrange windows in rows - Ctrl-b arrows → navigate to other windows - Ctrl-b , → rename window - Ctrl-b d → detach session - tmux attach → re-attach to session .debug[[shared/connecting.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/connecting.md)] --- ## Exercise — Deploy Dockercoins - Deploy the dockercoins application to our Kubernetes cluster - Connect components together - Expose the web UI and open it in a web browser to check that it works .debug[[exercises/k8sfundamentals-brief.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/exercises/k8sfundamentals-brief.md)] --- ## Exercise — Local Cluster - Deploy a local Kubernetes cluster if you don't already have one - Deploy dockercoins on that cluster - Connect to the web UI in your browser - Scale up dockercoins .debug[[exercises/localcluster-brief.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/exercises/localcluster-brief.md)] --- ## Exercise — Healthchecks - Add readiness and liveness probes to a web service (we will use the `rng` service in the dockercoins app) - See what happens when the load increases (spoiler alert: it involves timeouts!) .debug[[exercises/healthchecks-brief.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/exercises/healthchecks-brief.md)] --- name: toc-part-1 ## Part 1 - [Our sample application](#toc-our-sample-application) - [Kubernetes concepts](#toc-kubernetes-concepts) - [First contact with `kubectl`](#toc-first-contact-with-kubectl) - [Running our first containers on Kubernetes](#toc-running-our-first-containers-on-kubernetes) - [Kubernetes network model](#toc-kubernetes-network-model) - [Exposing containers](#toc-exposing-containers) - [Shipping images with a registry](#toc-shipping-images-with-a-registry) - [Exercise — Deploy Dockercoins](#toc-exercise--deploy-dockercoins) - [Running our application on Kubernetes](#toc-running-our-application-on-kubernetes) .debug[(auto-generated TOC)] --- name: toc-part-2 ## Part 2 - [Labels and annotations](#toc-labels-and-annotations) - [Revisiting `kubectl logs`](#toc-revisiting-kubectl-logs) - [Accessing logs from the CLI](#toc-accessing-logs-from-the-cli) - [Namespaces](#toc-namespaces) - [Deploying with YAML](#toc-deploying-with-yaml) - [Declarative vs imperative](#toc-declarative-vs-imperative) - [Authoring YAML](#toc-authoring-yaml) - [Setting up Kubernetes](#toc-setting-up-kubernetes) - [Running a local development cluster](#toc-running-a-local-development-cluster) - [Controlling a Kubernetes cluster remotely](#toc-controlling-a-kubernetes-cluster-remotely) - [Accessing internal services](#toc-accessing-internal-services) - [Accessing the API with `kubectl proxy`](#toc-accessing-the-api-with-kubectl-proxy) - [Exercise — Local Cluster](#toc-exercise--local-cluster) .debug[(auto-generated TOC)] --- name: toc-part-3 ## Part 3 - [Scaling our demo app](#toc-scaling-our-demo-app) - [Daemon sets](#toc-daemon-sets) - [Labels and selectors](#toc-labels-and-selectors) - [Rolling updates](#toc-rolling-updates) - [Healthchecks](#toc-healthchecks) - [The Kubernetes dashboard](#toc-the-kubernetes-dashboard) - [Security implications of `kubectl apply`](#toc-security-implications-of-kubectl-apply) - [k9s](#toc-ks) - [Tilt](#toc-tilt) - [Exercise — Healthchecks](#toc-exercise--healthchecks) .debug[(auto-generated TOC)] --- name: toc-part-4 ## Part 4 - [Exposing HTTP services with Ingress resources](#toc-exposing-http-services-with-ingress-resources) - [Volumes](#toc-volumes) - [Managing configuration](#toc-managing-configuration) - [Managing secrets](#toc-managing-secrets) - [Managing stacks with Helm](#toc-managing-stacks-with-helm) - [Exercise — Ingress](#toc-exercise--ingress) .debug[(auto-generated TOC)] --- name: toc-part-5 ## Part 5 - [Authentication and authorization](#toc-authentication-and-authorization) - [Resource Limits](#toc-resource-limits) - [Defining min, max, and default resources](#toc-defining-min-max-and-default-resources) - [Namespace quotas](#toc-namespace-quotas) - [Limiting resources in practice](#toc-limiting-resources-in-practice) - [Checking Node and Pod resource usage](#toc-checking-node-and-pod-resource-usage) - [Cluster sizing](#toc-cluster-sizing) - [Executing batch jobs](#toc-executing-batch-jobs) .debug[(auto-generated TOC)] .debug[[shared/toc.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/toc.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-our-sample-application class: title Our sample application .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-1) | [Next part](#toc-kubernetes-concepts) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Our sample application - We will clone the GitHub repository onto our `node1` - The repository also contains scripts and tools that we will use through the workshop .lab[ <!-- ```bash cd ~ if [ -d container.training ]; then mv container.training container.training.$RANDOM fi ``` --> - Clone the repository on `node1`: ```bash git clone https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training ``` ] (You can also fork the repository on GitHub and clone your fork if you prefer that.) .debug[[shared/sampleapp.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/sampleapp.md)] --- ## Downloading and running the application Let's start this before we look around, as downloading will take a little time... .lab[ - Go to the `dockercoins` directory, in the cloned repository: ```bash cd ~/container.training/dockercoins ``` - Use Compose to build and run all containers: ```bash docker-compose up ``` <!-- ```longwait units of work done``` --> ] Compose tells Docker to build all container images (pulling the corresponding base images), then starts all containers, and displays aggregated logs. .debug[[shared/sampleapp.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/sampleapp.md)] --- ## What's this application? -- - It is a DockerCoin miner! 💰🐳📦🚢 -- - No, you can't buy coffee with DockerCoin -- - How dockercoins works: - generate a few random bytes - hash these bytes - increment a counter (to keep track of speed) - repeat forever! -- - DockerCoin is *not* a cryptocurrency (the only common points are "randomness," "hashing," and "coins" in the name) .debug[[shared/sampleapp.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/sampleapp.md)] --- ## DockerCoin in the microservices era - The dockercoins app is made of 5 services: - `rng` = web service generating random bytes - `hasher` = web service computing hash of POSTed data - `worker` = background process calling `rng` and `hasher` - `webui` = web interface to watch progress - `redis` = data store (holds a counter updated by `worker`) - These 5 services are visible in the application's Compose file, [docker-compose.yml]( https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/blob/master/dockercoins/docker-compose.yml) .debug[[shared/sampleapp.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/sampleapp.md)] --- ## How dockercoins works - `worker` invokes web service `rng` to generate random bytes - `worker` invokes web service `hasher` to hash these bytes - `worker` does this in an infinite loop - every second, `worker` updates `redis` to indicate how many loops were done - `webui` queries `redis`, and computes and exposes "hashing speed" in our browser *(See diagram on next slide!)* .debug[[shared/sampleapp.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/sampleapp.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[shared/sampleapp.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/sampleapp.md)] --- ## Service discovery in container-land How does each service find out the address of the other ones? -- - We do not hard-code IP addresses in the code - We do not hard-code FQDNs in the code, either - We just connect to a service name, and container-magic does the rest (And by container-magic, we mean "a crafty, dynamic, embedded DNS server") .debug[[shared/sampleapp.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/sampleapp.md)] --- ## Example in `worker/worker.py` ```python redis = Redis("`redis`") def get_random_bytes(): r = requests.get("http://`rng`/32") return r.content def hash_bytes(data): r = requests.post("http://`hasher`/", data=data, headers={"Content-Type": "application/octet-stream"}) ``` (Full source code available [here]( https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/blob/8279a3bce9398f7c1a53bdd95187c53eda4e6435/dockercoins/worker/worker.py#L17 )) .debug[[shared/sampleapp.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/sampleapp.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Links, naming, and service discovery - Containers can have network aliases (resolvable through DNS) - Compose file version 2+ makes each container reachable through its service name - Compose file version 1 required "links" sections to accomplish this - Network aliases are automatically namespaced - you can have multiple apps declaring and using a service named `database` - containers in the blue app will resolve `database` to the IP of the blue database - containers in the green app will resolve `database` to the IP of the green database .debug[[shared/sampleapp.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/sampleapp.md)] --- ## Show me the code! - You can check the GitHub repository with all the materials of this workshop: <br/>https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training - The application is in the [dockercoins]( https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/master/dockercoins) subdirectory - The Compose file ([docker-compose.yml]( https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/blob/master/dockercoins/docker-compose.yml)) lists all 5 services - `redis` is using an official image from the Docker Hub - `hasher`, `rng`, `worker`, `webui` are each built from a Dockerfile - Each service's Dockerfile and source code is in its own directory (`hasher` is in the [hasher](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/blob/master/dockercoins/hasher/) directory, `rng` is in the [rng](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/blob/master/dockercoins/rng/) directory, etc.) .debug[[shared/sampleapp.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/sampleapp.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Compose file format version *This is relevant only if you have used Compose before 2016...* - Compose 1.6 introduced support for a new Compose file format (aka "v2") - Services are no longer at the top level, but under a `services` section - There has to be a `version` key at the top level, with value `"2"` (as a string, not an integer) - Containers are placed on a dedicated network, making links unnecessary - There are other minor differences, but upgrade is easy and straightforward .debug[[shared/sampleapp.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/sampleapp.md)] --- ## Our application at work - On the left-hand side, the "rainbow strip" shows the container names - On the right-hand side, we see the output of our containers - We can see the `worker` service making requests to `rng` and `hasher` - For `rng` and `hasher`, we see HTTP access logs .debug[[shared/sampleapp.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/sampleapp.md)] --- ## Connecting to the web UI - "Logs are exciting and fun!" (No-one, ever) - The `webui` container exposes a web dashboard; let's view it .lab[ - With a web browser, connect to `node1` on port 8000 - Remember: the `nodeX` aliases are valid only on the nodes themselves - In your browser, you need to enter the IP address of your node <!-- ```open http://node1:8000``` --> ] A drawing area should show up, and after a few seconds, a blue graph will appear. .debug[[shared/sampleapp.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/sampleapp.md)] --- class: self-paced, extra-details ## If the graph doesn't load If you just see a `Page not found` error, it might be because your Docker Engine is running on a different machine. This can be the case if: - you are using the Docker Toolbox - you are using a VM (local or remote) created with Docker Machine - you are controlling a remote Docker Engine When you run DockerCoins in development mode, the web UI static files are mapped to the container using a volume. Alas, volumes can only work on a local environment, or when using Docker Desktop for Mac or Windows. How to fix this? Stop the app with `^C`, edit `dockercoins.yml`, comment out the `volumes` section, and try again. .debug[[shared/sampleapp.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/sampleapp.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Why does the speed seem irregular? - It *looks like* the speed is approximately 4 hashes/second - Or more precisely: 4 hashes/second, with regular dips down to zero - Why? -- class: extra-details - The app actually has a constant, steady speed: 3.33 hashes/second <br/> (which corresponds to 1 hash every 0.3 seconds, for *reasons*) - Yes, and? .debug[[shared/sampleapp.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/sampleapp.md)] --- class: extra-details ## The reason why this graph is *not awesome* - The worker doesn't update the counter after every loop, but up to once per second - The speed is computed by the browser, checking the counter about once per second - Between two consecutive updates, the counter will increase either by 4, or by 0 - The perceived speed will therefore be 4 - 4 - 4 - 0 - 4 - 4 - 0 etc. - What can we conclude from this? -- class: extra-details - "I'm clearly incapable of writing good frontend code!" 😀 — Jérôme .debug[[shared/sampleapp.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/sampleapp.md)] --- ## Stopping the application - If we interrupt Compose (with `^C`), it will politely ask the Docker Engine to stop the app - The Docker Engine will send a `TERM` signal to the containers - If the containers do not exit in a timely manner, the Engine sends a `KILL` signal .lab[ - Stop the application by hitting `^C` <!-- ```key ^C``` --> ] -- Some containers exit immediately, others take longer. The containers that do not handle `SIGTERM` end up being killed after a 10s timeout. If we are very impatient, we can hit `^C` a second time! .debug[[shared/sampleapp.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/sampleapp.md)] --- ## Clean up - Before moving on, let's remove those containers .lab[ - Tell Compose to remove everything: ```bash docker-compose down ``` ] .debug[[shared/composedown.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/composedown.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-kubernetes-concepts class: title Kubernetes concepts .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-our-sample-application) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-1) | [Next part](#toc-first-contact-with-kubectl) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Kubernetes concepts - Kubernetes is a container management system - It runs and manages containerized applications on a cluster -- - What does that really mean? .debug[[k8s/concepts-k8s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/concepts-k8s.md)] --- ## What can we do with Kubernetes? - Let's imagine that we have a 3-tier e-commerce app: - web frontend - API backend - database (that we will keep out of Kubernetes for now) - We have built images for our frontend and backend components (e.g. with Dockerfiles and `docker build`) - We are running them successfully with a local environment (e.g. with Docker Compose) - Let's see how we would deploy our app on Kubernetes! .debug[[k8s/concepts-k8s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/concepts-k8s.md)] --- ## Basic things we can ask Kubernetes to do -- - Start 5 containers using image `atseashop/api:v1.3` -- - Place an internal load balancer in front of these containers -- - Start 10 containers using image `atseashop/webfront:v1.3` -- - Place a public load balancer in front of these containers -- - It's Black Friday (or Christmas), traffic spikes, grow our cluster and add containers -- - New release! Replace my containers with the new image `atseashop/webfront:v1.4` -- - Keep processing requests during the upgrade; update my containers one at a time .debug[[k8s/concepts-k8s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/concepts-k8s.md)] --- ## Other things that Kubernetes can do for us - Autoscaling (straightforward on CPU; more complex on other metrics) - Resource management and scheduling (reserve CPU/RAM for containers; placement constraints) - Advanced rollout patterns (blue/green deployment, canary deployment) .debug[[k8s/concepts-k8s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/concepts-k8s.md)] --- ## More things that Kubernetes can do for us - Batch jobs (one-off; parallel; also cron-style periodic execution) - Fine-grained access control (defining *what* can be done by *whom* on *which* resources) - Stateful services (databases, message queues, etc.) - Automating complex tasks with *operators* (e.g. database replication, failover, etc.) .debug[[k8s/concepts-k8s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/concepts-k8s.md)] --- ## Kubernetes architecture .debug[[k8s/concepts-k8s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/concepts-k8s.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/concepts-k8s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/concepts-k8s.md)] --- ## Kubernetes architecture - Ha ha ha ha - OK, I was trying to scare you, it's much simpler than that ❤️ .debug[[k8s/concepts-k8s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/concepts-k8s.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/concepts-k8s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/concepts-k8s.md)] --- ## Credits - The first schema is a Kubernetes cluster with storage backed by multi-path iSCSI (Courtesy of [Yongbok Kim](https://www.yongbok.net/blog/)) - The second one is a simplified representation of a Kubernetes cluster (Courtesy of [Imesh Gunaratne](https://medium.com/containermind/a-reference-architecture-for-deploying-wso2-middleware-on-kubernetes-d4dee7601e8e)) .debug[[k8s/concepts-k8s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/concepts-k8s.md)] --- ## Kubernetes architecture: the nodes - The nodes executing our containers run a collection of services: - a container Engine (typically Docker) - kubelet (the "node agent") - kube-proxy (a necessary but not sufficient network component) - Nodes were formerly called "minions" (You might see that word in older articles or documentation) .debug[[k8s/concepts-k8s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/concepts-k8s.md)] --- ## Kubernetes architecture: the control plane - The Kubernetes logic (its "brains") is a collection of services: - the API server (our point of entry to everything!) - core services like the scheduler and controller manager - `etcd` (a highly available key/value store; the "database" of Kubernetes) - Together, these services form the control plane of our cluster - The control plane is also called the "master" .debug[[k8s/concepts-k8s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/concepts-k8s.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/concepts-k8s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/concepts-k8s.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Running the control plane on special nodes - It is common to reserve a dedicated node for the control plane (Except for single-node development clusters, like when using minikube) - This node is then called a "master" (Yes, this is ambiguous: is the "master" a node, or the whole control plane?) - Normal applications are restricted from running on this node (By using a mechanism called ["taints"](https://kubernetes.io/docs/concepts/configuration/taint-and-toleration/)) - When high availability is required, each service of the control plane must be resilient - The control plane is then replicated on multiple nodes (This is sometimes called a "multi-master" setup) .debug[[k8s/concepts-k8s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/concepts-k8s.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Running the control plane outside containers - The services of the control plane can run in or out of containers - For instance: since `etcd` is a critical service, some people deploy it directly on a dedicated cluster (without containers) (This is illustrated on the first "super complicated" schema) - In some hosted Kubernetes offerings (e.g. AKS, GKE, EKS), the control plane is invisible (We only "see" a Kubernetes API endpoint) - In that case, there is no "master node" *For this reason, it is more accurate to say "control plane" rather than "master."* .debug[[k8s/concepts-k8s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/concepts-k8s.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/concepts-k8s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/concepts-k8s.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/concepts-k8s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/concepts-k8s.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/concepts-k8s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/concepts-k8s.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/concepts-k8s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/concepts-k8s.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/concepts-k8s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/concepts-k8s.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/concepts-k8s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/concepts-k8s.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/concepts-k8s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/concepts-k8s.md)] --- class: extra-details ## How many nodes should a cluster have? - There is no particular constraint (no need to have an odd number of nodes for quorum) - A cluster can have zero node (but then it won't be able to start any pods) - For testing and development, having a single node is fine - For production, make sure that you have extra capacity (so that your workload still fits if you lose a node or a group of nodes) - Kubernetes is tested with [up to 5000 nodes](https://kubernetes.io/docs/setup/best-practices/cluster-large/) (however, running a cluster of that size requires a lot of tuning) .debug[[k8s/concepts-k8s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/concepts-k8s.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Do we need to run Docker at all? No! -- - The Docker Engine used to be the default option to run containers with Kubernetes - Support for Docker (specifically: dockershim) was removed in Kubernetes 1.24 - We can leverage other pluggable runtimes through the *Container Runtime Interface* - <del>We could also use `rkt` ("Rocket") from CoreOS</del> (deprecated) .debug[[k8s/concepts-k8s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/concepts-k8s.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Some runtimes available through CRI - [containerd](https://github.com/containerd/containerd/blob/master/README.md) - maintained by Docker, IBM, and community - used by Docker Engine, microk8s, k3s, GKE; also standalone - comes with its own CLI, `ctr` - [CRI-O](https://github.com/cri-o/cri-o/blob/master/README.md): - maintained by Red Hat, SUSE, and community - used by OpenShift and Kubic - designed specifically as a minimal runtime for Kubernetes - [And more](https://kubernetes.io/docs/setup/production-environment/container-runtimes/) .debug[[k8s/concepts-k8s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/concepts-k8s.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Do we need to run Docker at all? Yes! -- - In this workshop, we run our app on a single node first - We will need to build images and ship them around - We can do these things without Docker <br/> (but with some languages/frameworks, it might be much harder) - Docker is still the most stable container engine today <br/> (but other options are maturing very quickly) .debug[[k8s/concepts-k8s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/concepts-k8s.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Do we need to run Docker at all? - On our Kubernetes clusters: *Not anymore* - On our development environments, CI pipelines ... : *Yes, almost certainly* .debug[[k8s/concepts-k8s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/concepts-k8s.md)] --- ## Interacting with Kubernetes - We will interact with our Kubernetes cluster through the Kubernetes API - The Kubernetes API is (mostly) RESTful - It allows us to create, read, update, delete *resources* - A few common resource types are: - node (a machine — physical or virtual — in our cluster) - pod (group of containers running together on a node) - service (stable network endpoint to connect to one or multiple containers) .debug[[k8s/concepts-k8s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/concepts-k8s.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/concepts-k8s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/concepts-k8s.md)] --- ## Scaling - How would we scale the pod shown on the previous slide? - **Do** create additional pods - each pod can be on a different node - each pod will have its own IP address - **Do not** add more NGINX containers in the pod - all the NGINX containers would be on the same node - they would all have the same IP address <br/>(resulting in `Address alreading in use` errors) .debug[[k8s/concepts-k8s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/concepts-k8s.md)] --- ## Together or separate - Should we put e.g. a web application server and a cache together? <br/> ("cache" being something like e.g. Memcached or Redis) - Putting them **in the same pod** means: - they have to be scaled together - they can communicate very efficiently over `localhost` - Putting them **in different pods** means: - they can be scaled separately - they must communicate over remote IP addresses <br/>(incurring more latency, lower performance) - Both scenarios can make sense, depending on our goals .debug[[k8s/concepts-k8s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/concepts-k8s.md)] --- ## Credits - The first diagram is courtesy of Lucas Käldström, in [this presentation](https://speakerdeck.com/luxas/kubeadm-cluster-creation-internals-from-self-hosting-to-upgradability-and-ha) - it's one of the best Kubernetes architecture diagrams available! - The second diagram is courtesy of Weave Works - a *pod* can have multiple containers working together - IP addresses are associated with *pods*, not with individual containers Both diagrams used with permission. ??? :EN:- Kubernetes concepts :FR:- Kubernetes en théorie .debug[[k8s/concepts-k8s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/concepts-k8s.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-first-contact-with-kubectl class: title First contact with `kubectl` .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-kubernetes-concepts) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-1) | [Next part](#toc-running-our-first-containers-on-kubernetes) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # First contact with `kubectl` - `kubectl` is (almost) the only tool we'll need to talk to Kubernetes - It is a rich CLI tool around the Kubernetes API (Everything you can do with `kubectl`, you can do directly with the API) - On our machines, there is a `~/.kube/config` file with: - the Kubernetes API address - the path to our TLS certificates used to authenticate - You can also use the `--kubeconfig` flag to pass a config file - Or directly `--server`, `--user`, etc. - `kubectl` can be pronounced "Cube C T L", "Cube cuttle", "Cube cuddle"... .debug[[k8s/kubectlget.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlget.md)] --- class: extra-details ## `kubectl` is the new SSH - We often start managing servers with SSH (installing packages, troubleshooting ...) - At scale, it becomes tedious, repetitive, error-prone - Instead, we use config management, central logging, etc. - In many cases, we still need SSH: - as the underlying access method (e.g. Ansible) - to debug tricky scenarios - to inspect and poke at things .debug[[k8s/kubectlget.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlget.md)] --- class: extra-details ## The parallel with `kubectl` - We often start managing Kubernetes clusters with `kubectl` (deploying applications, troubleshooting ...) - At scale (with many applications or clusters), it becomes tedious, repetitive, error-prone - Instead, we use automated pipelines, observability tooling, etc. - In many cases, we still need `kubectl`: - to debug tricky scenarios - to inspect and poke at things - The Kubernetes API is always the underlying access method .debug[[k8s/kubectlget.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlget.md)] --- ## `kubectl get` - Let's look at our `Node` resources with `kubectl get`! .lab[ - Look at the composition of our cluster: ```bash kubectl get node ``` - These commands are equivalent: ```bash kubectl get no kubectl get node kubectl get nodes ``` ] .debug[[k8s/kubectlget.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlget.md)] --- ## Obtaining machine-readable output - `kubectl get` can output JSON, YAML, or be directly formatted .lab[ - Give us more info about the nodes: ```bash kubectl get nodes -o wide ``` - Let's have some YAML: ```bash kubectl get no -o yaml ``` See that `kind: List` at the end? It's the type of our result! ] .debug[[k8s/kubectlget.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlget.md)] --- ## (Ab)using `kubectl` and `jq` - It's super easy to build custom reports .lab[ - Show the capacity of all our nodes as a stream of JSON objects: ```bash kubectl get nodes -o json | jq ".items[] | {name:.metadata.name} + .status.capacity" ``` ] .debug[[k8s/kubectlget.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlget.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Exploring types and definitions - We can list all available resource types by running `kubectl api-resources` <br/> (In Kubernetes 1.10 and prior, this command used to be `kubectl get`) - We can view the definition for a resource type with: ```bash kubectl explain type ``` - We can view the definition of a field in a resource, for instance: ```bash kubectl explain node.spec ``` - Or get the full definition of all fields and sub-fields: ```bash kubectl explain node --recursive ``` .debug[[k8s/kubectlget.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlget.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Introspection vs. documentation - We can access the same information by reading the [API documentation](https://kubernetes.io/docs/reference/#api-reference) - The API documentation is usually easier to read, but: - it won't show custom types (like Custom Resource Definitions) - we need to make sure that we look at the correct version - `kubectl api-resources` and `kubectl explain` perform *introspection* (they communicate with the API server and obtain the exact type definitions) .debug[[k8s/kubectlget.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlget.md)] --- ## Type names - The most common resource names have three forms: - singular (e.g. `node`, `service`, `deployment`) - plural (e.g. `nodes`, `services`, `deployments`) - short (e.g. `no`, `svc`, `deploy`) - Some resources do not have a short name - `Endpoints` only have a plural form (because even a single `Endpoints` resource is actually a list of endpoints) .debug[[k8s/kubectlget.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlget.md)] --- ## Viewing details - We can use `kubectl get -o yaml` to see all available details - However, YAML output is often simultaneously too much and not enough - For instance, `kubectl get node node1 -o yaml` is: - too much information (e.g.: list of images available on this node) - not enough information (e.g.: doesn't show pods running on this node) - difficult to read for a human operator - For a comprehensive overview, we can use `kubectl describe` instead .debug[[k8s/kubectlget.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlget.md)] --- ## `kubectl describe` - `kubectl describe` needs a resource type and (optionally) a resource name - It is possible to provide a resource name *prefix* (all matching objects will be displayed) - `kubectl describe` will retrieve some extra information about the resource .lab[ - Look at the information available for `node1` with one of the following commands: ```bash kubectl describe node/node1 kubectl describe node node1 ``` ] (We should notice a bunch of control plane pods.) .debug[[k8s/kubectlget.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlget.md)] --- ## Listing running containers - Containers are manipulated through *pods* - A pod is a group of containers: - running together (on the same node) - sharing resources (RAM, CPU; but also network, volumes) .lab[ - List pods on our cluster: ```bash kubectl get pods ``` ] -- *Where are the pods that we saw just a moment earlier?!?* .debug[[k8s/kubectlget.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlget.md)] --- ## Namespaces - Namespaces allow us to segregate resources .lab[ - List the namespaces on our cluster with one of these commands: ```bash kubectl get namespaces kubectl get namespace kubectl get ns ``` ] -- *You know what ... This `kube-system` thing looks suspicious.* *In fact, I'm pretty sure it showed up earlier, when we did:* `kubectl describe node node1` .debug[[k8s/kubectlget.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlget.md)] --- ## Accessing namespaces - By default, `kubectl` uses the `default` namespace - We can see resources in all namespaces with `--all-namespaces` .lab[ - List the pods in all namespaces: ```bash kubectl get pods --all-namespaces ``` - Since Kubernetes 1.14, we can also use `-A` as a shorter version: ```bash kubectl get pods -A ``` ] *Here are our system pods!* .debug[[k8s/kubectlget.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlget.md)] --- ## What are all these control plane pods? - `etcd` is our etcd server - `kube-apiserver` is the API server - `kube-controller-manager` and `kube-scheduler` are other control plane components - `coredns` provides DNS-based service discovery ([replacing kube-dns as of 1.11](https://kubernetes.io/blog/2018/07/10/coredns-ga-for-kubernetes-cluster-dns/)) - `kube-proxy` is the (per-node) component managing port mappings and such - `weave` is the (per-node) component managing the network overlay - the `READY` column indicates the number of containers in each pod (1 for most pods, but `weave` has 2, for instance) .debug[[k8s/kubectlget.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlget.md)] --- ## Scoping another namespace - We can also look at a different namespace (other than `default`) .lab[ - List only the pods in the `kube-system` namespace: ```bash kubectl get pods --namespace=kube-system kubectl get pods -n kube-system ``` ] .debug[[k8s/kubectlget.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlget.md)] --- ## Namespaces and other `kubectl` commands - We can use `-n`/`--namespace` with almost every `kubectl` command - Example: - `kubectl create --namespace=X` to create something in namespace X - We can use `-A`/`--all-namespaces` with most commands that manipulate multiple objects - Examples: - `kubectl delete` can delete resources across multiple namespaces - `kubectl label` can add/remove/update labels across multiple namespaces .debug[[k8s/kubectlget.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlget.md)] --- class: extra-details ## What about `kube-public`? .lab[ - List the pods in the `kube-public` namespace: ```bash kubectl -n kube-public get pods ``` ] Nothing! `kube-public` is created by kubeadm & [used for security bootstrapping](https://kubernetes.io/blog/2017/01/stronger-foundation-for-creating-and-managing-kubernetes-clusters). .debug[[k8s/kubectlget.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlget.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Exploring `kube-public` - The only interesting object in `kube-public` is a ConfigMap named `cluster-info` .lab[ - List ConfigMap objects: ```bash kubectl -n kube-public get configmaps ``` - Inspect `cluster-info`: ```bash kubectl -n kube-public get configmap cluster-info -o yaml ``` ] Note the `selfLink` URI: `/api/v1/namespaces/kube-public/configmaps/cluster-info` We can use that! .debug[[k8s/kubectlget.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlget.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Accessing `cluster-info` - Earlier, when trying to access the API server, we got a `Forbidden` message - But `cluster-info` is readable by everyone (even without authentication) .lab[ - Retrieve `cluster-info`: ```bash curl -k https://10.96.0.1/api/v1/namespaces/kube-public/configmaps/cluster-info ``` ] - We were able to access `cluster-info` (without auth) - It contains a `kubeconfig` file .debug[[k8s/kubectlget.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlget.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Retrieving `kubeconfig` - We can easily extract the `kubeconfig` file from this ConfigMap .lab[ - Display the content of `kubeconfig`: ```bash curl -sk https://10.96.0.1/api/v1/namespaces/kube-public/configmaps/cluster-info \ | jq -r .data.kubeconfig ``` ] - This file holds the canonical address of the API server, and the public key of the CA - This file *does not* hold client keys or tokens - This is not sensitive information, but allows us to establish trust .debug[[k8s/kubectlget.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlget.md)] --- class: extra-details ## What about `kube-node-lease`? - Starting with Kubernetes 1.14, there is a `kube-node-lease` namespace (or in Kubernetes 1.13 if the NodeLease feature gate is enabled) - That namespace contains one Lease object per node - *Node leases* are a new way to implement node heartbeats (i.e. node regularly pinging the control plane to say "I'm alive!") - For more details, see [Efficient Node Heartbeats KEP] or the [node controller documentation] [Efficient Node Heartbeats KEP]: https://github.com/kubernetes/enhancements/blob/master/keps/sig-node/589-efficient-node-heartbeats/README.md [node controller documentation]: https://kubernetes.io/docs/concepts/architecture/nodes/#node-controller .debug[[k8s/kubectlget.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlget.md)] --- ## Services - A *service* is a stable endpoint to connect to "something" (In the initial proposal, they were called "portals") .lab[ - List the services on our cluster with one of these commands: ```bash kubectl get services kubectl get svc ``` ] -- There is already one service on our cluster: the Kubernetes API itself. .debug[[k8s/kubectlget.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlget.md)] --- ## ClusterIP services - A `ClusterIP` service is internal, available from the cluster only - This is useful for introspection from within containers .lab[ - Try to connect to the API: ```bash curl -k https://`10.96.0.1` ``` - `-k` is used to skip certificate verification - Make sure to replace 10.96.0.1 with the CLUSTER-IP shown by `kubectl get svc` ] The command above should either time out, or show an authentication error. Why? .debug[[k8s/kubectlget.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlget.md)] --- ## Time out - Connections to ClusterIP services only work *from within the cluster* - If we are outside the cluster, the `curl` command will probably time out (Because the IP address, e.g. 10.96.0.1, isn't routed properly outside the cluster) - This is the case with most "real" Kubernetes clusters - To try the connection from within the cluster, we can use [shpod](https://github.com/jpetazzo/shpod) .debug[[k8s/kubectlget.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlget.md)] --- ## Authentication error This is what we should see when connecting from within the cluster: ```json $ curl -k https://10.96.0.1 { "kind": "Status", "apiVersion": "v1", "metadata": { }, "status": "Failure", "message": "forbidden: User \"system:anonymous\" cannot get path \"/\"", "reason": "Forbidden", "details": { }, "code": 403 } ``` .debug[[k8s/kubectlget.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlget.md)] --- ## Explanations - We can see `kind`, `apiVersion`, `metadata` - These are typical of a Kubernetes API reply - Because we *are* talking to the Kubernetes API - The Kubernetes API tells us "Forbidden" (because it requires authentication) - The Kubernetes API is reachable from within the cluster (many apps integrating with Kubernetes will use this) .debug[[k8s/kubectlget.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlget.md)] --- ## DNS integration - Each service also gets a DNS record - The Kubernetes DNS resolver is available *from within pods* (and sometimes, from within nodes, depending on configuration) - Code running in pods can connect to services using their name (e.g. https://kubernetes/...) ??? :EN:- Getting started with kubectl :FR:- Se familiariser avec kubectl .debug[[k8s/kubectlget.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlget.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-running-our-first-containers-on-kubernetes class: title Running our first containers on Kubernetes .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-first-contact-with-kubectl) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-1) | [Next part](#toc-kubernetes-network-model) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Running our first containers on Kubernetes - First things first: we cannot run a container -- - We are going to run a pod, and in that pod there will be a single container -- - In that container in the pod, we are going to run a simple `ping` command .debug[[k8s/kubectl-run.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectl-run.md)] --- class: extra-details ## If you're running Kubernetes 1.17 (or older)... - This material assumes that you're running a recent version of Kubernetes (at least 1.19) <!-- ##VERSION## --> - You can check your version number with `kubectl version` (look at the server part) - In Kubernetes 1.17 and older, `kubectl run` creates a Deployment - If you're running such an old version: - it's obsolete and no longer maintained - Kubernetes 1.17 is [EOL since January 2021][nonactive] - **upgrade NOW!** [nonactive]: https://kubernetes.io/releases/patch-releases/#non-active-branch-history .debug[[k8s/kubectl-run.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectl-run.md)] --- ## Starting a simple pod with `kubectl run` - `kubectl run` is convenient to start a single pod - We need to specify at least a *name* and the image we want to use - Optionally, we can specify the command to run in the pod .lab[ - Let's ping the address of `localhost`, the loopback interface: ```bash kubectl run pingpong --image alpine ping 127.0.0.1 ``` <!-- ```hide kubectl wait pod --selector=run=pingpong --for condition=ready``` --> ] The output tells us that a Pod was created: ``` pod/pingpong created ``` .debug[[k8s/kubectl-run.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectl-run.md)] --- ## Viewing container output - Let's use the `kubectl logs` command - It takes a Pod name as argument - Unless specified otherwise, it will only show logs of the first container in the pod (Good thing there's only one in ours!) .lab[ - View the result of our `ping` command: ```bash kubectl logs pingpong ``` ] .debug[[k8s/kubectl-run.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectl-run.md)] --- ## Streaming logs in real time - Just like `docker logs`, `kubectl logs` supports convenient options: - `-f`/`--follow` to stream logs in real time (à la `tail -f`) - `--tail` to indicate how many lines you want to see (from the end) - `--since` to get logs only after a given timestamp .lab[ - View the latest logs of our `ping` command: ```bash kubectl logs pingpong --tail 1 --follow ``` - Stop it with Ctrl-C <!-- ```wait seq=3``` ```keys ^C``` --> ] .debug[[k8s/kubectl-run.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectl-run.md)] --- ## Scaling our application - `kubectl` gives us a simple command to scale a workload: `kubectl scale TYPE NAME --replicas=HOWMANY` - Let's try it on our Pod, so that we have more Pods! .lab[ - Try to scale the Pod: ```bash kubectl scale pod pingpong --replicas=3 ``` ] 🤔 We get the following error, what does that mean? ``` Error from server (NotFound): the server could not find the requested resource ``` .debug[[k8s/kubectl-run.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectl-run.md)] --- ## Scaling a Pod - We cannot "scale a Pod" (that's not completely true; we could give it more CPU/RAM) - If we want more Pods, we need to create more Pods (i.e. execute `kubectl run` multiple times) - There must be a better way! (spoiler alert: yes, there is a better way!) .debug[[k8s/kubectl-run.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectl-run.md)] --- class: extra-details ## `NotFound` - What's the meaning of that error? ``` Error from server (NotFound): the server could not find the requested resource ``` - When we execute `kubectl scale THAT-RESOURCE --replicas=THAT-MANY`, <br/> it is like telling Kubernetes: *go to THAT-RESOURCE and set the scaling button to position THAT-MANY* - Pods do not have a "scaling button" - Try to execute the `kubectl scale pod` command with `-v6` - We see a `PATCH` request to `/scale`: that's the "scaling button" (technically it's called a *subresource* of the Pod) .debug[[k8s/kubectl-run.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectl-run.md)] --- ## Creating more pods - We are going to create a ReplicaSet (= set of replicas = set of identical pods) - In fact, we will create a Deployment, which itself will create a ReplicaSet - Why so many layers? We'll explain that shortly, don't worry! .debug[[k8s/kubectl-run.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectl-run.md)] --- ## Creating a Deployment running `ping` - Let's create a Deployment instead of a single Pod .lab[ - Create the Deployment; pay attention to the `--`: ```bash kubectl create deployment pingpong --image=alpine -- ping 127.0.0.1 ``` ] - The `--` is used to separate: - "options/flags of `kubectl create` - command to run in the container .debug[[k8s/kubectl-run.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectl-run.md)] --- ## What has been created? .lab[ <!-- ```hide kubectl wait pod --selector=app=pingpong --for condition=ready ``` --> - Check the resources that were created: ```bash kubectl get all ``` ] Note: `kubectl get all` is a lie. It doesn't show everything. (But it shows a lot of "usual suspects", i.e. commonly used resources.) .debug[[k8s/kubectl-run.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectl-run.md)] --- ## There's a lot going on here! ``` NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE pod/pingpong 1/1 Running 0 4m17s pod/pingpong-6ccbc77f68-kmgfn 1/1 Running 0 11s NAME TYPE CLUSTER-IP EXTERNAL-IP PORT(S) AGE service/kubernetes ClusterIP 10.96.0.1 <none> 443/TCP 3h45 NAME READY UP-TO-DATE AVAILABLE AGE deployment.apps/pingpong 1/1 1 1 11s NAME DESIRED CURRENT READY AGE replicaset.apps/pingpong-6ccbc77f68 1 1 1 11s ``` Our new Pod is not named `pingpong`, but `pingpong-xxxxxxxxxxx-yyyyy`. We have a Deployment named `pingpong`, and an extra ReplicaSet, too. What's going on? .debug[[k8s/kubectl-run.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectl-run.md)] --- ## From Deployment to Pod We have the following resources: - `deployment.apps/pingpong` This is the Deployment that we just created. - `replicaset.apps/pingpong-xxxxxxxxxx` This is a Replica Set created by this Deployment. - `pod/pingpong-xxxxxxxxxx-yyyyy` This is a *pod* created by the Replica Set. Let's explain what these things are. .debug[[k8s/kubectl-run.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectl-run.md)] --- ## Pod - Can have one or multiple containers - Runs on a single node (Pod cannot "straddle" multiple nodes) - Pods cannot be moved (e.g. in case of node outage) - Pods cannot be scaled horizontally (except by manually creating more Pods) .debug[[k8s/kubectl-run.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectl-run.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Pod details - A Pod is not a process; it's an environment for containers - it cannot be "restarted" - it cannot "crash" - The containers in a Pod can crash - They may or may not get restarted (depending on Pod's restart policy) - If all containers exit successfully, the Pod ends in "Succeeded" phase - If some containers fail and don't get restarted, the Pod ends in "Failed" phase .debug[[k8s/kubectl-run.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectl-run.md)] --- ## Replica Set - Set of identical (replicated) Pods - Defined by a pod template + number of desired replicas - If there are not enough Pods, the Replica Set creates more (e.g. in case of node outage; or simply when scaling up) - If there are too many Pods, the Replica Set deletes some (e.g. if a node was disconnected and comes back; or when scaling down) - We can scale up/down a Replica Set - we update the manifest of the Replica Set - as a consequence, the Replica Set controller creates/deletes Pods .debug[[k8s/kubectl-run.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectl-run.md)] --- ## Deployment - Replica Sets control *identical* Pods - Deployments are used to roll out different Pods (different image, command, environment variables, ...) - When we update a Deployment with a new Pod definition: - a new Replica Set is created with the new Pod definition - that new Replica Set is progressively scaled up - meanwhile, the old Replica Set(s) is(are) scaled down - This is a *rolling update*, minimizing application downtime - When we scale up/down a Deployment, it scales up/down its Replica Set .debug[[k8s/kubectl-run.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectl-run.md)] --- ## Can we scale now? - Let's try `kubectl scale` again, but on the Deployment! .lab[ - Scale our `pingpong` deployment: ```bash kubectl scale deployment pingpong --replicas 3 ``` - Note that we could also write it like this: ```bash kubectl scale deployment/pingpong --replicas 3 ``` - Check that we now have multiple pods: ```bash kubectl get pods ``` ] .debug[[k8s/kubectl-run.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectl-run.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Scaling a Replica Set - What if we scale the Replica Set instead of the Deployment? - The Deployment would notice it right away and scale back to the initial level - The Replica Set makes sure that we have the right numbers of Pods - The Deployment makes sure that the Replica Set has the right size (conceptually, it delegates the management of the Pods to the Replica Set) - This might seem weird (why this extra layer?) but will soon make sense (when we will look at how rolling updates work!) .debug[[k8s/kubectl-run.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectl-run.md)] --- ## Checking Deployment logs - `kubectl logs` needs a Pod name - But it can also work with a *type/name* (e.g. `deployment/pingpong`) .lab[ - View the result of our `ping` command: ```bash kubectl logs deploy/pingpong --tail 2 ``` ] - It shows us the logs of the first Pod of the Deployment - We'll see later how to get the logs of *all* the Pods! .debug[[k8s/kubectl-run.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectl-run.md)] --- ## Resilience - The *deployment* `pingpong` watches its *replica set* - The *replica set* ensures that the right number of *pods* are running - What happens if pods disappear? .lab[ - In a separate window, watch the list of pods: ```bash watch kubectl get pods ``` <!-- ```wait Every 2.0s``` ```tmux split-pane -v``` --> - Destroy the pod currently shown by `kubectl logs`: ``` kubectl delete pod pingpong-xxxxxxxxxx-yyyyy ``` <!-- ```tmux select-pane -t 0``` ```copy pingpong-[^-]*-.....``` ```tmux last-pane``` ```keys kubectl delete pod ``` ```paste``` ```key ^J``` ```check``` --> ] .debug[[k8s/kubectl-run.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectl-run.md)] --- ## What happened? - `kubectl delete pod` terminates the pod gracefully (sending it the TERM signal and waiting for it to shutdown) - As soon as the pod is in "Terminating" state, the Replica Set replaces it - But we can still see the output of the "Terminating" pod in `kubectl logs` - Until 30 seconds later, when the grace period expires - The pod is then killed, and `kubectl logs` exits .debug[[k8s/kubectl-run.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectl-run.md)] --- ## Deleting a standalone Pod - What happens if we delete a standalone Pod? (like the first `pingpong` Pod that we created) .lab[ - Delete the Pod: ```bash kubectl delete pod pingpong ``` <!-- ```key ^D``` ```key ^C``` --> ] - No replacement Pod gets created because there is no *controller* watching it - That's why we will rarely use standalone Pods in practice (except for e.g. punctual debugging or executing a short supervised task) ??? :EN:- Running pods and deployments :FR:- Créer un pod et un déploiement .debug[[k8s/kubectl-run.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectl-run.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-kubernetes-network-model class: title Kubernetes network model .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-running-our-first-containers-on-kubernetes) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-1) | [Next part](#toc-exposing-containers) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Kubernetes network model - TL,DR: *Our cluster (nodes and pods) is one big flat IP network.* -- - In detail: - all nodes must be able to reach each other, without NAT - all pods must be able to reach each other, without NAT - pods and nodes must be able to reach each other, without NAT - each pod is aware of its IP address (no NAT) - pod IP addresses are assigned by the network implementation - Kubernetes doesn't mandate any particular implementation .debug[[k8s/kubenet.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubenet.md)] --- ## Kubernetes network model: the good - Everything can reach everything - No address translation - No port translation - No new protocol - The network implementation can decide how to allocate addresses - IP addresses don't have to be "portable" from a node to another (We can use e.g. a subnet per node and use a simple routed topology) - The specification is simple enough to allow many various implementations .debug[[k8s/kubenet.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubenet.md)] --- ## Kubernetes network model: the less good - Everything can reach everything - if you want security, you need to add network policies - the network implementation that you use needs to support them - There are literally dozens of implementations out there (https://github.com/containernetworking/cni/ lists more than 25 plugins) - Pods have level 3 (IP) connectivity, but *services* are level 4 (TCP or UDP) (Services map to a single UDP or TCP port; no port ranges or arbitrary IP packets) - `kube-proxy` is on the data path when connecting to a pod or container, <br/>and it's not particularly fast (relies on userland proxying or iptables) .debug[[k8s/kubenet.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubenet.md)] --- ## Kubernetes network model: in practice - The nodes that we are using have been set up to use [Weave](https://github.com/weaveworks/weave) - We don't endorse Weave in a particular way, it just Works For Us - Don't worry about the warning about `kube-proxy` performance - Unless you: - routinely saturate 10G network interfaces - count packet rates in millions per second - run high-traffic VOIP or gaming platforms - do weird things that involve millions of simultaneous connections <br/>(in which case you're already familiar with kernel tuning) - If necessary, there are alternatives to `kube-proxy`; e.g. [`kube-router`](https://www.kube-router.io) .debug[[k8s/kubenet.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubenet.md)] --- class: extra-details ## The Container Network Interface (CNI) - Most Kubernetes clusters use CNI "plugins" to implement networking - When a pod is created, Kubernetes delegates the network setup to these plugins (it can be a single plugin, or a combination of plugins, each doing one task) - Typically, CNI plugins will: - allocate an IP address (by calling an IPAM plugin) - add a network interface into the pod's network namespace - configure the interface as well as required routes etc. .debug[[k8s/kubenet.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubenet.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Multiple moving parts - The "pod-to-pod network" or "pod network": - provides communication between pods and nodes - is generally implemented with CNI plugins - The "pod-to-service network": - provides internal communication and load balancing - is generally implemented with kube-proxy (or e.g. kube-router) - Network policies: - provide firewalling and isolation - can be bundled with the "pod network" or provided by another component .debug[[k8s/kubenet.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubenet.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/kubenet.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubenet.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/kubenet.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubenet.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/kubenet.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubenet.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/kubenet.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubenet.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/kubenet.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubenet.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Even more moving parts - Inbound traffic can be handled by multiple components: - something like kube-proxy or kube-router (for NodePort services) - load balancers (ideally, connected to the pod network) - It is possible to use multiple pod networks in parallel (with "meta-plugins" like CNI-Genie or Multus) - Some solutions can fill multiple roles (e.g. kube-router can be set up to provide the pod network and/or network policies and/or replace kube-proxy) ??? :EN:- The Kubernetes network model :FR:- Le modèle réseau de Kubernetes .debug[[k8s/kubenet.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubenet.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-exposing-containers class: title Exposing containers .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-kubernetes-network-model) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-1) | [Next part](#toc-shipping-images-with-a-registry) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Exposing containers - We can connect to our pods using their IP address - Then we need to figure out a lot of things: - how do we look up the IP address of the pod(s)? - how do we connect from outside the cluster? - how do we load balance traffic? - what if a pod fails? - Kubernetes has a resource type named *Service* - Services address all these questions! .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- ## Services in a nutshell - Services give us a *stable endpoint* to connect to a pod or a group of pods - An easy way to create a service is to use `kubectl expose` - If we have a deployment named `my-little-deploy`, we can run: `kubectl expose deployment my-little-deploy --port=80` ... and this will create a service with the same name (`my-little-deploy`) - Services are automatically added to an internal DNS zone (in the example above, our code can now connect to http://my-little-deploy/) .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- ## Advantages of services - We don't need to look up the IP address of the pod(s) (we resolve the IP address of the service using DNS) - There are multiple service types; some of them allow external traffic (e.g. `LoadBalancer` and `NodePort`) - Services provide load balancing (for both internal and external traffic) - Service addresses are independent from pods' addresses (when a pod fails, the service seamlessly sends traffic to its replacement) .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- ## Many kinds and flavors of service - There are different types of services: `ClusterIP`, `NodePort`, `LoadBalancer`, `ExternalName` - There are also *headless services* - Services can also have optional *external IPs* - There is also another resource type called *Ingress* (specifically for HTTP services) - Wow, that's a lot! Let's start with the basics ... .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- ## `ClusterIP` - It's the default service type - A virtual IP address is allocated for the service (in an internal, private range; e.g. 10.96.0.0/12) - This IP address is reachable only from within the cluster (nodes and pods) - Our code can connect to the service using the original port number - Perfect for internal communication, within the cluster .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- ## `LoadBalancer` - An external load balancer is allocated for the service (typically a cloud load balancer, e.g. ELB on AWS, GLB on GCE ...) - This is available only when the underlying infrastructure provides some kind of "load balancer as a service" - Each service of that type will typically cost a little bit of money (e.g. a few cents per hour on AWS or GCE) - Ideally, traffic would flow directly from the load balancer to the pods - In practice, it will often flow through a `NodePort` first .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- ## `NodePort` - A port number is allocated for the service (by default, in the 30000-32767 range) - That port is made available *on all our nodes* and anybody can connect to it (we can connect to any node on that port to reach the service) - Our code needs to be changed to connect to that new port number - Under the hood: `kube-proxy` sets up a bunch of `iptables` rules on our nodes - Sometimes, it's the only available option for external traffic (e.g. most clusters deployed with kubeadm or on-premises) .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- ## Running containers with open ports - Since `ping` doesn't have anything to connect to, we'll have to run something else - We could use the `nginx` official image, but ... ... we wouldn't be able to tell the backends from each other! - We are going to use `jpetazzo/color`, a tiny HTTP server written in Go - `jpetazzo/color` listens on port 80 - It serves a page showing the pod's name (this will be useful when checking load balancing behavior) .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- ## Creating a deployment for our HTTP server - We will create a deployment with `kubectl create deployment` - Then we will scale it with `kubectl scale` .lab[ - In another window, watch the pods (to see when they are created): ```bash kubectl get pods -w ``` <!-- ```wait NAME``` ```tmux split-pane -h``` --> - Create a deployment for this very lightweight HTTP server: ```bash kubectl create deployment blue --image=jpetazzo/color ``` - Scale it to 10 replicas: ```bash kubectl scale deployment blue --replicas=10 ``` ] .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- ## Exposing our deployment - We'll create a default `ClusterIP` service .lab[ - Expose the HTTP port of our server: ```bash kubectl expose deployment blue --port=80 ``` - Look up which IP address was allocated: ```bash kubectl get service ``` ] .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- ## Services are layer 4 constructs - You can assign IP addresses to services, but they are still *layer 4* (i.e. a service is not an IP address; it's an IP address + protocol + port) - This is caused by the current implementation of `kube-proxy` (it relies on mechanisms that don't support layer 3) - As a result: you *have to* indicate the port number for your service (with some exceptions, like `ExternalName` or headless services, covered later) .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- ## Testing our service - We will now send a few HTTP requests to our pods .lab[ - Let's obtain the IP address that was allocated for our service, *programmatically:* ```bash IP=$(kubectl get svc blue -o go-template --template '{{ .spec.clusterIP }}') ``` <!-- ```hide kubectl wait deploy blue --for condition=available``` ```key ^D``` ```key ^C``` --> - Send a few requests: ```bash curl http://$IP:80/ ``` ] -- Try it a few times! Our requests are load balanced across multiple pods. .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- class: extra-details ## `ExternalName` - Services of type `ExternalName` are quite different - No load balancer (internal or external) is created - Only a DNS entry gets added to the DNS managed by Kubernetes - That DNS entry will just be a `CNAME` to a provided record Example: ```bash kubectl create service externalname k8s --external-name kubernetes.io ``` *Creates a CNAME `k8s` pointing to `kubernetes.io`* .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- class: extra-details ## External IPs - We can add an External IP to a service, e.g.: ```bash kubectl expose deploy my-little-deploy --port=80 --external-ip=1.2.3.4 ``` - `1.2.3.4` should be the address of one of our nodes (it could also be a virtual address, service address, or VIP, shared by multiple nodes) - Connections to `1.2.3.4:80` will be sent to our service - External IPs will also show up on services of type `LoadBalancer` (they will be added automatically by the process provisioning the load balancer) .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Headless services - Sometimes, we want to access our scaled services directly: - if we want to save a tiny little bit of latency (typically less than 1ms) - if we need to connect over arbitrary ports (instead of a few fixed ones) - if we need to communicate over another protocol than UDP or TCP - if we want to decide how to balance the requests client-side - ... - In that case, we can use a "headless service" .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Creating a headless services - A headless service is obtained by setting the `clusterIP` field to `None` (Either with `--cluster-ip=None`, or by providing a custom YAML) - As a result, the service doesn't have a virtual IP address - Since there is no virtual IP address, there is no load balancer either - CoreDNS will return the pods' IP addresses as multiple `A` records - This gives us an easy way to discover all the replicas for a deployment .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Services and endpoints - A service has a number of "endpoints" - Each endpoint is a host + port where the service is available - The endpoints are maintained and updated automatically by Kubernetes .lab[ - Check the endpoints that Kubernetes has associated with our `blue` service: ```bash kubectl describe service blue ``` ] In the output, there will be a line starting with `Endpoints:`. That line will list a bunch of addresses in `host:port` format. .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Viewing endpoint details - When we have many endpoints, our display commands truncate the list ```bash kubectl get endpoints ``` - If we want to see the full list, we can use one of the following commands: ```bash kubectl describe endpoints blue kubectl get endpoints blue -o yaml ``` - These commands will show us a list of IP addresses - These IP addresses should match the addresses of the corresponding pods: ```bash kubectl get pods -l app=blue -o wide ``` .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- class: extra-details ## `endpoints` not `endpoint` - `endpoints` is the only resource that cannot be singular ```bash $ kubectl get endpoint error: the server doesn't have a resource type "endpoint" ``` - This is because the type itself is plural (unlike every other resource) - There is no `endpoint` object: `type Endpoints struct` - The type doesn't represent a single endpoint, but a list of endpoints .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- class: extra-details ## The DNS zone - In the `kube-system` namespace, there should be a service named `kube-dns` - This is the internal DNS server that can resolve service names - The default domain name for the service we created is `default.svc.cluster.local` .lab[ - Get the IP address of the internal DNS server: ```bash IP=$(kubectl -n kube-system get svc kube-dns -o jsonpath={.spec.clusterIP}) ``` - Resolve the cluster IP for the `blue` service: ```bash host blue.default.svc.cluster.local $IP ``` ] .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- class: extra-details ## `Ingress` - Ingresses are another type (kind) of resource - They are specifically for HTTP services (not TCP or UDP) - They can also handle TLS certificates, URL rewriting ... - They require an *Ingress Controller* to function .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- class: pic  ??? :EN:- Service discovery and load balancing :EN:- Accessing pods through services :EN:- Service types: ClusterIP, NodePort, LoadBalancer :FR:- Exposer un service :FR:- Différents types de services : ClusterIP, NodePort, LoadBalancer :FR:- Utiliser CoreDNS pour la *service discovery* .debug[[k8s/kubectlexpose.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlexpose.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-shipping-images-with-a-registry class: title Shipping images with a registry .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-exposing-containers) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-1) | [Next part](#toc-exercise--deploy-dockercoins) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Shipping images with a registry - Initially, our app was running on a single node - We could *build* and *run* in the same place - Therefore, we did not need to *ship* anything - Now that we want to run on a cluster, things are different - The easiest way to ship container images is to use a registry .debug[[k8s/shippingimages.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/shippingimages.md)] --- ## How Docker registries work (a reminder) - What happens when we execute `docker run alpine` ? - If the Engine needs to pull the `alpine` image, it expands it into `library/alpine` - `library/alpine` is expanded into `index.docker.io/library/alpine` - The Engine communicates with `index.docker.io` to retrieve `library/alpine:latest` - To use something else than `index.docker.io`, we specify it in the image name - Examples: ```bash docker pull gcr.io/google-containers/alpine-with-bash:1.0 docker build -t registry.mycompany.io:5000/myimage:awesome . docker push registry.mycompany.io:5000/myimage:awesome ``` .debug[[k8s/shippingimages.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/shippingimages.md)] --- ## Running DockerCoins on Kubernetes - Create one deployment for each component (hasher, redis, rng, webui, worker) - Expose deployments that need to accept connections (hasher, redis, rng, webui) - For redis, we can use the official redis image - For the 4 others, we need to build images and push them to some registry .debug[[k8s/shippingimages.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/shippingimages.md)] --- ## Building and shipping images - There are *many* options! - Manually: - build locally (with `docker build` or otherwise) - push to the registry - Automatically: - build and test locally - when ready, commit and push a code repository - the code repository notifies an automated build system - that system gets the code, builds it, pushes the image to the registry .debug[[k8s/shippingimages.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/shippingimages.md)] --- ## Which registry do we want to use? - There are SAAS products like Docker Hub, Quay ... - Each major cloud provider has an option as well (ACR on Azure, ECR on AWS, GCR on Google Cloud...) - There are also commercial products to run our own registry (Docker EE, Quay...) - And open source options, too! - When picking a registry, pay attention to its build system (when it has one) .debug[[k8s/shippingimages.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/shippingimages.md)] --- ## Building on the fly - Conceptually, it is possible to build images on the fly from a repository - Example: [ctr.run](https://ctr.run/) (deprecated in August 2020, after being aquired by Datadog) - It did allow something like this: ```bash docker run ctr.run/github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/dockercoins/hasher ``` - No alternative yet (free startup idea, anyone?) ??? :EN:- Shipping images to Kubernetes :FR:- Déployer des images sur notre cluster .debug[[k8s/shippingimages.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/shippingimages.md)] --- ## Using images from the Docker Hub - For everyone's convenience, we took care of building DockerCoins images - We pushed these images to the DockerHub, under the [dockercoins](https://hub.docker.com/u/dockercoins) user - These images are *tagged* with a version number, `v0.1` - The full image names are therefore: - `dockercoins/hasher:v0.1` - `dockercoins/rng:v0.1` - `dockercoins/webui:v0.1` - `dockercoins/worker:v0.1` .debug[[k8s/buildshiprun-dockerhub.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/buildshiprun-dockerhub.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-exercise--deploy-dockercoins class: title Exercise — Deploy Dockercoins .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-shipping-images-with-a-registry) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-1) | [Next part](#toc-running-our-application-on-kubernetes) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Exercise — Deploy Dockercoins - We want to deploy the dockercoins app - There are 5 components in the app: hasher, redis, rng, webui, worker - We'll use one Deployment for each component (created with `kubectl create deployment`) - We'll connect them with Services (create with `kubectl expose`) .debug[[exercises/k8sfundamentals-details.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/exercises/k8sfundamentals-details.md)] --- ## Images - We'll use the following images: - hasher → `dockercoins/hasher:v0.1` - redis → `redis` - rng → `dockercoins/rng:v0.1` - webui → `dockercoins/webui:v0.1` - worker → `dockercoins/worker:v0.1` - All services should be internal services, except the web UI (since we want to be able to connect to the web UI from outside) .debug[[exercises/k8sfundamentals-details.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/exercises/k8sfundamentals-details.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[exercises/k8sfundamentals-details.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/exercises/k8sfundamentals-details.md)] --- ## Goal - We should be able to see the web UI in our browser (with the graph showing approximately 3-4 hashes/second) .debug[[exercises/k8sfundamentals-details.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/exercises/k8sfundamentals-details.md)] --- ## Hints - Make sure to expose services with the right ports (check the logs of the worker; they indicate the port numbers) - The web UI can be exposed with a NodePort or LoadBalancer Service .debug[[exercises/k8sfundamentals-details.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/exercises/k8sfundamentals-details.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-running-our-application-on-kubernetes class: title Running our application on Kubernetes .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-exercise--deploy-dockercoins) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-1) | [Next part](#toc-labels-and-annotations) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Running our application on Kubernetes - We can now deploy our code (as well as a redis instance) .lab[ - Deploy `redis`: ```bash kubectl create deployment redis --image=redis ``` - Deploy everything else: ```bash kubectl create deployment hasher --image=dockercoins/hasher:v0.1 kubectl create deployment rng --image=dockercoins/rng:v0.1 kubectl create deployment webui --image=dockercoins/webui:v0.1 kubectl create deployment worker --image=dockercoins/worker:v0.1 ``` ] .debug[[k8s/ourapponkube.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ourapponkube.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Deploying other images - If we wanted to deploy images from another registry ... - ... Or with a different tag ... - ... We could use the following snippet: ```bash REGISTRY=dockercoins TAG=v0.1 for SERVICE in hasher rng webui worker; do kubectl create deployment $SERVICE --image=$REGISTRY/$SERVICE:$TAG done ``` .debug[[k8s/ourapponkube.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ourapponkube.md)] --- ## Is this working? - After waiting for the deployment to complete, let's look at the logs! (Hint: use `kubectl get deploy -w` to watch deployment events) .lab[ <!-- ```hide kubectl wait deploy/rng --for condition=available kubectl wait deploy/worker --for condition=available ``` --> - Look at some logs: ```bash kubectl logs deploy/rng kubectl logs deploy/worker ``` ] -- 🤔 `rng` is fine ... But not `worker`. -- 💡 Oh right! We forgot to `expose`. .debug[[k8s/ourapponkube.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ourapponkube.md)] --- ## Connecting containers together - Three deployments need to be reachable by others: `hasher`, `redis`, `rng` - `worker` doesn't need to be exposed - `webui` will be dealt with later .lab[ - Expose each deployment, specifying the right port: ```bash kubectl expose deployment redis --port 6379 kubectl expose deployment rng --port 80 kubectl expose deployment hasher --port 80 ``` ] .debug[[k8s/ourapponkube.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ourapponkube.md)] --- ## Is this working yet? - The `worker` has an infinite loop, that retries 10 seconds after an error .lab[ - Stream the worker's logs: ```bash kubectl logs deploy/worker --follow ``` (Give it about 10 seconds to recover) <!-- ```wait units of work done, updating hash counter``` ```key ^C``` --> ] -- We should now see the `worker`, well, working happily. .debug[[k8s/ourapponkube.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ourapponkube.md)] --- ## Exposing services for external access - Now we would like to access the Web UI - We will expose it with a `NodePort` (just like we did for the registry) .lab[ - Create a `NodePort` service for the Web UI: ```bash kubectl expose deploy/webui --type=NodePort --port=80 ``` - Check the port that was allocated: ```bash kubectl get svc ``` ] .debug[[k8s/ourapponkube.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ourapponkube.md)] --- ## Accessing the web UI - We can now connect to *any node*, on the allocated node port, to view the web UI .lab[ - Open the web UI in your browser (http://node-ip-address:3xxxx/) <!-- ```open http://node1:3xxxx/``` --> ] -- Yes, this may take a little while to update. *(Narrator: it was DNS.)* -- *Alright, we're back to where we started, when we were running on a single node!* ??? :EN:- Running our demo app on Kubernetes :FR:- Faire tourner l'application de démo sur Kubernetes .debug[[k8s/ourapponkube.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ourapponkube.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-labels-and-annotations class: title Labels and annotations .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-running-our-application-on-kubernetes) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-2) | [Next part](#toc-revisiting-kubectl-logs) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Labels and annotations - Most Kubernetes resources can have *labels* and *annotations* - Both labels and annotations are arbitrary strings (with some limitations that we'll explain in a minute) - Both labels and annotations can be added, removed, changed, dynamically - This can be done with: - the `kubectl edit` command - the `kubectl label` and `kubectl annotate` - ... many other ways! (`kubectl apply -f`, `kubectl patch`, ...) .debug[[k8s/labels-annotations.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/labels-annotations.md)] --- ## Viewing labels and annotations - Let's see what we get when we create a Deployment .lab[ - Create a Deployment: ```bash kubectl create deployment clock --image=jpetazzo/clock ``` - Look at its annotations and labels: ```bash kubectl describe deployment clock ``` ] So, what do we get? .debug[[k8s/labels-annotations.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/labels-annotations.md)] --- ## Labels and annotations for our Deployment - We see one label: ``` Labels: app=clock ``` - This is added by `kubectl create deployment` - And one annotation: ``` Annotations: deployment.kubernetes.io/revision: 1 ``` - This is to keep track of successive versions when doing rolling updates .debug[[k8s/labels-annotations.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/labels-annotations.md)] --- ## And for the related Pod? - Let's look up the Pod that was created and check it too .lab[ - Find the name of the Pod: ```bash kubectl get pods ``` - Display its information: ```bash kubectl describe pod clock-xxxxxxxxxx-yyyyy ``` ] So, what do we get? .debug[[k8s/labels-annotations.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/labels-annotations.md)] --- ## Labels and annotations for our Pod - We see two labels: ``` Labels: app=clock pod-template-hash=xxxxxxxxxx ``` - `app=clock` comes from `kubectl create deployment` too - `pod-template-hash` was assigned by the Replica Set (when we will do rolling updates, each set of Pods will have a different hash) - There are no annotations: ``` Annotations: <none> ``` .debug[[k8s/labels-annotations.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/labels-annotations.md)] --- ## Selectors - A *selector* is an expression matching labels - It will restrict a command to the objects matching *at least* all these labels .lab[ - List all the pods with at least `app=clock`: ```bash kubectl get pods --selector=app=clock ``` - List all the pods with a label `app`, regardless of its value: ```bash kubectl get pods --selector=app ``` ] .debug[[k8s/labels-annotations.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/labels-annotations.md)] --- ## Settings labels and annotations - The easiest method is to use `kubectl label` and `kubectl annotate` .lab[ - Set a label on the `clock` Deployment: ```bash kubectl label deployment clock color=blue ``` - Check it out: ```bash kubectl describe deployment clock ``` ] .debug[[k8s/labels-annotations.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/labels-annotations.md)] --- ## Other ways to view labels - `kubectl get` gives us a couple of useful flags to check labels - `kubectl get --show-labels` shows all labels - `kubectl get -L xyz` shows the value of label `xyz` .lab[ - List all the labels that we have on pods: ```bash kubectl get pods --show-labels ``` - List the value of label `app` on these pods: ```bash kubectl get pods -L app ``` ] .debug[[k8s/labels-annotations.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/labels-annotations.md)] --- class: extra-details ## More on selectors - If a selector has multiple labels, it means "match at least these labels" Example: `--selector=app=frontend,release=prod` - `--selector` can be abbreviated as `-l` (for **l**abels) We can also use negative selectors Example: `--selector=app!=clock` - Selectors can be used with most `kubectl` commands Examples: `kubectl delete`, `kubectl label`, ... .debug[[k8s/labels-annotations.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/labels-annotations.md)] --- ## Other ways to view labels - We can use the `--show-labels` flag with `kubectl get` .lab[ - Show labels for a bunch of objects: ```bash kubectl get --show-labels po,rs,deploy,svc,no ``` ] .debug[[k8s/labels-annotations.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/labels-annotations.md)] --- ## Differences between labels and annotations - The *key* for both labels and annotations: - must start and end with a letter or digit - can also have `.` `-` `_` (but not in first or last position) - can be up to 63 characters, or 253 + `/` + 63 - Label *values* are up to 63 characters, with the same restrictions - Annotations *values* can have arbitrary characters (yes, even binary) - Maximum length isn't defined (dozens of kilobytes is fine, hundreds maybe not so much) ??? :EN:- Labels and annotations :FR:- *Labels* et annotations .debug[[k8s/labels-annotations.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/labels-annotations.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-revisiting-kubectl-logs class: title Revisiting `kubectl logs` .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-labels-and-annotations) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-2) | [Next part](#toc-accessing-logs-from-the-cli) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Revisiting `kubectl logs` - In this section, we assume that we have a Deployment with multiple Pods (e.g. `pingpong` that we scaled to at least 3 pods) - We will highlights some of the limitations of `kubectl logs` .debug[[k8s/kubectl-logs.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectl-logs.md)] --- ## Streaming logs of multiple pods - By default, `kubectl logs` shows us the output of a single Pod .lab[ - Try to check the output of the Pods related to a Deployment: ```bash kubectl logs deploy/pingpong --tail 1 --follow ``` <!-- ```wait using pod/pingpong-``` ```keys ^C``` --> ] `kubectl logs` only shows us the logs of one of the Pods. .debug[[k8s/kubectl-logs.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectl-logs.md)] --- ## Viewing logs of multiple pods - When we specify a deployment name, only one single pod's logs are shown - We can view the logs of multiple pods by specifying a *selector* - If we check the pods created by the deployment, they all have the label `app=pingpong` (this is just a default label that gets added when using `kubectl create deployment`) .lab[ - View the last line of log from all pods with the `app=pingpong` label: ```bash kubectl logs -l app=pingpong --tail 1 ``` ] .debug[[k8s/kubectl-logs.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectl-logs.md)] --- ## Streaming logs of multiple pods - Can we stream the logs of all our `pingpong` pods? .lab[ - Combine `-l` and `-f` flags: ```bash kubectl logs -l app=pingpong --tail 1 -f ``` <!-- ```wait seq=``` ```key ^C``` --> ] *Note: combining `-l` and `-f` is only possible since Kubernetes 1.14!* *Let's try to understand why ...* .debug[[k8s/kubectl-logs.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectl-logs.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Streaming logs of many pods - Let's see what happens if we try to stream the logs for more than 5 pods .lab[ - Scale up our deployment: ```bash kubectl scale deployment pingpong --replicas=8 ``` - Stream the logs: ```bash kubectl logs -l app=pingpong --tail 1 -f ``` <!-- ```wait error:``` --> ] We see a message like the following one: ``` error: you are attempting to follow 8 log streams, but maximum allowed concurency is 5, use --max-log-requests to increase the limit ``` .debug[[k8s/kubectl-logs.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectl-logs.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Why can't we stream the logs of many pods? - `kubectl` opens one connection to the API server per pod - For each pod, the API server opens one extra connection to the corresponding kubelet - If there are 1000 pods in our deployment, that's 1000 inbound + 1000 outbound connections on the API server - This could easily put a lot of stress on the API server - Prior Kubernetes 1.14, it was decided to *not* allow multiple connections - From Kubernetes 1.14, it is allowed, but limited to 5 connections (this can be changed with `--max-log-requests`) - For more details about the rationale, see [PR #67573](https://github.com/kubernetes/kubernetes/pull/67573) .debug[[k8s/kubectl-logs.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectl-logs.md)] --- ## Shortcomings of `kubectl logs` - We don't see which pod sent which log line - If pods are restarted / replaced, the log stream stops - If new pods are added, we don't see their logs - To stream the logs of multiple pods, we need to write a selector - There are external tools to address these shortcomings (e.g.: [Stern](https://github.com/stern/stern)) .debug[[k8s/kubectl-logs.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectl-logs.md)] --- class: extra-details ## `kubectl logs -l ... --tail N` - If we run this with Kubernetes 1.12, the last command shows multiple lines - This is a regression when `--tail` is used together with `-l`/`--selector` - It always shows the last 10 lines of output for each container (instead of the number of lines specified on the command line) - The problem was fixed in Kubernetes 1.13 *See [#70554](https://github.com/kubernetes/kubernetes/issues/70554) for details.* ??? :EN:- Viewing logs with "kubectl logs" :FR:- Consulter les logs avec "kubectl logs" .debug[[k8s/kubectl-logs.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectl-logs.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-accessing-logs-from-the-cli class: title Accessing logs from the CLI .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-revisiting-kubectl-logs) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-2) | [Next part](#toc-namespaces) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Accessing logs from the CLI - The `kubectl logs` command has limitations: - it cannot stream logs from multiple pods at a time - when showing logs from multiple pods, it mixes them all together - We are going to see how to do it better .debug[[k8s/logs-cli.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/logs-cli.md)] --- ## Doing it manually - We *could* (if we were so inclined) write a program or script that would: - take a selector as an argument - enumerate all pods matching that selector (with `kubectl get -l ...`) - fork one `kubectl logs --follow ...` command per container - annotate the logs (the output of each `kubectl logs ...` process) with their origin - preserve ordering by using `kubectl logs --timestamps ...` and merge the output -- - We *could* do it, but thankfully, others did it for us already! .debug[[k8s/logs-cli.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/logs-cli.md)] --- ## Stern [Stern](https://github.com/stern/stern) is an open source project originally by [Wercker](http://www.wercker.com/). From the README: *Stern allows you to tail multiple pods on Kubernetes and multiple containers within the pod. Each result is color coded for quicker debugging.* *The query is a regular expression so the pod name can easily be filtered and you don't need to specify the exact id (for instance omitting the deployment id). If a pod is deleted it gets removed from tail and if a new pod is added it automatically gets tailed.* Exactly what we need! .debug[[k8s/logs-cli.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/logs-cli.md)] --- ## Checking if Stern is installed - Run `stern` (without arguments) to check if it's installed: ``` $ stern Tail multiple pods and containers from Kubernetes Usage: stern pod-query [flags] ``` - If it's missing, let's see how to install it .debug[[k8s/logs-cli.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/logs-cli.md)] --- ## Installing Stern - Stern is written in Go - Go programs are usually very easy to install (no dependencies, extra libraries to install, etc) - Binary releases are available [on GitHub][stern-releases] - Stern is also available through most package managers (e.g. on macOS, we can `brew install stern` or `sudo port install stern`) [stern-releases]: https://github.com/stern/stern/releases .debug[[k8s/logs-cli.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/logs-cli.md)] --- ## Using Stern - There are two ways to specify the pods whose logs we want to see: - `-l` followed by a selector expression (like with many `kubectl` commands) - with a "pod query," i.e. a regex used to match pod names - These two ways can be combined if necessary .lab[ - View the logs for all the pingpong containers: ```bash stern pingpong ``` <!-- ```wait seq=``` ```key ^C``` --> ] .debug[[k8s/logs-cli.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/logs-cli.md)] --- ## Stern convenient options - The `--tail N` flag shows the last `N` lines for each container (Instead of showing the logs since the creation of the container) - The `-t` / `--timestamps` flag shows timestamps - The `--all-namespaces` flag is self-explanatory .lab[ - View what's up with the `weave` system containers: ```bash stern --tail 1 --timestamps --all-namespaces weave ``` <!-- ```wait weave-npc``` ```key ^C``` --> ] .debug[[k8s/logs-cli.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/logs-cli.md)] --- ## Using Stern with a selector - When specifying a selector, we can omit the value for a label - This will match all objects having that label (regardless of the value) - Everything created with `kubectl run` has a label `run` - Everything created with `kubectl create deployment` has a label `app` - We can use that property to view the logs of all the pods created with `kubectl create deployment` .lab[ - View the logs for all the things started with `kubectl create deployment`: ```bash stern -l app ``` <!-- ```wait seq=``` ```key ^C``` --> ] ??? :EN:- Viewing pod logs from the CLI :FR:- Consulter les logs des pods depuis la CLI .debug[[k8s/logs-cli.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/logs-cli.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-namespaces class: title Namespaces .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-accessing-logs-from-the-cli) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-2) | [Next part](#toc-deploying-with-yaml) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Namespaces - We would like to deploy another copy of DockerCoins on our cluster - We could rename all our deployments and services: hasher → hasher2, redis → redis2, rng → rng2, etc. - That would require updating the code - There has to be a better way! -- - As hinted by the title of this section, we will use *namespaces* .debug[[k8s/namespaces.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/namespaces.md)] --- ## Identifying a resource - We cannot have two resources with the same name (or can we...?) -- - We cannot have two resources *of the same kind* with the same name (but it's OK to have an `rng` service, an `rng` deployment, and an `rng` daemon set) -- - We cannot have two resources of the same kind with the same name *in the same namespace* (but it's OK to have e.g. two `rng` services in different namespaces) -- - Except for resources that exist at the *cluster scope* (these do not belong to a namespace) .debug[[k8s/namespaces.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/namespaces.md)] --- ## Uniquely identifying a resource - For *namespaced* resources: the tuple *(kind, name, namespace)* needs to be unique - For resources at the *cluster scope*: the tuple *(kind, name)* needs to be unique .lab[ - List resource types again, and check the NAMESPACED column: ```bash kubectl api-resources ``` ] .debug[[k8s/namespaces.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/namespaces.md)] --- ## Pre-existing namespaces - If we deploy a cluster with `kubeadm`, we have three or four namespaces: - `default` (for our applications) - `kube-system` (for the control plane) - `kube-public` (contains one ConfigMap for cluster discovery) - `kube-node-lease` (in Kubernetes 1.14 and later; contains Lease objects) - If we deploy differently, we may have different namespaces .debug[[k8s/namespaces.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/namespaces.md)] --- ## Creating namespaces - Let's see two identical methods to create a namespace .lab[ - We can use `kubectl create namespace`: ```bash kubectl create namespace blue ``` - Or we can construct a very minimal YAML snippet: ```bash kubectl apply -f- <<EOF apiVersion: v1 kind: Namespace metadata: name: blue EOF ``` ] .debug[[k8s/namespaces.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/namespaces.md)] --- ## Using namespaces - We can pass a `-n` or `--namespace` flag to most `kubectl` commands: ```bash kubectl -n blue get svc ``` - We can also change our current *context* - A context is a *(user, cluster, namespace)* tuple - We can manipulate contexts with the `kubectl config` command .debug[[k8s/namespaces.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/namespaces.md)] --- ## Viewing existing contexts - On our training environments, at this point, there should be only one context .lab[ - View existing contexts to see the cluster name and the current user: ```bash kubectl config get-contexts ``` ] - The current context (the only one!) is tagged with a `*` - What are NAME, CLUSTER, AUTHINFO, and NAMESPACE? .debug[[k8s/namespaces.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/namespaces.md)] --- ## What's in a context - NAME is an arbitrary string to identify the context - CLUSTER is a reference to a cluster (i.e. API endpoint URL, and optional certificate) - AUTHINFO is a reference to the authentication information to use (i.e. a TLS client certificate, token, or otherwise) - NAMESPACE is the namespace (empty string = `default`) .debug[[k8s/namespaces.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/namespaces.md)] --- ## Switching contexts - We want to use a different namespace - Solution 1: update the current context *This is appropriate if we need to change just one thing (e.g. namespace or authentication).* - Solution 2: create a new context and switch to it *This is appropriate if we need to change multiple things and switch back and forth.* - Let's go with solution 1! .debug[[k8s/namespaces.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/namespaces.md)] --- ## Updating a context - This is done through `kubectl config set-context` - We can update a context by passing its name, or the current context with `--current` .lab[ - Update the current context to use the `blue` namespace: ```bash kubectl config set-context --current --namespace=blue ``` - Check the result: ```bash kubectl config get-contexts ``` ] .debug[[k8s/namespaces.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/namespaces.md)] --- ## Using our new namespace - Let's check that we are in our new namespace, then deploy a new copy of Dockercoins .lab[ - Verify that the new context is empty: ```bash kubectl get all ``` ] .debug[[k8s/namespaces.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/namespaces.md)] --- ## Deploying DockerCoins with YAML files - The GitHub repository `jpetazzo/kubercoins` contains everything we need! .lab[ - Clone the kubercoins repository: ```bash cd ~ git clone https://github.com/jpetazzo/kubercoins ``` - Create all the DockerCoins resources: ```bash kubectl create -f kubercoins ``` ] If the argument behind `-f` is a directory, all the files in that directory are processed. The subdirectories are *not* processed, unless we also add the `-R` flag. .debug[[k8s/namespaces.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/namespaces.md)] --- ## Viewing the deployed app - Let's see if this worked correctly! .lab[ - Retrieve the port number allocated to the `webui` service: ```bash kubectl get svc webui ``` - Point our browser to http://X.X.X.X:3xxxx ] If the graph shows up but stays at zero, give it a minute or two! .debug[[k8s/namespaces.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/namespaces.md)] --- ## Namespaces and isolation - Namespaces *do not* provide isolation - A pod in the `green` namespace can communicate with a pod in the `blue` namespace - A pod in the `default` namespace can communicate with a pod in the `kube-system` namespace - CoreDNS uses a different subdomain for each namespace - Example: from any pod in the cluster, you can connect to the Kubernetes API with: `https://kubernetes.default.svc.cluster.local:443/` .debug[[k8s/namespaces.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/namespaces.md)] --- ## Isolating pods - Actual isolation is implemented with *network policies* - Network policies are resources (like deployments, services, namespaces...) - Network policies specify which flows are allowed: - between pods - from pods to the outside world - and vice-versa .debug[[k8s/namespaces.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/namespaces.md)] --- ## Switch back to the default namespace - Let's make sure that we don't run future exercises and labs in the `blue` namespace .lab[ - Switch back to the original context: ```bash kubectl config set-context --current --namespace= ``` ] Note: we could have used `--namespace=default` for the same result. .debug[[k8s/namespaces.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/namespaces.md)] --- ## Switching namespaces more easily - We can also use a little helper tool called `kubens`: ```bash # Switch to namespace foo kubens foo # Switch back to the previous namespace kubens - ``` - On our clusters, `kubens` is called `kns` instead (so that it's even fewer keystrokes to switch namespaces) .debug[[k8s/namespaces.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/namespaces.md)] --- ## `kubens` and `kubectx` - With `kubens`, we can switch quickly between namespaces - With `kubectx`, we can switch quickly between contexts - Both tools are simple shell scripts available from https://github.com/ahmetb/kubectx - On our clusters, they are installed as `kns` and `kctx` (for brevity and to avoid completion clashes between `kubectx` and `kubectl`) .debug[[k8s/namespaces.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/namespaces.md)] --- ## `kube-ps1` - It's easy to lose track of our current cluster / context / namespace - `kube-ps1` makes it easy to track these, by showing them in our shell prompt - It is installed on our training clusters, and when using [shpod](https://github.com/jpetazzo/shpod) - It gives us a prompt looking like this one: ``` [123.45.67.89] `(kubernetes-admin@kubernetes:default)` docker@node1 ~ ``` (The highlighted part is `context:namespace`, managed by `kube-ps1`) - Highly recommended if you work across multiple contexts or namespaces! .debug[[k8s/namespaces.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/namespaces.md)] --- ## Installing `kube-ps1` - It's a simple shell script available from https://github.com/jonmosco/kube-ps1 - It needs to be [installed in our profile/rc files](https://github.com/jonmosco/kube-ps1#installing) (instructions differ depending on platform, shell, etc.) - Once installed, it defines aliases called `kube_ps1`, `kubeon`, `kubeoff` (to selectively enable/disable it when needed) - Pro-tip: install it on your machine during the next break! ??? :EN:- Organizing resources with Namespaces :FR:- Organiser les ressources avec des *namespaces* .debug[[k8s/namespaces.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/namespaces.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-deploying-with-yaml class: title Deploying with YAML .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-namespaces) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-2) | [Next part](#toc-declarative-vs-imperative) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Deploying with YAML - So far, we created resources with the following commands: - `kubectl run` - `kubectl create deployment` - `kubectl expose` - We can also create resources directly with YAML manifests .debug[[k8s/yamldeploy.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/yamldeploy.md)] --- ## `kubectl apply` vs `create` - `kubectl create -f whatever.yaml` - creates resources if they don't exist - if resources already exist, don't alter them <br/>(and display error message) - `kubectl apply -f whatever.yaml` - creates resources if they don't exist - if resources already exist, update them <br/>(to match the definition provided by the YAML file) - stores the manifest as an *annotation* in the resource .debug[[k8s/yamldeploy.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/yamldeploy.md)] --- ## Creating multiple resources - The manifest can contain multiple resources separated by `---` ```yaml kind: ... apiVersion: ... metadata: ... name: ... ... --- kind: ... apiVersion: ... metadata: ... name: ... ... ``` .debug[[k8s/yamldeploy.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/yamldeploy.md)] --- ## Creating multiple resources - The manifest can also contain a list of resources ```yaml apiVersion: v1 kind: List items: - kind: ... apiVersion: ... ... - kind: ... apiVersion: ... ... ``` .debug[[k8s/yamldeploy.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/yamldeploy.md)] --- ## Deploying dockercoins with YAML - We provide a YAML manifest with all the resources for Dockercoins (Deployments and Services) - We can use it if we need to deploy or redeploy Dockercoins .lab[ - Deploy or redeploy Dockercoins: ```bash kubectl apply -f ~/container.training/k8s/dockercoins.yaml ``` ] (If we deployed Dockercoins earlier, we will see warning messages, because the resources that we created lack the necessary annotation. We can safely ignore them.) .debug[[k8s/yamldeploy.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/yamldeploy.md)] --- ## Deleting resources - We can also use a YAML file to *delete* resources - `kubectl delete -f ...` will delete all the resources mentioned in a YAML file (useful to clean up everything that was created by `kubectl apply -f ...`) - The definitions of the resources don't matter (just their `kind`, `apiVersion`, and `name`) .debug[[k8s/yamldeploy.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/yamldeploy.md)] --- ## Pruning¹ resources - We can also tell `kubectl` to remove old resources - This is done with `kubectl apply -f ... --prune` - It will remove resources that don't exist in the YAML file(s) - But only if they were created with `kubectl apply` in the first place (technically, if they have an annotation `kubectl.kubernetes.io/last-applied-configuration`) .footnote[¹If English is not your first language: *to prune* means to remove dead or overgrown branches in a tree, to help it to grow.] .debug[[k8s/yamldeploy.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/yamldeploy.md)] --- ## YAML as source of truth - Imagine the following workflow: - do not use `kubectl run`, `kubectl create deployment`, `kubectl expose` ... - define everything with YAML - `kubectl apply -f ... --prune --all` that YAML - keep that YAML under version control - enforce all changes to go through that YAML (e.g. with pull requests) - Our version control system now has a full history of what we deploy - Compares to "Infrastructure-as-Code", but for app deployments .debug[[k8s/yamldeploy.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/yamldeploy.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Specifying the namespace - When creating resources from YAML manifests, the namespace is optional - If we specify a namespace: - resources are created in the specified namespace - this is typical for things deployed only once per cluster - example: system components, cluster add-ons ... - If we don't specify a namespace: - resources are created in the current namespace - this is typical for things that may be deployed multiple times - example: applications (production, staging, feature branches ...) ??? :EN:- Deploying with YAML manifests :FR:- Déployer avec des *manifests* YAML .debug[[k8s/yamldeploy.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/yamldeploy.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-declarative-vs-imperative class: title Declarative vs imperative .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-deploying-with-yaml) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-2) | [Next part](#toc-authoring-yaml) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Declarative vs imperative - Our container orchestrator puts a very strong emphasis on being *declarative* - Declarative: *I would like a cup of tea.* - Imperative: *Boil some water. Pour it in a teapot. Add tea leaves. Steep for a while. Serve in a cup.* -- - Declarative seems simpler at first ... -- - ... As long as you know how to brew tea .debug[[shared/declarative.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/declarative.md)] --- ## Declarative vs imperative - What declarative would really be: *I want a cup of tea, obtained by pouring an infusion¹ of tea leaves in a cup.* -- *¹An infusion is obtained by letting the object steep a few minutes in hot² water.* -- *²Hot liquid is obtained by pouring it in an appropriate container³ and setting it on a stove.* -- *³Ah, finally, containers! Something we know about. Let's get to work, shall we?* -- .footnote[Did you know there was an [ISO standard](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ISO_3103) specifying how to brew tea?] .debug[[shared/declarative.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/declarative.md)] --- ## Declarative vs imperative - Imperative systems: - simpler - if a task is interrupted, we have to restart from scratch - Declarative systems: - if a task is interrupted (or if we show up to the party half-way through), we can figure out what's missing and do only what's necessary - we need to be able to *observe* the system - ... and compute a "diff" between *what we have* and *what we want* .debug[[shared/declarative.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/declarative.md)] --- ## Declarative vs imperative in Kubernetes - With Kubernetes, we cannot say: "run this container" - All we can do is write a *spec* and push it to the API server (by creating a resource like e.g. a Pod or a Deployment) - The API server will validate that spec (and reject it if it's invalid) - Then it will store it in etcd - A *controller* will "notice" that spec and act upon it .debug[[k8s/declarative.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/declarative.md)] --- ## Reconciling state - Watch for the `spec` fields in the YAML files later! - The *spec* describes *how we want the thing to be* - Kubernetes will *reconcile* the current state with the spec <br/>(technically, this is done by a number of *controllers*) - When we want to change some resource, we update the *spec* - Kubernetes will then *converge* that resource ??? :EN:- Declarative vs imperative models :FR:- Modèles déclaratifs et impératifs .debug[[k8s/declarative.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/declarative.md)] --- ## 19,000 words They say, "a picture is worth one thousand words." The following 19 slides show what really happens when we run: ```bash kubectl create deployment web --image=nginx ``` .debug[[k8s/deploymentslideshow.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/deploymentslideshow.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/deploymentslideshow.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/deploymentslideshow.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/deploymentslideshow.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/deploymentslideshow.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/deploymentslideshow.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/deploymentslideshow.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/deploymentslideshow.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/deploymentslideshow.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/deploymentslideshow.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/deploymentslideshow.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/deploymentslideshow.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/deploymentslideshow.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/deploymentslideshow.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/deploymentslideshow.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/deploymentslideshow.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/deploymentslideshow.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/deploymentslideshow.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/deploymentslideshow.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/deploymentslideshow.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/deploymentslideshow.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/deploymentslideshow.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/deploymentslideshow.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/deploymentslideshow.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/deploymentslideshow.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/deploymentslideshow.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/deploymentslideshow.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/deploymentslideshow.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/deploymentslideshow.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/deploymentslideshow.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/deploymentslideshow.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/deploymentslideshow.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/deploymentslideshow.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/deploymentslideshow.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/deploymentslideshow.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/deploymentslideshow.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/deploymentslideshow.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/deploymentslideshow.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/deploymentslideshow.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-authoring-yaml class: title Authoring YAML .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-declarative-vs-imperative) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-2) | [Next part](#toc-setting-up-kubernetes) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Authoring YAML - We have already generated YAML implicitly, with e.g.: - `kubectl run` - `kubectl create deployment` (and a few other `kubectl create` variants) - `kubectl expose` - When and why do we need to write our own YAML? - How do we write YAML from scratch? .debug[[k8s/authoring-yaml.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authoring-yaml.md)] --- ## The limits of generated YAML - Many advanced (and even not-so-advanced) features require to write YAML: - pods with multiple containers - resource limits - healthchecks - DaemonSets, StatefulSets - and more! - How do we access these features? .debug[[k8s/authoring-yaml.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authoring-yaml.md)] --- ## Various ways to write YAML - Completely from scratch with our favorite editor (yeah, right) - Dump an existing resource with `kubectl get -o yaml ...` (it is recommended to clean up the result) - Ask `kubectl` to generate the YAML (with a `kubectl create --dry-run=client -o yaml`) - Use The Docs, Luke (the documentation almost always has YAML examples) .debug[[k8s/authoring-yaml.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authoring-yaml.md)] --- ## Generating YAML from scratch - Start with a namespace: ```yaml kind: Namespace apiVersion: v1 metadata: name: hello ``` - We can use `kubectl explain` to see resource definitions: ```bash kubectl explain -r pod.spec ``` - Not the easiest option! .debug[[k8s/authoring-yaml.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authoring-yaml.md)] --- ## Dump the YAML for an existing resource - `kubectl get -o yaml` works! - A lot of fields in `metadata` are not necessary (`managedFields`, `resourceVersion`, `uid`, `creationTimestamp` ...) - Most objects will have a `status` field that is not necessary - Default or empty values can also be removed for clarity - This can be done manually or with the `kubectl-neat` plugin `kubectl get -o yaml ... | kubectl neat` .debug[[k8s/authoring-yaml.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authoring-yaml.md)] --- ## Generating YAML without creating resources - We can use the `--dry-run=client` option .lab[ - Generate the YAML for a Deployment without creating it: ```bash kubectl create deployment web --image nginx --dry-run=client ``` - Optionally clean it up with `kubectl neat`, too ] .debug[[k8s/authoring-yaml.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authoring-yaml.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Using `--dry-run` with `kubectl apply` - The `--dry-run` option can also be used with `kubectl apply` - However, it can be misleading (it doesn't do a "real" dry run) - Let's see what happens in the following scenario: - generate the YAML for a Deployment - tweak the YAML to transform it into a DaemonSet - apply that YAML to see what would actually be created .debug[[k8s/authoring-yaml.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authoring-yaml.md)] --- class: extra-details ## The limits of `kubectl apply --dry-run=client` .lab[ - Generate the YAML for a deployment: ```bash kubectl create deployment web --image=nginx -o yaml > web.yaml ``` - Change the `kind` in the YAML to make it a `DaemonSet`: ```bash sed -i s/Deployment/DaemonSet/ web.yaml ``` - Ask `kubectl` what would be applied: ```bash kubectl apply -f web.yaml --dry-run=client --validate=false -o yaml ``` ] The resulting YAML doesn't represent a valid DaemonSet. .debug[[k8s/authoring-yaml.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authoring-yaml.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Server-side dry run - Since Kubernetes 1.13, we can use [server-side dry run and diffs](https://kubernetes.io/blog/2019/01/14/apiserver-dry-run-and-kubectl-diff/) - Server-side dry run will do all the work, but *not* persist to etcd (all validation and mutation hooks will be executed) .lab[ - Try the same YAML file as earlier, with server-side dry run: ```bash kubectl apply -f web.yaml --dry-run=server --validate=false -o yaml ``` ] The resulting YAML doesn't have the `replicas` field anymore. Instead, it has the fields expected in a DaemonSet. .debug[[k8s/authoring-yaml.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authoring-yaml.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Advantages of server-side dry run - The YAML is verified much more extensively - The only step that is skipped is "write to etcd" - YAML that passes server-side dry run *should* apply successfully (unless the cluster state changes by the time the YAML is actually applied) - Validating or mutating hooks that have side effects can also be an issue .debug[[k8s/authoring-yaml.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authoring-yaml.md)] --- class: extra-details ## `kubectl diff` - Kubernetes 1.13 also introduced `kubectl diff` - `kubectl diff` does a server-side dry run, *and* shows differences .lab[ - Try `kubectl diff` on the YAML that we tweaked earlier: ```bash kubectl diff -f web.yaml ``` <!-- ```wait status:``` --> ] Note: we don't need to specify `--validate=false` here. .debug[[k8s/authoring-yaml.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authoring-yaml.md)] --- ## Advantage of YAML - Using YAML (instead of `kubectl create <kind>`) allows to be *declarative* - The YAML describes the desired state of our cluster and applications - YAML can be stored, versioned, archived (e.g. in git repositories) - To change resources, change the YAML files (instead of using `kubectl edit`/`scale`/`label`/etc.) - Changes can be reviewed before being applied (with code reviews, pull requests ...) - This workflow is sometimes called "GitOps" (there are tools like Weave Flux or GitKube to facilitate it) .debug[[k8s/authoring-yaml.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authoring-yaml.md)] --- ## YAML in practice - Get started with `kubectl create deployment` and `kubectl expose` (until you have something that works) - Then, run these commands again, but with `-o yaml --dry-run=client` (to generate and save YAML manifests) - Try to apply these manifests in a clean environment (e.g. a new Namespace) - Check that everything works; tweak and iterate if needed - Commit the YAML to a repo 💯🏆️ .debug[[k8s/authoring-yaml.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authoring-yaml.md)] --- ## "Day 2" YAML - Don't hesitate to remove unused fields (e.g. `creationTimestamp: null`, most `{}` values...) - Check your YAML with: [kube-score](https://github.com/zegl/kube-score) (installable with krew) [kube-linter](https://github.com/stackrox/kube-linter) - Check live resources with tools like [popeye](https://popeyecli.io/) - Remember that like all linters, they need to be configured for your needs! ??? :EN:- Techniques to write YAML manifests :FR:- Comment écrire des *manifests* YAML .debug[[k8s/authoring-yaml.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authoring-yaml.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-setting-up-kubernetes class: title Setting up Kubernetes .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-authoring-yaml) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-2) | [Next part](#toc-running-a-local-development-cluster) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Setting up Kubernetes - Kubernetes is made of many components that require careful configuration - Secure operation typically requires TLS certificates and a local CA (certificate authority) - Setting up everything manually is possible, but rarely done (except for learning purposes) - Let's do a quick overview of available options! .debug[[k8s/setup-overview.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/setup-overview.md)] --- ## Local development - Are you writing code that will eventually run on Kubernetes? - Then it's a good idea to have a development cluster! - Instead of shipping containers images, we can test them on Kubernetes - Extremely useful when authoring or testing Kubernetes-specific objects (ConfigMaps, Secrets, StatefulSets, Jobs, RBAC, etc.) - Extremely convenient to quickly test/check what a particular thing looks like (e.g. what are the fields a Deployment spec?) .debug[[k8s/setup-overview.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/setup-overview.md)] --- ## One-node clusters - It's perfectly fine to work with a cluster that has only one node - It simplifies a lot of things: - pod networking doesn't even need CNI plugins, overlay networks, etc. - these clusters can be fully contained (no pun intended) in an easy-to-ship VM or container image - some of the security aspects may be simplified (different threat model) - images can be built directly on the node (we don't need to ship them with a registry) - Examples: Docker Desktop, k3d, KinD, MicroK8s, Minikube (some of these also support clusters with multiple nodes) .debug[[k8s/setup-overview.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/setup-overview.md)] --- ## Managed clusters ("Turnkey Solutions") - Many cloud providers and hosting providers offer "managed Kubernetes" - The deployment and maintenance of the *control plane* is entirely managed by the provider (ideally, clusters can be spun up automatically through an API, CLI, or web interface) - Given the complexity of Kubernetes, this approach is *strongly recommended* (at least for your first production clusters) - After working for a while with Kubernetes, you will be better equipped to decide: - whether to operate it yourself or use a managed offering - which offering or which distribution works best for you and your needs .debug[[k8s/setup-overview.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/setup-overview.md)] --- ## Node management - Most "Turnkey Solutions" offer fully managed control planes (including control plane upgrades, sometimes done automatically) - However, with most providers, we still need to take care of *nodes* (provisioning, upgrading, scaling the nodes) - Example with Amazon EKS ["managed node groups"](https://docs.aws.amazon.com/eks/latest/userguide/managed-node-groups.html): *...when bugs or issues are reported [...] you're responsible for deploying these patched AMI versions to your managed node groups.* .debug[[k8s/setup-overview.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/setup-overview.md)] --- ## Managed clusters differences - Most providers let you pick which Kubernetes version you want - some providers offer up-to-date versions - others lag significantly (sometimes by 2 or 3 minor versions) - Some providers offer multiple networking or storage options - Others will only support one, tied to their infrastructure (changing that is in theory possible, but might be complex or unsupported) - Some providers let you configure or customize the control plane (generally through Kubernetes "feature gates") .debug[[k8s/setup-overview.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/setup-overview.md)] --- ## Choosing a provider - Pricing models differ from one provider to another - nodes are generally charged at their usual price - control plane may be free or incur a small nominal fee - Beyond pricing, there are *huge* differences in features between providers - The "major" providers are not always the best ones! - See [this page](https://kubernetes.io/docs/setup/production-environment/turnkey-solutions/) for a list of available providers .debug[[k8s/setup-overview.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/setup-overview.md)] --- ## Kubernetes distributions and installers - If you want to run Kubernetes yourselves, there are many options (free, commercial, proprietary, open source ...) - Some of them are installers, while some are complete platforms - Some of them leverage other well-known deployment tools (like Puppet, Terraform ...) - There are too many options to list them all (check [this page](https://kubernetes.io/partners/#conformance) for an overview!) .debug[[k8s/setup-overview.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/setup-overview.md)] --- ## kubeadm - kubeadm is a tool part of Kubernetes to facilitate cluster setup - Many other installers and distributions use it (but not all of them) - It can also be used by itself - Excellent starting point to install Kubernetes on your own machines (virtual, physical, it doesn't matter) - It even supports highly available control planes, or "multi-master" (this is more complex, though, because it introduces the need for an API load balancer) .debug[[k8s/setup-overview.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/setup-overview.md)] --- ## Manual setup - The resources below are mainly for educational purposes! - [Kubernetes The Hard Way](https://github.com/kelseyhightower/kubernetes-the-hard-way) by Kelsey Hightower - step by step guide to install Kubernetes on Google Cloud - covers certificates, high availability ... - *“Kubernetes The Hard Way is optimized for learning, which means taking the long route to ensure you understand each task required to bootstrap a Kubernetes cluster.”* - [Deep Dive into Kubernetes Internals for Builders and Operators](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3KtEAa7_duA) - conference presentation showing step-by-step control plane setup - emphasis on simplicity, not on security and availability .debug[[k8s/setup-overview.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/setup-overview.md)] --- ## About our training clusters - How did we set up these Kubernetes clusters that we're using? -- - We used `kubeadm` on freshly installed VM instances running Ubuntu LTS 1. Install Docker 2. Install Kubernetes packages 3. Run `kubeadm init` on the first node (it deploys the control plane on that node) 4. Set up Weave (the overlay network) with a single `kubectl apply` command 5. Run `kubeadm join` on the other nodes (with the token produced by `kubeadm init`) 6. Copy the configuration file generated by `kubeadm init` - Check the [prepare VMs README](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/blob/master/prepare-vms/README.md) for more details .debug[[k8s/setup-overview.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/setup-overview.md)] --- ## `kubeadm` "drawbacks" - Doesn't set up Docker or any other container engine (this is by design, to give us choice) - Doesn't set up the overlay network (this is also by design, for the same reasons) - HA control plane requires [some extra steps](https://kubernetes.io/docs/setup/independent/high-availability/) - Note that HA control plane also requires setting up a specific API load balancer (which is beyond the scope of kubeadm) ??? :EN:- Various ways to install Kubernetes :FR:- Survol des techniques d'installation de Kubernetes .debug[[k8s/setup-overview.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/setup-overview.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-running-a-local-development-cluster class: title Running a local development cluster .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-setting-up-kubernetes) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-2) | [Next part](#toc-controlling-a-kubernetes-cluster-remotely) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Running a local development cluster - Let's review some options to run Kubernetes locally - There is no "best option", it depends what you value: - ability to run on all platforms (Linux, Mac, Windows, other?) - ability to run clusters with multiple nodes - ability to run multiple clusters side by side - ability to run recent (or even, unreleased) versions of Kubernetes - availability of plugins - etc. .debug[[k8s/setup-devel.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/setup-devel.md)] --- ### CoLiMa - Container runtimes for LiMa (LiMa = Linux on macOS) - For macOS only (Intel and ARM architectures) - CLI-driven (no GUI like Docker/Rancher Desktop) - Supports containerd, Docker, Kubernetes - Installable with brew, nix, or ports - More info: https://github.com/abiosoft/colima .debug[[k8s/setup-devel.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/setup-devel.md)] --- ## Docker Desktop - Available on Linux, Mac, and Windows - Free for personal use and small businesses (less than 250 employees and less than $10 millions in annual revenue) - Gives you one cluster with one node - Streamlined installation and user experience - Great integration with various network stacks and e.g. corporate VPNs - Ideal for Docker users who need good integration between both platforms .debug[[k8s/setup-devel.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/setup-devel.md)] --- ## [k3d](https://k3d.io/) - Based on [K3s](https://k3s.io/) by Rancher Labs - Requires Docker - Runs Kubernetes nodes in Docker containers - Can deploy multiple clusters, with multiple nodes - Runs the control plane on Kubernetes nodes - Control plane can also run on multiple nodes .debug[[k8s/setup-devel.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/setup-devel.md)] --- ## k3d in action - Install `k3d` (e.g. get the binary from https://github.com/rancher/k3d/releases) - Create a simple cluster: ```bash k3d cluster create petitcluster ``` - Create a more complex cluster with a custom version: ```bash k3d cluster create groscluster \ --image rancher/k3s:v1.18.9-k3s1 --servers 3 --agents 5 ``` (3 nodes for the control plane + 5 worker nodes) - Clusters are automatically added to `.kube/config` file .debug[[k8s/setup-devel.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/setup-devel.md)] --- ## [KinD](https://kind.sigs.k8s.io/) - Kubernetes-in-Docker - Requires Docker (obviously!) - Should also work with Podman and Rootless Docker - Deploying a single node cluster using the latest version is simple: ```bash kind create cluster ``` - More advanced scenarios require writing a short [config file](https://kind.sigs.k8s.io/docs/user/quick-start#configuring-your-kind-cluster) (to define multiple nodes, multiple control plane nodes, set Kubernetes versions ...) - Can deploy multiple clusters .debug[[k8s/setup-devel.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/setup-devel.md)] --- ## [MicroK8s](https://microk8s.io/) - Available on Linux, and since recently, on Mac and Windows as well - The Linux version is installed through Snap (which is pre-installed on all recent versions of Ubuntu) - Also supports clustering (as in, multiple machines running MicroK8s) - DNS is not enabled by default; enable it with `microk8s enable dns` .debug[[k8s/setup-devel.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/setup-devel.md)] --- ## [Minikube](https://minikube.sigs.k8s.io/docs/) - The "legacy" option! (note: this is not a bad thing, it means that it's very stable, has lots of plugins, etc.) - Supports many [drivers](https://minikube.sigs.k8s.io/docs/drivers/) (HyperKit, Hyper-V, KVM, VirtualBox, but also Docker and many others) - Can deploy a single cluster; recent versions can deploy multiple nodes - Great option if you want a "Kubernetes first" experience (i.e. if you don't already have Docker and/or don't want/need it) .debug[[k8s/setup-devel.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/setup-devel.md)] --- ## [Rancher Desktop](https://rancherdesktop.io/) - Available on Linux, Mac, and Windows - Free and open-source - Runs a single cluster with a single node - Lets you pick the Kubernetes version that you want to use (and change it any time you like) - Emphasis on ease of use (like Docker Desktop) - Relatively young product (first release in May 2021) - Based on k3s and other proven components .debug[[k8s/setup-devel.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/setup-devel.md)] --- ## VM with custom install - Choose your own adventure! - Pick any Linux distribution! - Build your cluster from scratch or use a Kubernetes installer! - Discover exotic CNI plugins and container runtimes! - The only limit is yourself, and the time you are willing to sink in! ??? :EN:- Kubernetes options for local development :FR:- Installation de Kubernetes pour travailler en local .debug[[k8s/setup-devel.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/setup-devel.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-controlling-a-kubernetes-cluster-remotely class: title Controlling a Kubernetes cluster remotely .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-running-a-local-development-cluster) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-2) | [Next part](#toc-accessing-internal-services) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Controlling a Kubernetes cluster remotely - `kubectl` can be used either on cluster instances or outside the cluster - Here, we are going to use `kubectl` from our local machine .debug[[k8s/localkubeconfig.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/localkubeconfig.md)] --- ## Requirements .warning[The commands in this chapter should be run *on your local machine*.] - `kubectl` is officially available on Linux, macOS, Windows (and unofficially anywhere we can build and run Go binaries) - You may skip these commands if you are following along from: - a tablet or phone - a web-based terminal - an environment where you can't install and run new binaries .debug[[k8s/localkubeconfig.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/localkubeconfig.md)] --- ## Installing `kubectl` - If you already have `kubectl` on your local machine, you can skip this .lab[ <!-- ##VERSION## --> - Download the `kubectl` binary from one of these links: [Linux](https://storage.googleapis.com/kubernetes-release/release/v1.19.2/bin/linux/amd64/kubectl) | [macOS](https://storage.googleapis.com/kubernetes-release/release/v1.19.2/bin/darwin/amd64/kubectl) | [Windows](https://storage.googleapis.com/kubernetes-release/release/v1.19.2/bin/windows/amd64/kubectl.exe) - On Linux and macOS, make the binary executable with `chmod +x kubectl` (And remember to run it with `./kubectl` or move it to your `$PATH`) ] Note: if you are following along with a different platform (e.g. Linux on an architecture different from amd64, or with a phone or tablet), installing `kubectl` might be more complicated (or even impossible) so feel free to skip this section. .debug[[k8s/localkubeconfig.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/localkubeconfig.md)] --- ## Testing `kubectl` - Check that `kubectl` works correctly (before even trying to connect to a remote cluster!) .lab[ - Ask `kubectl` to show its version number: ```bash kubectl version --client ``` ] The output should look like this: ``` Client Version: version.Info{Major:"1", Minor:"15", GitVersion:"v1.15.0", GitCommit:"e8462b5b5dc2584fdcd18e6bcfe9f1e4d970a529", GitTreeState:"clean", BuildDate:"2019-06-19T16:40:16Z", GoVersion:"go1.12.5", Compiler:"gc", Platform:"darwin/amd64"} ``` .debug[[k8s/localkubeconfig.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/localkubeconfig.md)] --- ## Preserving the existing `~/.kube/config` - If you already have a `~/.kube/config` file, rename it (we are going to overwrite it in the following slides!) - If you never used `kubectl` on your machine before: nothing to do! .lab[ - Make a copy of `~/.kube/config`; if you are using macOS or Linux, you can do: ```bash cp ~/.kube/config ~/.kube/config.before.training ``` - If you are using Windows, you will need to adapt this command ] .debug[[k8s/localkubeconfig.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/localkubeconfig.md)] --- ## Copying the configuration file from `node1` - The `~/.kube/config` file that is on `node1` contains all the credentials we need - Let's copy it over! .lab[ - Copy the file from `node1`; if you are using macOS or Linux, you can do: ``` scp `USER`@`X.X.X.X`:.kube/config ~/.kube/config # Make sure to replace X.X.X.X with the IP address of node1, # and USER with the user name used to log into node1! ``` - If you are using Windows, adapt these instructions to your SSH client ] .debug[[k8s/localkubeconfig.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/localkubeconfig.md)] --- ## Updating the server address - There is a good chance that we need to update the server address - To know if it is necessary, run `kubectl config view` - Look for the `server:` address: - if it matches the public IP address of `node1`, you're good! - if it is anything else (especially a private IP address), update it! - To update the server address, run: ```bash kubectl config set-cluster kubernetes --server=https://`X.X.X.X`:6443 # Make sure to replace X.X.X.X with the IP address of node1! ``` .debug[[k8s/localkubeconfig.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/localkubeconfig.md)] --- class: extra-details ## What if we get a certificate error? - Generally, the Kubernetes API uses a certificate that is valid for: - `kubernetes` - `kubernetes.default` - `kubernetes.default.svc` - `kubernetes.default.svc.cluster.local` - the ClusterIP address of the `kubernetes` service - the hostname of the node hosting the control plane (e.g. `node1`) - the IP address of the node hosting the control plane - On most clouds, the IP address of the node is an internal IP address - ... And we are going to connect over the external IP address - ... And that external IP address was not used when creating the certificate! .debug[[k8s/localkubeconfig.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/localkubeconfig.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Working around the certificate error - We need to tell `kubectl` to skip TLS verification (only do this with testing clusters, never in production!) - The following command will do the trick: ```bash kubectl config set-cluster kubernetes --insecure-skip-tls-verify ``` .debug[[k8s/localkubeconfig.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/localkubeconfig.md)] --- ## Checking that we can connect to the cluster - We can now run a couple of trivial commands to check that all is well .lab[ - Check the versions of the local client and remote server: ```bash kubectl version ``` - View the nodes of the cluster: ```bash kubectl get nodes ``` ] We can now utilize the cluster exactly as if we're logged into a node, except that it's remote. ??? :EN:- Working with remote Kubernetes clusters :FR:- Travailler avec des *clusters* distants .debug[[k8s/localkubeconfig.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/localkubeconfig.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-accessing-internal-services class: title Accessing internal services .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-controlling-a-kubernetes-cluster-remotely) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-2) | [Next part](#toc-accessing-the-api-with-kubectl-proxy) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Accessing internal services - When we are logged in on a cluster node, we can access internal services (by virtue of the Kubernetes network model: all nodes can reach all pods and services) - When we are accessing a remote cluster, things are different (generally, our local machine won't have access to the cluster's internal subnet) - How can we temporarily access a service without exposing it to everyone? -- - `kubectl proxy`: gives us access to the API, which includes a proxy for HTTP resources - `kubectl port-forward`: allows forwarding of TCP ports to arbitrary pods, services, ... .debug[[k8s/accessinternal.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/accessinternal.md)] --- ## Suspension of disbelief The labs and demos in this section assume that we have set up `kubectl` on our local machine in order to access a remote cluster. We will therefore show how to access services and pods of the remote cluster, from our local machine. You can also run these commands directly on the cluster (if you haven't installed and set up `kubectl` locally). Running commands locally will be less useful (since you could access services and pods directly), but keep in mind that these commands will work anywhere as long as you have installed and set up `kubectl` to communicate with your cluster. .debug[[k8s/accessinternal.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/accessinternal.md)] --- ## `kubectl proxy` in theory - Running `kubectl proxy` gives us access to the entire Kubernetes API - The API includes routes to proxy HTTP traffic - These routes look like the following: `/api/v1/namespaces/<namespace>/services/<service>/proxy` - We just add the URI to the end of the request, for instance: `/api/v1/namespaces/<namespace>/services/<service>/proxy/index.html` - We can access `services` and `pods` this way .debug[[k8s/accessinternal.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/accessinternal.md)] --- ## `kubectl proxy` in practice - Let's access the `webui` service through `kubectl proxy` .lab[ - Run an API proxy in the background: ```bash kubectl proxy & ``` - Access the `webui` service: ```bash curl localhost:8001/api/v1/namespaces/default/services/webui/proxy/index.html ``` - Terminate the proxy: ```bash kill %1 ``` ] .debug[[k8s/accessinternal.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/accessinternal.md)] --- ## `kubectl port-forward` in theory - What if we want to access a TCP service? - We can use `kubectl port-forward` instead - It will create a TCP relay to forward connections to a specific port (of a pod, service, deployment...) - The syntax is: `kubectl port-forward service/name_of_service local_port:remote_port` - If only one port number is specified, it is used for both local and remote ports .debug[[k8s/accessinternal.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/accessinternal.md)] --- ## `kubectl port-forward` in practice - Let's access our remote Redis server .lab[ - Forward connections from local port 10000 to remote port 6379: ```bash kubectl port-forward svc/redis 10000:6379 & ``` - Connect to the Redis server: ```bash telnet localhost 10000 ``` - Issue a few commands, e.g. `INFO server` then `QUIT` <!-- ```wait Connected to localhost``` ```keys INFO server``` ```key ^J``` ```keys QUIT``` ```key ^J``` --> - Terminate the port forwarder: ```bash kill %1 ``` ] ??? :EN:- Securely accessing internal services :FR:- Accès sécurisé aux services internes :T: Accessing internal services from our local machine :Q: What's the advantage of "kubectl port-forward" compared to a NodePort? :A: It can forward arbitrary protocols :A: It doesn't require Kubernetes API credentials :A: It offers deterministic load balancing (instead of random) :A: ✔️It doesn't expose the service to the public :Q: What's the security concept behind "kubectl port-forward"? :A: ✔️We authenticate with the Kubernetes API, and it forwards connections on our behalf :A: It detects our source IP address, and only allows connections coming from it :A: It uses end-to-end mTLS (mutual TLS) to authenticate our connections :A: There is no security (as long as it's running, anyone can connect from anywhere) .debug[[k8s/accessinternal.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/accessinternal.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-accessing-the-api-with-kubectl-proxy class: title Accessing the API with `kubectl proxy` .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-accessing-internal-services) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-2) | [Next part](#toc-exercise--local-cluster) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Accessing the API with `kubectl proxy` - The API requires us to authenticate.red[¹] - There are many authentication methods available, including: - TLS client certificates <br/> (that's what we've used so far) - HTTP basic password authentication <br/> (from a static file; not recommended) - various token mechanisms <br/> (detailed in the [documentation](https://kubernetes.io/docs/reference/access-authn-authz/authentication/#authentication-strategies)) .red[¹]OK, we lied. If you don't authenticate, you are considered to be user `system:anonymous`, which doesn't have any access rights by default. .debug[[k8s/kubectlproxy.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlproxy.md)] --- ## Accessing the API directly - Let's see what happens if we try to access the API directly with `curl` .lab[ - Retrieve the ClusterIP allocated to the `kubernetes` service: ```bash kubectl get svc kubernetes ``` - Replace the IP below and try to connect with `curl`: ```bash curl -k https://`10.96.0.1`/ ``` ] The API will tell us that user `system:anonymous` cannot access this path. .debug[[k8s/kubectlproxy.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlproxy.md)] --- ## Authenticating to the API If we wanted to talk to the API, we would need to: - extract our TLS key and certificate information from `~/.kube/config` (the information is in PEM format, encoded in base64) - use that information to present our certificate when connecting (for instance, with `openssl s_client -key ... -cert ... -connect ...`) - figure out exactly which credentials to use (once we start juggling multiple clusters) - change that whole process if we're using another authentication method 🤔 There has to be a better way! .debug[[k8s/kubectlproxy.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlproxy.md)] --- ## Using `kubectl proxy` for authentication - `kubectl proxy` runs a proxy in the foreground - This proxy lets us access the Kubernetes API without authentication (`kubectl proxy` adds our credentials on the fly to the requests) - This proxy lets us access the Kubernetes API over plain HTTP - This is a great tool to learn and experiment with the Kubernetes API - ... And for serious uses as well (suitable for one-shot scripts) - For unattended use, it's better to create a [service account](https://kubernetes.io/docs/tasks/configure-pod-container/configure-service-account/) .debug[[k8s/kubectlproxy.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlproxy.md)] --- ## Trying `kubectl proxy` - Let's start `kubectl proxy` and then do a simple request with `curl`! .lab[ - Start `kubectl proxy` in the background: ```bash kubectl proxy & ``` - Access the API's default route: ```bash curl localhost:8001 ``` <!-- ```wait /version``` ```key ^J``` --> - Terminate the proxy: ```bash kill %1 ``` ] The output is a list of available API routes. .debug[[k8s/kubectlproxy.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlproxy.md)] --- ## OpenAPI (fka Swagger) - The Kubernetes API serves an OpenAPI Specification (OpenAPI was formerly known as Swagger) - OpenAPI has many advantages (generate client library code, generate test code ...) - For us, this means we can explore the API with [Swagger UI](https://swagger.io/tools/swagger-ui/) (for instance with the [Swagger UI add-on for Firefox](https://addons.mozilla.org/en-US/firefox/addon/swagger-ui-ff/)) .debug[[k8s/kubectlproxy.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlproxy.md)] --- ## `kubectl proxy` is intended for local use - By default, the proxy listens on port 8001 (But this can be changed, or we can tell `kubectl proxy` to pick a port) - By default, the proxy binds to `127.0.0.1` (Making it unreachable from other machines, for security reasons) - By default, the proxy only accepts connections from: `^localhost$,^127\.0\.0\.1$,^\[::1\]$` - This is great when running `kubectl proxy` locally - Not-so-great when you want to connect to the proxy from a remote machine .debug[[k8s/kubectlproxy.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlproxy.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Running `kubectl proxy` on a remote machine - If we wanted to connect to the proxy from another machine, we would need to: - bind to `INADDR_ANY` instead of `127.0.0.1` - accept connections from any address - This is achieved with: ``` kubectl proxy --port=8888 --address=0.0.0.0 --accept-hosts=.* ``` .warning[Do not do this on a real cluster: it opens full unauthenticated access!] .debug[[k8s/kubectlproxy.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlproxy.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Security considerations - Running `kubectl proxy` openly is a huge security risk - It is slightly better to run the proxy where you need it (and copy credentials, e.g. `~/.kube/config`, to that place) - It is even better to use a limited account with reduced permissions .debug[[k8s/kubectlproxy.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlproxy.md)] --- ## Good to know ... - `kubectl proxy` also gives access to all internal services - Specifically, services are exposed as such: ``` /api/v1/namespaces/<namespace>/services/<service>/proxy ``` - We can use `kubectl proxy` to access an internal service in a pinch (or, for non HTTP services, `kubectl port-forward`) - This is not very useful when running `kubectl` directly on the cluster (since we could connect to the services directly anyway) - But it is very powerful as soon as you run `kubectl` from a remote machine .debug[[k8s/kubectlproxy.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/kubectlproxy.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-exercise--local-cluster class: title Exercise — Local Cluster .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-accessing-the-api-with-kubectl-proxy) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-2) | [Next part](#toc-scaling-our-demo-app) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Exercise — Local Cluster - We want to have our own local Kubernetes cluster (we can use Docker Desktop, KinD, minikube... anything will do!) - Then we want to run a copy of dockercoins on that cluster - We want to be able to connect to the web UI (we can expose the port, or use port-forward, or whatever) .debug[[exercises/localcluster-details.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/exercises/localcluster-details.md)] --- ## Goal - Be able to see the dockercoins web UI running on our local cluster .debug[[exercises/localcluster-details.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/exercises/localcluster-details.md)] --- ## Hints - On a Mac or Windows machine: the easiest solution is probably Docker Desktop - On a Linux machine: the easiest solution is probably KinD or k3d - To connect to the web UI: `kubectl port-forward` is probably the easiest solution .debug[[exercises/localcluster-details.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/exercises/localcluster-details.md)] --- ## Bonus - If you already have a local Kubernetes cluster: try to run another one! - Try to use another method than `kubectl port-forward` .debug[[exercises/localcluster-details.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/exercises/localcluster-details.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-scaling-our-demo-app class: title Scaling our demo app .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-exercise--local-cluster) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-3) | [Next part](#toc-daemon-sets) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Scaling our demo app - Our ultimate goal is to get more DockerCoins (i.e. increase the number of loops per second shown on the web UI) - Let's look at the architecture again:  - The loop is done in the worker; perhaps we could try adding more workers? .debug[[k8s/scalingdockercoins.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/scalingdockercoins.md)] --- ## Adding another worker - All we have to do is scale the `worker` Deployment .lab[ - Open a new terminal to keep an eye on our pods: ```bash kubectl get pods -w ``` <!-- ```wait RESTARTS``` ```tmux split-pane -h``` --> - Now, create more `worker` replicas: ```bash kubectl scale deployment worker --replicas=2 ``` ] After a few seconds, the graph in the web UI should show up. .debug[[k8s/scalingdockercoins.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/scalingdockercoins.md)] --- ## Adding more workers - If 2 workers give us 2x speed, what about 3 workers? .lab[ - Scale the `worker` Deployment further: ```bash kubectl scale deployment worker --replicas=3 ``` ] The graph in the web UI should go up again. (This is looking great! We're gonna be RICH!) .debug[[k8s/scalingdockercoins.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/scalingdockercoins.md)] --- ## Adding even more workers - Let's see if 10 workers give us 10x speed! .lab[ - Scale the `worker` Deployment to a bigger number: ```bash kubectl scale deployment worker --replicas=10 ``` <!-- ```key ^D``` ```key ^C``` --> ] -- The graph will peak at 10 hashes/second. (We can add as many workers as we want: we will never go past 10 hashes/second.) .debug[[k8s/scalingdockercoins.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/scalingdockercoins.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Didn't we briefly exceed 10 hashes/second? - It may *look like it*, because the web UI shows instant speed - The instant speed can briefly exceed 10 hashes/second - The average speed cannot - The instant speed can be biased because of how it's computed .debug[[k8s/scalingdockercoins.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/scalingdockercoins.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Why instant speed is misleading - The instant speed is computed client-side by the web UI - The web UI checks the hash counter once per second <br/> (and does a classic (h2-h1)/(t2-t1) speed computation) - The counter is updated once per second by the workers - These timings are not exact <br/> (e.g. the web UI check interval is client-side JavaScript) - Sometimes, between two web UI counter measurements, <br/> the workers are able to update the counter *twice* - During that cycle, the instant speed will appear to be much bigger <br/> (but it will be compensated by lower instant speed before and after) .debug[[k8s/scalingdockercoins.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/scalingdockercoins.md)] --- ## Why are we stuck at 10 hashes per second? - If this was high-quality, production code, we would have instrumentation (Datadog, Honeycomb, New Relic, statsd, Sumologic, ...) - It's not! - Perhaps we could benchmark our web services? (with tools like `ab`, or even simpler, `httping`) .debug[[k8s/scalingdockercoins.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/scalingdockercoins.md)] --- ## Benchmarking our web services - We want to check `hasher` and `rng` - We are going to use `httping` - It's just like `ping`, but using HTTP `GET` requests (it measures how long it takes to perform one `GET` request) - It's used like this: ``` httping [-c count] http://host:port/path ``` - Or even simpler: ``` httping ip.ad.dr.ess ``` - We will use `httping` on the ClusterIP addresses of our services .debug[[k8s/scalingdockercoins.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/scalingdockercoins.md)] --- ## Obtaining ClusterIP addresses - We can simply check the output of `kubectl get services` - Or do it programmatically, as in the example below .lab[ - Retrieve the IP addresses: ```bash HASHER=$(kubectl get svc hasher -o go-template={{.spec.clusterIP}}) RNG=$(kubectl get svc rng -o go-template={{.spec.clusterIP}}) ``` ] Now we can access the IP addresses of our services through `$HASHER` and `$RNG`. .debug[[k8s/scalingdockercoins.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/scalingdockercoins.md)] --- ## Checking `hasher` and `rng` response times .lab[ - Check the response times for both services: ```bash httping -c 3 $HASHER httping -c 3 $RNG ``` ] - `hasher` is fine (it should take a few milliseconds to reply) - `rng` is not (it should take about 700 milliseconds if there are 10 workers) - Something is wrong with `rng`, but ... what? ??? :EN:- Scaling up our demo app :FR:- *Scale up* de l'application de démo .debug[[k8s/scalingdockercoins.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/scalingdockercoins.md)] --- ## Let's draw hasty conclusions - The bottleneck seems to be `rng` - *What if* we don't have enough entropy and can't generate enough random numbers? - We need to scale out the `rng` service on multiple machines! Note: this is a fiction! We have enough entropy. But we need a pretext to scale out. (In fact, the code of `rng` uses `/dev/urandom`, which never runs out of entropy... <br/> ...and is [just as good as `/dev/random`](http://www.slideshare.net/PacSecJP/filippo-plain-simple-reality-of-entropy).) .debug[[shared/hastyconclusions.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/hastyconclusions.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-daemon-sets class: title Daemon sets .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-scaling-our-demo-app) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-3) | [Next part](#toc-labels-and-selectors) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Daemon sets - We want to scale `rng` in a way that is different from how we scaled `worker` - We want one (and exactly one) instance of `rng` per node - We *do not want* two instances of `rng` on the same node - We will do that with a *daemon set* .debug[[k8s/daemonset.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/daemonset.md)] --- ## Why not a deployment? - Can't we just do `kubectl scale deployment rng --replicas=...`? -- - Nothing guarantees that the `rng` containers will be distributed evenly - If we add nodes later, they will not automatically run a copy of `rng` - If we remove (or reboot) a node, one `rng` container will restart elsewhere (and we will end up with two instances `rng` on the same node) - By contrast, a daemon set will start one pod per node and keep it that way (as nodes are added or removed) .debug[[k8s/daemonset.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/daemonset.md)] --- ## Daemon sets in practice - Daemon sets are great for cluster-wide, per-node processes: - `kube-proxy` - `weave` (our overlay network) - monitoring agents - hardware management tools (e.g. SCSI/FC HBA agents) - etc. - They can also be restricted to run [only on some nodes](https://kubernetes.io/docs/concepts/workloads/controllers/daemonset/#running-pods-on-only-some-nodes) .debug[[k8s/daemonset.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/daemonset.md)] --- ## Creating a daemon set <!-- ##VERSION## --> - Unfortunately, as of Kubernetes 1.19, the CLI cannot create daemon sets -- - More precisely: it doesn't have a subcommand to create a daemon set -- - But any kind of resource can always be created by providing a YAML description: ```bash kubectl apply -f foo.yaml ``` -- - How do we create the YAML file for our daemon set? -- - option 1: [read the docs](https://kubernetes.io/docs/concepts/workloads/controllers/daemonset/#create-a-daemonset) -- - option 2: `vi` our way out of it .debug[[k8s/daemonset.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/daemonset.md)] --- ## Creating the YAML file for our daemon set - Let's start with the YAML file for the current `rng` resource .lab[ - Dump the `rng` resource in YAML: ```bash kubectl get deploy/rng -o yaml >rng.yml ``` - Edit `rng.yml` ] .debug[[k8s/daemonset.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/daemonset.md)] --- ## "Casting" a resource to another - What if we just changed the `kind` field? (It can't be that easy, right?) .lab[ - Change `kind: Deployment` to `kind: DaemonSet` <!-- ```bash vim rng.yml``` ```wait kind: Deployment``` ```keys /Deployment``` ```key ^J``` ```keys cwDaemonSet``` ```key ^[``` ] ```keys :wq``` ```key ^J``` --> - Save, quit - Try to create our new resource: ```bash kubectl apply -f rng.yml ``` <!-- ```wait error:``` --> ] -- We all knew this couldn't be that easy, right! .debug[[k8s/daemonset.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/daemonset.md)] --- ## Understanding the problem - The core of the error is: ``` error validating data: [ValidationError(DaemonSet.spec): unknown field "replicas" in io.k8s.api.extensions.v1beta1.DaemonSetSpec, ... ``` -- - *Obviously,* it doesn't make sense to specify a number of replicas for a daemon set -- - Workaround: fix the YAML - remove the `replicas` field - remove the `strategy` field (which defines the rollout mechanism for a deployment) - remove the `progressDeadlineSeconds` field (also used by the rollout mechanism) - remove the `status: {}` line at the end -- - Or, we could also ... .debug[[k8s/daemonset.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/daemonset.md)] --- ## Use the `--force`, Luke - We could also tell Kubernetes to ignore these errors and try anyway - The `--force` flag's actual name is `--validate=false` .lab[ - Try to load our YAML file and ignore errors: ```bash kubectl apply -f rng.yml --validate=false ``` ] -- 🎩✨🐇 -- Wait ... Now, can it be *that* easy? .debug[[k8s/daemonset.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/daemonset.md)] --- ## Checking what we've done - Did we transform our `deployment` into a `daemonset`? .lab[ - Look at the resources that we have now: ```bash kubectl get all ``` ] -- We have two resources called `rng`: - the *deployment* that was existing before - the *daemon set* that we just created We also have one too many pods. <br/> (The pod corresponding to the *deployment* still exists.) .debug[[k8s/daemonset.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/daemonset.md)] --- ## `deploy/rng` and `ds/rng` - You can have different resource types with the same name (i.e. a *deployment* and a *daemon set* both named `rng`) - We still have the old `rng` *deployment* ``` NAME DESIRED CURRENT UP-TO-DATE AVAILABLE AGE deployment.apps/rng 1 1 1 1 18m ``` - But now we have the new `rng` *daemon set* as well ``` NAME DESIRED CURRENT READY UP-TO-DATE AVAILABLE NODE SELECTOR AGE daemonset.apps/rng 2 2 2 2 2 <none> 9s ``` .debug[[k8s/daemonset.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/daemonset.md)] --- ## Too many pods - If we check with `kubectl get pods`, we see: - *one pod* for the deployment (named `rng-xxxxxxxxxx-yyyyy`) - *one pod per node* for the daemon set (named `rng-zzzzz`) ``` NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE rng-54f57d4d49-7pt82 1/1 Running 0 11m rng-b85tm 1/1 Running 0 25s rng-hfbrr 1/1 Running 0 25s [...] ``` -- The daemon set created one pod per node, except on the master node. The master node has [taints](https://kubernetes.io/docs/concepts/configuration/taint-and-toleration/) preventing pods from running there. (To schedule a pod on this node anyway, the pod will require appropriate [tolerations](https://kubernetes.io/docs/concepts/configuration/taint-and-toleration/).) .footnote[(Off by one? We don't run these pods on the node hosting the control plane.)] .debug[[k8s/daemonset.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/daemonset.md)] --- ## Is this working? - Look at the web UI -- - The graph should now go above 10 hashes per second! -- - It looks like the newly created pods are serving traffic correctly - How and why did this happen? (We didn't do anything special to add them to the `rng` service load balancer!) .debug[[k8s/daemonset.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/daemonset.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-labels-and-selectors class: title Labels and selectors .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-daemon-sets) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-3) | [Next part](#toc-rolling-updates) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Labels and selectors - The `rng` *service* is load balancing requests to a set of pods - That set of pods is defined by the *selector* of the `rng` service .lab[ - Check the *selector* in the `rng` service definition: ```bash kubectl describe service rng ``` ] - The selector is `app=rng` - It means "all the pods having the label `app=rng`" (They can have additional labels as well, that's OK!) .debug[[k8s/daemonset.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/daemonset.md)] --- ## Selector evaluation - We can use selectors with many `kubectl` commands - For instance, with `kubectl get`, `kubectl logs`, `kubectl delete` ... and more .lab[ - Get the list of pods matching selector `app=rng`: ```bash kubectl get pods -l app=rng kubectl get pods --selector app=rng ``` ] But ... why do these pods (in particular, the *new* ones) have this `app=rng` label? .debug[[k8s/daemonset.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/daemonset.md)] --- ## Where do labels come from? - When we create a deployment with `kubectl create deployment rng`, <br/>this deployment gets the label `app=rng` - The replica sets created by this deployment also get the label `app=rng` - The pods created by these replica sets also get the label `app=rng` - When we created the daemon set from the deployment, we re-used the same spec - Therefore, the pods created by the daemon set get the same labels .footnote[Note: when we use `kubectl run stuff`, the label is `run=stuff` instead.] .debug[[k8s/daemonset.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/daemonset.md)] --- ## Updating load balancer configuration - We would like to remove a pod from the load balancer - What would happen if we removed that pod, with `kubectl delete pod ...`? -- It would be re-created immediately (by the replica set or the daemon set) -- - What would happen if we removed the `app=rng` label from that pod? -- It would *also* be re-created immediately -- Why?!? .debug[[k8s/daemonset.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/daemonset.md)] --- ## Selectors for replica sets and daemon sets - The "mission" of a replica set is: "Make sure that there is the right number of pods matching this spec!" - The "mission" of a daemon set is: "Make sure that there is a pod matching this spec on each node!" -- - *In fact,* replica sets and daemon sets do not check pod specifications - They merely have a *selector*, and they look for pods matching that selector - Yes, we can fool them by manually creating pods with the "right" labels - Bottom line: if we remove our `app=rng` label ... ... The pod "disappears" for its parent, which re-creates another pod to replace it .debug[[k8s/daemonset.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/daemonset.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Isolation of replica sets and daemon sets - Since both the `rng` daemon set and the `rng` replica set use `app=rng` ... ... Why don't they "find" each other's pods? -- - *Replica sets* have a more specific selector, visible with `kubectl describe` (It looks like `app=rng,pod-template-hash=abcd1234`) - *Daemon sets* also have a more specific selector, but it's invisible (It looks like `app=rng,controller-revision-hash=abcd1234`) - As a result, each controller only "sees" the pods it manages .debug[[k8s/daemonset.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/daemonset.md)] --- ## Removing a pod from the load balancer - Currently, the `rng` service is defined by the `app=rng` selector - The only way to remove a pod is to remove or change the `app` label - ... But that will cause another pod to be created instead! - What's the solution? -- - We need to change the selector of the `rng` service! - Let's add another label to that selector (e.g. `active=yes`) .debug[[k8s/daemonset.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/daemonset.md)] --- ## Selectors with multiple labels - If a selector specifies multiple labels, they are understood as a logical *AND* (in other words: the pods must match all the labels) - We cannot have a logical *OR* (e.g. `app=api AND (release=prod OR release=preprod)`) - We can, however, apply as many extra labels as we want to our pods: - use selector `app=api AND prod-or-preprod=yes` - add `prod-or-preprod=yes` to both sets of pods - We will see later that in other places, we can use more advanced selectors .debug[[k8s/daemonset.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/daemonset.md)] --- ## The plan 1. Add the label `active=yes` to all our `rng` pods 2. Update the selector for the `rng` service to also include `active=yes` 3. Toggle traffic to a pod by manually adding/removing the `active` label 4. Profit! *Note: if we swap steps 1 and 2, it will cause a short service disruption, because there will be a period of time during which the service selector won't match any pod. During that time, requests to the service will time out. By doing things in the order above, we guarantee that there won't be any interruption.* .debug[[k8s/daemonset.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/daemonset.md)] --- ## Adding labels to pods - We want to add the label `active=yes` to all pods that have `app=rng` - We could edit each pod one by one with `kubectl edit` ... - ... Or we could use `kubectl label` to label them all - `kubectl label` can use selectors itself .lab[ - Add `active=yes` to all pods that have `app=rng`: ```bash kubectl label pods -l app=rng active=yes ``` ] .debug[[k8s/daemonset.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/daemonset.md)] --- ## Updating the service selector - We need to edit the service specification - Reminder: in the service definition, we will see `app: rng` in two places - the label of the service itself (we don't need to touch that one) - the selector of the service (that's the one we want to change) .lab[ - Update the service to add `active: yes` to its selector: ```bash kubectl edit service rng ``` <!-- ```wait Please edit the object below``` ```keys /app: rng``` ```key ^J``` ```keys noactive: yes``` ```key ^[``` ] ```keys :wq``` ```key ^J``` --> ] -- ... And then we get *the weirdest error ever.* Why? .debug[[k8s/daemonset.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/daemonset.md)] --- ## When the YAML parser is being too smart - YAML parsers try to help us: - `xyz` is the string `"xyz"` - `42` is the integer `42` - `yes` is the boolean value `true` - If we want the string `"42"` or the string `"yes"`, we have to quote them - So we have to use `active: "yes"` .footnote[For a good laugh: if we had used "ja", "oui", "si" ... as the value, it would have worked!] .debug[[k8s/daemonset.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/daemonset.md)] --- ## Updating the service selector, take 2 .lab[ - Update the YAML manifest of the service - Add `active: "yes"` to its selector <!-- ```wait Please edit the object below``` ```keys /yes``` ```key ^J``` ```keys cw"yes"``` ```key ^[``` ] ```keys :wq``` ```key ^J``` --> ] This time it should work! If we did everything correctly, the web UI shouldn't show any change. .debug[[k8s/daemonset.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/daemonset.md)] --- ## Updating labels - We want to disable the pod that was created by the deployment - All we have to do, is remove the `active` label from that pod - To identify that pod, we can use its name - ... Or rely on the fact that it's the only one with a `pod-template-hash` label - Good to know: - `kubectl label ... foo=` doesn't remove a label (it sets it to an empty string) - to remove label `foo`, use `kubectl label ... foo-` - to change an existing label, we would need to add `--overwrite` .debug[[k8s/daemonset.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/daemonset.md)] --- ## Removing a pod from the load balancer .lab[ - In one window, check the logs of that pod: ```bash POD=$(kubectl get pod -l app=rng,pod-template-hash -o name) kubectl logs --tail 1 --follow $POD ``` (We should see a steady stream of HTTP logs) <!-- ```wait HTTP/1.1``` ```tmux split-pane -v``` --> - In another window, remove the label from the pod: ```bash kubectl label pod -l app=rng,pod-template-hash active- ``` (The stream of HTTP logs should stop immediately) <!-- ```key ^D``` ```key ^C``` --> ] There might be a slight change in the web UI (since we removed a bit of capacity from the `rng` service). If we remove more pods, the effect should be more visible. .debug[[k8s/daemonset.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/daemonset.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Updating the daemon set - If we scale up our cluster by adding new nodes, the daemon set will create more pods - These pods won't have the `active=yes` label - If we want these pods to have that label, we need to edit the daemon set spec - We can do that with e.g. `kubectl edit daemonset rng` .debug[[k8s/daemonset.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/daemonset.md)] --- class: extra-details ## We've put resources in your resources - Reminder: a daemon set is a resource that creates more resources! - There is a difference between: - the label(s) of a resource (in the `metadata` block in the beginning) - the selector of a resource (in the `spec` block) - the label(s) of the resource(s) created by the first resource (in the `template` block) - We would need to update the selector and the template (metadata labels are not mandatory) - The template must match the selector (i.e. the resource will refuse to create resources that it will not select) .debug[[k8s/daemonset.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/daemonset.md)] --- ## Labels and debugging - When a pod is misbehaving, we can delete it: another one will be recreated - But we can also change its labels - It will be removed from the load balancer (it won't receive traffic anymore) - Another pod will be recreated immediately - But the problematic pod is still here, and we can inspect and debug it - We can even re-add it to the rotation if necessary (Very useful to troubleshoot intermittent and elusive bugs) .debug[[k8s/daemonset.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/daemonset.md)] --- ## Labels and advanced rollout control - Conversely, we can add pods matching a service's selector - These pods will then receive requests and serve traffic - Examples: - one-shot pod with all debug flags enabled, to collect logs - pods created automatically, but added to rotation in a second step <br/> (by setting their label accordingly) - This gives us building blocks for canary and blue/green deployments .debug[[k8s/daemonset.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/daemonset.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Advanced label selectors - As indicated earlier, service selectors are limited to a `AND` - But in many other places in the Kubernetes API, we can use complex selectors (e.g. Deployment, ReplicaSet, DaemonSet, NetworkPolicy ...) - These allow extra operations; specifically: - checking for presence (or absence) of a label - checking if a label is (or is not) in a given set - Relevant documentation: [Service spec](https://kubernetes.io/docs/reference/generated/kubernetes-api/v1.19/#servicespec-v1-core), [LabelSelector spec](https://kubernetes.io/docs/reference/generated/kubernetes-api/v1.19/#labelselector-v1-meta), [label selector doc](https://kubernetes.io/docs/concepts/overview/working-with-objects/labels/#label-selectors) .debug[[k8s/daemonset.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/daemonset.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Example of advanced selector ```yaml theSelector: matchLabels: app: portal component: api matchExpressions: - key: release operator: In values: [ production, preproduction ] - key: signed-off-by operator: Exists ``` This selector matches pods that meet *all* the indicated conditions. `operator` can be `In`, `NotIn`, `Exists`, `DoesNotExist`. A `nil` selector matches *nothing*, a `{}` selector matches *everything*. <br/> (Because that means "match all pods that meet at least zero condition".) .debug[[k8s/daemonset.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/daemonset.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Services and Endpoints - Each Service has a corresponding Endpoints resource (see `kubectl get endpoints` or `kubectl get ep`) - That Endpoints resource is used by various controllers (e.g. `kube-proxy` when setting up `iptables` rules for ClusterIP services) - These Endpoints are populated (and updated) with the Service selector - We can update the Endpoints manually, but our changes will get overwritten - ... Except if the Service selector is empty! .debug[[k8s/daemonset.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/daemonset.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Empty Service selector - If a service selector is empty, Endpoints don't get updated automatically (but we can still set them manually) - This lets us create Services pointing to arbitrary destinations (potentially outside the cluster; or things that are not in pods) - Another use-case: the `kubernetes` service in the `default` namespace (its Endpoints are maintained automatically by the API server) ??? :EN:- Scaling with Daemon Sets :FR:- Utilisation de Daemon Sets .debug[[k8s/daemonset.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/daemonset.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-rolling-updates class: title Rolling updates .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-labels-and-selectors) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-3) | [Next part](#toc-healthchecks) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Rolling updates - How should we update a running application? - Strategy 1: delete old version, then deploy new version (not great, because it obviously provokes downtime!) - Strategy 2: deploy new version, then delete old version (uses a lot of resources; also how do we shift traffic?) - Strategy 3: replace running pods one at a time (sounds interesting; and good news, Kubernetes does it for us!) .debug[[k8s/rollout.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/rollout.md)] --- ## Rolling updates - With rolling updates, when a Deployment is updated, it happens progressively - The Deployment controls multiple Replica Sets - Each Replica Set is a group of identical Pods (with the same image, arguments, parameters ...) - During the rolling update, we have at least two Replica Sets: - the "new" set (corresponding to the "target" version) - at least one "old" set - We can have multiple "old" sets (if we start another update before the first one is done) .debug[[k8s/rollout.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/rollout.md)] --- ## Update strategy - Two parameters determine the pace of the rollout: `maxUnavailable` and `maxSurge` - They can be specified in absolute number of pods, or percentage of the `replicas` count - At any given time ... - there will always be at least `replicas`-`maxUnavailable` pods available - there will never be more than `replicas`+`maxSurge` pods in total - there will therefore be up to `maxUnavailable`+`maxSurge` pods being updated - We have the possibility of rolling back to the previous version <br/>(if the update fails or is unsatisfactory in any way) .debug[[k8s/rollout.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/rollout.md)] --- ## Checking current rollout parameters - Recall how we build custom reports with `kubectl` and `jq`: .lab[ - Show the rollout plan for our deployments: ```bash kubectl get deploy -o json | jq ".items[] | {name:.metadata.name} + .spec.strategy.rollingUpdate" ``` ] .debug[[k8s/rollout.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/rollout.md)] --- ## Rolling updates in practice - As of Kubernetes 1.8, we can do rolling updates with: `deployments`, `daemonsets`, `statefulsets` - Editing one of these resources will automatically result in a rolling update - Rolling updates can be monitored with the `kubectl rollout` subcommand .debug[[k8s/rollout.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/rollout.md)] --- ## Rolling out the new `worker` service .lab[ - Let's monitor what's going on by opening a few terminals, and run: ```bash kubectl get pods -w kubectl get replicasets -w kubectl get deployments -w ``` <!-- ```wait NAME``` ```key ^C``` --> - Update `worker` either with `kubectl edit`, or by running: ```bash kubectl set image deploy worker worker=dockercoins/worker:v0.2 ``` ] -- That rollout should be pretty quick. What shows in the web UI? .debug[[k8s/rollout.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/rollout.md)] --- ## Give it some time - At first, it looks like nothing is happening (the graph remains at the same level) - According to `kubectl get deploy -w`, the `deployment` was updated really quickly - But `kubectl get pods -w` tells a different story - The old `pods` are still here, and they stay in `Terminating` state for a while - Eventually, they are terminated; and then the graph decreases significantly - This delay is due to the fact that our worker doesn't handle signals - Kubernetes sends a "polite" shutdown request to the worker, which ignores it - After a grace period, Kubernetes gets impatient and kills the container (The grace period is 30 seconds, but [can be changed](https://kubernetes.io/docs/concepts/workloads/pods/pod/#termination-of-pods) if needed) .debug[[k8s/rollout.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/rollout.md)] --- ## Rolling out something invalid - What happens if we make a mistake? .lab[ - Update `worker` by specifying a non-existent image: ```bash kubectl set image deploy worker worker=dockercoins/worker:v0.3 ``` - Check what's going on: ```bash kubectl rollout status deploy worker ``` <!-- ```wait Waiting for deployment``` ```key ^C``` --> ] -- Our rollout is stuck. However, the app is not dead. (After a minute, it will stabilize to be 20-25% slower.) .debug[[k8s/rollout.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/rollout.md)] --- ## What's going on with our rollout? - Why is our app a bit slower? - Because `MaxUnavailable=25%` ... So the rollout terminated 2 replicas out of 10 available - Okay, but why do we see 5 new replicas being rolled out? - Because `MaxSurge=25%` ... So in addition to replacing 2 replicas, the rollout is also starting 3 more - It rounded down the number of MaxUnavailable pods conservatively, <br/> but the total number of pods being rolled out is allowed to be 25+25=50% .debug[[k8s/rollout.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/rollout.md)] --- class: extra-details ## The nitty-gritty details - We start with 10 pods running for the `worker` deployment - Current settings: MaxUnavailable=25% and MaxSurge=25% - When we start the rollout: - two replicas are taken down (as per MaxUnavailable=25%) - two others are created (with the new version) to replace them - three others are created (with the new version) per MaxSurge=25%) - Now we have 8 replicas up and running, and 5 being deployed - Our rollout is stuck at this point! .debug[[k8s/rollout.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/rollout.md)] --- ## Checking the dashboard during the bad rollout If you didn't deploy the Kubernetes dashboard earlier, just skip this slide. .lab[ - Connect to the dashboard that we deployed earlier - Check that we have failures in Deployments, Pods, and Replica Sets - Can we see the reason for the failure? ] .debug[[k8s/rollout.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/rollout.md)] --- ## Recovering from a bad rollout - We could push some `v0.3` image (the pod retry logic will eventually catch it and the rollout will proceed) - Or we could invoke a manual rollback .lab[ <!-- ```key ^C``` --> - Cancel the deployment and wait for the dust to settle: ```bash kubectl rollout undo deploy worker kubectl rollout status deploy worker ``` ] .debug[[k8s/rollout.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/rollout.md)] --- ## Rolling back to an older version - We reverted to `v0.2` - But this version still has a performance problem - How can we get back to the previous version? .debug[[k8s/rollout.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/rollout.md)] --- ## Multiple "undos" - What happens if we try `kubectl rollout undo` again? .lab[ - Try it: ```bash kubectl rollout undo deployment worker ``` - Check the web UI, the list of pods ... ] 🤔 That didn't work. .debug[[k8s/rollout.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/rollout.md)] --- ## Multiple "undos" don't work - If we see successive versions as a stack: - `kubectl rollout undo` doesn't "pop" the last element from the stack - it copies the N-1th element to the top - Multiple "undos" just swap back and forth between the last two versions! .lab[ - Go back to v0.2 again: ```bash kubectl rollout undo deployment worker ``` ] .debug[[k8s/rollout.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/rollout.md)] --- ## In this specific scenario - Our version numbers are easy to guess - What if we had used git hashes? - What if we had changed other parameters in the Pod spec? .debug[[k8s/rollout.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/rollout.md)] --- ## Listing versions - We can list successive versions of a Deployment with `kubectl rollout history` .lab[ - Look at our successive versions: ```bash kubectl rollout history deployment worker ``` ] We don't see *all* revisions. We might see something like 1, 4, 5. (Depending on how many "undos" we did before.) .debug[[k8s/rollout.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/rollout.md)] --- ## Explaining deployment revisions - These revisions correspond to our Replica Sets - This information is stored in the Replica Set annotations .lab[ - Check the annotations for our replica sets: ```bash kubectl describe replicasets -l app=worker | grep -A3 ^Annotations ``` ] .debug[[k8s/rollout.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/rollout.md)] --- class: extra-details ## What about the missing revisions? - The missing revisions are stored in another annotation: `deployment.kubernetes.io/revision-history` - These are not shown in `kubectl rollout history` - We could easily reconstruct the full list with a script (if we wanted to!) .debug[[k8s/rollout.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/rollout.md)] --- ## Rolling back to an older version - `kubectl rollout undo` can work with a revision number .lab[ - Roll back to the "known good" deployment version: ```bash kubectl rollout undo deployment worker --to-revision=1 ``` - Check the web UI or the list of pods ] .debug[[k8s/rollout.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/rollout.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Changing rollout parameters - We want to: - revert to `v0.1` - be conservative on availability (always have desired number of available workers) - go slow on rollout speed (update only one pod at a time) - give some time to our workers to "warm up" before starting more The corresponding changes can be expressed in the following YAML snippet: .small[ ```yaml spec: template: spec: containers: - name: worker image: dockercoins/worker:v0.1 strategy: rollingUpdate: maxUnavailable: 0 maxSurge: 1 minReadySeconds: 10 ``` ] .debug[[k8s/rollout.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/rollout.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Applying changes through a YAML patch - We could use `kubectl edit deployment worker` - But we could also use `kubectl patch` with the exact YAML shown before .lab[ .small[ - Apply all our changes and wait for them to take effect: ```bash kubectl patch deployment worker -p " spec: template: spec: containers: - name: worker image: dockercoins/worker:v0.1 strategy: rollingUpdate: maxUnavailable: 0 maxSurge: 1 minReadySeconds: 10 " kubectl rollout status deployment worker kubectl get deploy -o json worker | jq "{name:.metadata.name} + .spec.strategy.rollingUpdate" ``` ] ] ??? :EN:- Rolling updates :EN:- Rolling back a bad deployment :FR:- Mettre à jour un déploiement :FR:- Concept de *rolling update* et *rollback* :FR:- Paramétrer la vitesse de déploiement .debug[[k8s/rollout.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/rollout.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-healthchecks class: title Healthchecks .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-rolling-updates) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-3) | [Next part](#toc-the-kubernetes-dashboard) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Healthchecks - Containers can have *healthchecks* (also called "probes") - There are three kinds of healthchecks, corresponding to different use-cases: `startupProbe`, `readinessProbe`, `livenessProbe` - These healthchecks are optional (we can use none, all, or some of them) - Different probes are available: HTTP GET, TCP connection, arbitrary program execution, GRPC - All these probes have a binary result (success/failure) - Probes that aren't defined will default to a "success" result .debug[[k8s/healthchecks.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/healthchecks.md)] --- ## Use-cases in brief *My container takes a long time to boot before being able to serve traffic.* → use a `startupProbe` (but often a `readinessProbe` can also do the job) *Sometimes, my container is unavailable or overloaded, and needs to e.g. be taken temporarily out of load balancer rotation.* → use a `readinessProbe` *Sometimes, my container enters a broken state which can only be fixed by a restart.* → use a `livenessProbe` .debug[[k8s/healthchecks.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/healthchecks.md)] --- ## Liveness probes *This container is dead, we don't know how to fix it, other than restarting it.* - Check if the container is dead or alive - If Kubernetes determines that the container is dead: - it terminates the container gracefully - it restarts the container (unless the Pod's `restartPolicy` is `Never`) - With the default parameters, it takes: - up to 30 seconds to determine that the container is dead - up to 30 seconds to terminate it .debug[[k8s/healthchecks.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/healthchecks.md)] --- ## When to use a liveness probe - To detect failures that can't be recovered - deadlocks (causing all requests to time out) - internal corruption (causing all requests to error) - Anything where our incident response would be "just restart/reboot it" .debug[[k8s/healthchecks.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/healthchecks.md)] --- ## Liveness probes gotchas .warning[**Do not** use liveness probes for problems that can't be fixed by a restart] - Otherwise we just restart our pods for no reason, creating useless load .warning[**Do not** depend on other services within a liveness probe] - Otherwise we can experience cascading failures (example: web server liveness probe that makes a requests to a database) .warning[**Make sure** that liveness probes respond quickly] - The default probe timeout is 1 second (this can be tuned!) - If the probe takes longer than that, it will eventually cause a restart .debug[[k8s/healthchecks.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/healthchecks.md)] --- ## Readiness probes *Sometimes, my container "needs a break".* - Check if the container is ready or not - If the container is not ready, its Pod is not ready - If the Pod belongs to a Service, it is removed from its Endpoints (it stops receiving new connections but existing ones are not affected) - If there is a rolling update in progress, it might pause (Kubernetes will try to respect the MaxUnavailable parameter) - As soon as the readiness probe suceeds again, everything goes back to normal .debug[[k8s/healthchecks.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/healthchecks.md)] --- ## When to use a readiness probe - To indicate failure due to an external cause - database is down or unreachable - mandatory auth or other backend service unavailable - To indicate temporary failure or unavailability - runtime is busy doing garbage collection or (re)loading data - application can only service *N* parallel connections - new connections will be directed to other Pods .debug[[k8s/healthchecks.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/healthchecks.md)] --- ## Startup probes *My container takes a long time to boot before being able to serve traffic.* - After creating a container, Kubernetes runs its startup probe - The container will be considered "unhealthy" until the probe succeeds - As long as the container is "unhealthy", its Pod...: - is not added to Services' endpoints - is not considered as "available" for rolling update purposes - Readiness and liveness probes are enabled *after* startup probe reports success (if there is no startup probe, readiness and liveness probes are enabled right away) .debug[[k8s/healthchecks.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/healthchecks.md)] --- ## When to use a startup probe - For containers that take a long time to start (more than 30 seconds) - Especially if that time can vary a lot (e.g. fast in dev, slow in prod, or the other way around) .debug[[k8s/healthchecks.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/healthchecks.md)] --- ## Startup probes gotchas - When defining a `startupProbe`, we almost always want to adjust its parameters (specifically, its `failureThreshold` - this is explained in next slide) - Otherwise, if the container fails to start within 30 seconds... *Kubernetes terminates the container and restarts it!* - Sometimes, it's easier/simpler to use a `readinessProbe` instead (except when also using a `livenessProbe`) .debug[[k8s/healthchecks.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/healthchecks.md)] --- ## Timing and thresholds - Probes are executed at intervals of `periodSeconds` (default: 10) - The timeout for a probe is set with `timeoutSeconds` (default: 1) .warning[If a probe takes longer than that, it is considered as a FAIL] .warning[For liveness probes **and startup probes** this terminates and restarts the container] - A probe is considered successful after `successThreshold` successes (default: 1) - A probe is considered failing after `failureThreshold` failures (default: 3) - All these parameters can be set independently for each probe .debug[[k8s/healthchecks.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/healthchecks.md)] --- class: extra-details ## `initialDelaySeconds` - A probe can have an `initialDelaySeconds` parameter (default: 0) - Kubernetes will wait that amount of time before running the probe for the first time - It is generally better to use a `startupProbe` instead (but this parameter did exist before startup probes were implemented) .debug[[k8s/healthchecks.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/healthchecks.md)] --- class: extra-details ## `readinessProbe` vs `startupProbe` - A lot of blog posts / documentations / tutorials recommend readiness probes... - ...even in scenarios where a startup probe would seem more appropriate! - This is because startup probes are relatively recent (they reached GA status in Kubernetes 1.20) - When there is no `livenessProbe`, using a `readinessProbe` is simpler: - a `startupProbe` generally requires to change the `failureThreshold` - a `startupProbe` generally also requires a `readinessProbe` - a single `readinessProbe` can fulfill both roles .debug[[k8s/healthchecks.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/healthchecks.md)] --- ## Different types of probes - Kubernetes supports the following mechanisms: - `exec` (arbitrary program execution) - `httpGet` (HTTP GET request) - `tcpSocket` (check if a TCP port is accepting connections) - `grpc` (standard [GRPC Health Checking Protocol][grpc]) - All probes give binary results ("it works" or "it doesn't") - Let's see the specific details for each of them! [grpc]: https://grpc.github.io/grpc/core/md_doc_health-checking.html .debug[[k8s/healthchecks.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/healthchecks.md)] --- ## `exec` - Runs an arbitrary program *inside* the container (like with `kubectl exec` or `docker exec`) - The program must be available in the container image - Kubernetes uses the exit status of the program (standard UNIX convention: 0 = success, anything else = failure) .debug[[k8s/healthchecks.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/healthchecks.md)] --- ## `exec` example When the worker is ready, it should create `/tmp/ready`. <br/> The following probe will give it 5 minutes to do so. ```yaml apiVersion: v1 kind: Pod metadata: name: queueworker spec: containers: - name: worker image: myregistry.../worker:v1.0 startupProbe: exec: command: - test - -f - /tmp/ready failureThreshold: 30 ``` .debug[[k8s/healthchecks.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/healthchecks.md)] --- ## Using shell constructs - If we want to use pipes, conditionals, etc. we should invoke a shell - Example: ```yaml exec: command: - sh - -c - "curl http://localhost:5000/status | jq .ready | grep true" ``` .debug[[k8s/healthchecks.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/healthchecks.md)] --- ## `httpGet` - Make an HTTP GET request to the container - The request will be made by Kubelet (doesn't require extra binaries in the container image) - `port` must be specified - `path` and extra `httpHeaders` can be specified optionally - Kubernetes uses HTTP status code of the response: - 200-399 = success - anything else = failure .debug[[k8s/healthchecks.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/healthchecks.md)] --- ## `httpGet` example The following liveness probe restarts the container if it stops responding on `/healthz`: ```yaml apiVersion: v1 kind: Pod metadata: name: frontend spec: containers: - name: frontend image: myregistry.../frontend:v1.0 livenessProbe: httpGet: port: 80 path: /healthz ``` .debug[[k8s/healthchecks.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/healthchecks.md)] --- ## `tcpSocket` - Kubernetes checks if the indicated TCP port accepts connections - There is no additional check .warning[It's quite possible for a process to be broken, but still accept TCP connections!] .debug[[k8s/healthchecks.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/healthchecks.md)] --- ## `grpc` <!-- ##VERSION## --> - Available in beta since Kubernetes 1.24 - Leverages standard [GRPC Health Checking Protocol][grpc] [grpc]: https://grpc.github.io/grpc/core/md_doc_health-checking.html .debug[[k8s/healthchecks.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/healthchecks.md)] --- ## Best practices for healthchecks - Readiness probes are almost always beneficial - don't hesitate to add them early! - we can even make them *mandatory* - Be more careful with liveness and startup probes - they aren't always necessary - they can even cause harm .debug[[k8s/healthchecks.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/healthchecks.md)] --- ## Readiness probes - Almost always beneficial - Exceptions: - web service that doesn't have a dedicated "health" or "ping" route - ...and all requests are "expensive" (e.g. lots of external calls) .debug[[k8s/healthchecks.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/healthchecks.md)] --- ## Liveness probes - If we're not careful, we end up restarting containers for no reason (which can cause additional load on the cluster, cascading failures, data loss, etc.) - Suggestion: - don't add liveness probes immediately - wait until you have a bit of production experience with that code - then add narrow-scoped healthchecks to detect specific failure modes - Readiness and liveness probes should be different (different check *or* different timeouts *or* different thresholds) .debug[[k8s/healthchecks.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/healthchecks.md)] --- ## Startup probes - Only beneficial for containers that need a long time to start (more than 30 seconds) - If there is no liveness probe, it's simpler to just use a readiness probe (since we probably want to have a readiness probe anyway) - In other words, startup probes are useful in one situation: *we have a liveness probe, AND the container needs a lot of time to start* - Don't forget to change the `failureThreshold` (otherwise the container will fail to start and be killed) .debug[[k8s/healthchecks.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/healthchecks.md)] --- ## Recap of the gotchas - The default timeout is 1 second - if a probe takes longer than 1 second to reply, Kubernetes considers that it fails - this can be changed by setting the `timeoutSeconds` parameter <br/>(or refactoring the probe) - Liveness probes should not be influenced by the state of external services - Liveness probes and readiness probes should have different paramters - For startup probes, remember to increase the `failureThreshold` .debug[[k8s/healthchecks.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/healthchecks.md)] --- ## Healthchecks for workers (In that context, worker = process that doesn't accept connections) - A relatively easy solution is to use files - For a startup or readiness probe: - worker creates `/tmp/ready` when it's ready - probe checks the existence of `/tmp/ready` - For a liveness probe: - worker touches `/tmp/alive` regularly <br/>(e.g. just before starting to work on a job) - probe checks that the timestamp on `/tmp/alive` is recent - if the timestamp is old, it means that the worker is stuck - Sometimes it can also make sense to embed a web server in the worker ??? :EN:- Using healthchecks to improve availability :FR:- Utiliser des *healthchecks* pour améliorer la disponibilité .debug[[k8s/healthchecks.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/healthchecks.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-the-kubernetes-dashboard class: title The Kubernetes dashboard .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-healthchecks) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-3) | [Next part](#toc-security-implications-of-kubectl-apply) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # The Kubernetes dashboard - Kubernetes resources can also be viewed with a web dashboard - Dashboard users need to authenticate (typically with a token) - The dashboard should be exposed over HTTPS (to prevent interception of the aforementioned token) - Ideally, this requires obtaining a proper TLS certificate (for instance, with Let's Encrypt) .debug[[k8s/dashboard.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/dashboard.md)] --- ## Three ways to install the dashboard - Our `k8s` directory has no less than three manifests! - `dashboard-recommended.yaml` (purely internal dashboard; user must be created manually) - `dashboard-with-token.yaml` (dashboard exposed with NodePort; creates an admin user for us) - `dashboard-insecure.yaml` aka *YOLO* (dashboard exposed over HTTP; gives root access to anonymous users) .debug[[k8s/dashboard.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/dashboard.md)] --- ## `dashboard-insecure.yaml` - This will allow anyone to deploy anything on your cluster (without any authentication whatsoever) - **Do not** use this, except maybe on a local cluster (or a cluster that you will destroy a few minutes later) - On "normal" clusters, use `dashboard-with-token.yaml` instead! .debug[[k8s/dashboard.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/dashboard.md)] --- ## What's in the manifest? - The dashboard itself - An HTTP/HTTPS unwrapper (using `socat`) - The guest/admin account .lab[ - Create all the dashboard resources, with the following command: ```bash kubectl apply -f ~/container.training/k8s/dashboard-insecure.yaml ``` ] .debug[[k8s/dashboard.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/dashboard.md)] --- ## Connecting to the dashboard .lab[ - Check which port the dashboard is on: ```bash kubectl get svc dashboard ``` ] You'll want the `3xxxx` port. .lab[ - Connect to http://oneofournodes:3xxxx/ <!-- ```open http://node1:3xxxx/``` --> ] The dashboard will then ask you which authentication you want to use. .debug[[k8s/dashboard.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/dashboard.md)] --- ## Dashboard authentication - We have three authentication options at this point: - token (associated with a role that has appropriate permissions) - kubeconfig (e.g. using the `~/.kube/config` file from `node1`) - "skip" (use the dashboard "service account") - Let's use "skip": we're logged in! -- .warning[Remember, we just added a backdoor to our Kubernetes cluster!] .debug[[k8s/dashboard.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/dashboard.md)] --- ## Closing the backdoor - Seriously, don't leave that thing running! .lab[ - Remove what we just created: ```bash kubectl delete -f ~/container.training/k8s/dashboard-insecure.yaml ``` ] .debug[[k8s/dashboard.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/dashboard.md)] --- ## The risks - The steps that we just showed you are *for educational purposes only!* - If you do that on your production cluster, people [can and will abuse it](https://redlock.io/blog/cryptojacking-tesla) - For an in-depth discussion about securing the dashboard, <br/> check [this excellent post on Heptio's blog](https://blog.heptio.com/on-securing-the-kubernetes-dashboard-16b09b1b7aca) .debug[[k8s/dashboard.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/dashboard.md)] --- ## `dashboard-with-token.yaml` - This is a less risky way to deploy the dashboard - It's not completely secure, either: - we're using a self-signed certificate - this is subject to eavesdropping attacks - Using `kubectl port-forward` or `kubectl proxy` is even better .debug[[k8s/dashboard.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/dashboard.md)] --- ## What's in the manifest? - The dashboard itself (but exposed with a `NodePort`) - A ServiceAccount with `cluster-admin` privileges (named `kubernetes-dashboard:cluster-admin`) .lab[ - Create all the dashboard resources, with the following command: ```bash kubectl apply -f ~/container.training/k8s/dashboard-with-token.yaml ``` ] .debug[[k8s/dashboard.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/dashboard.md)] --- ## Obtaining the token - The manifest creates a ServiceAccount - Kubernetes will automatically generate a token for that ServiceAccount .lab[ - Display the token: ```bash kubectl --namespace=kubernetes-dashboard \ describe secret cluster-admin-token ``` ] The token should start with `eyJ...` (it's a JSON Web Token). Note that the secret name will actually be `cluster-admin-token-xxxxx`. <br/> (But `kubectl` prefix matches are great!) .debug[[k8s/dashboard.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/dashboard.md)] --- ## Connecting to the dashboard .lab[ - Check which port the dashboard is on: ```bash kubectl get svc --namespace=kubernetes-dashboard ``` ] You'll want the `3xxxx` port. .lab[ - Connect to http://oneofournodes:3xxxx/ <!-- ```open http://node1:3xxxx/``` --> ] The dashboard will then ask you which authentication you want to use. .debug[[k8s/dashboard.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/dashboard.md)] --- ## Dashboard authentication - Select "token" authentication - Copy paste the token (starting with `eyJ...`) obtained earlier - We're logged in! .debug[[k8s/dashboard.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/dashboard.md)] --- ## Other dashboards - [Kube Web View](https://codeberg.org/hjacobs/kube-web-view) - read-only dashboard - optimized for "troubleshooting and incident response" - see [vision and goals](https://kube-web-view.readthedocs.io/en/latest/vision.html#vision) for details - [Kube Ops View](https://codeberg.org/hjacobs/kube-ops-view) - "provides a common operational picture for multiple Kubernetes clusters" .debug[[k8s/dashboard.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/dashboard.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-security-implications-of-kubectl-apply class: title Security implications of `kubectl apply` .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-the-kubernetes-dashboard) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-3) | [Next part](#toc-ks) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Security implications of `kubectl apply` - When we do `kubectl apply -f <URL>`, we create arbitrary resources - Resources can be evil; imagine a `deployment` that ... -- - starts bitcoin miners on the whole cluster -- - hides in a non-default namespace -- - bind-mounts our nodes' filesystem -- - inserts SSH keys in the root account (on the node) -- - encrypts our data and ransoms it -- - ☠️☠️☠️ .debug[[k8s/dashboard.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/dashboard.md)] --- ## `kubectl apply` is the new `curl | sh` - `curl | sh` is convenient - It's safe if you use HTTPS URLs from trusted sources -- - `kubectl apply -f` is convenient - It's safe if you use HTTPS URLs from trusted sources - Example: the official setup instructions for most pod networks -- - It introduces new failure modes (for instance, if you try to apply YAML from a link that's no longer valid) ??? :EN:- The Kubernetes dashboard :FR:- Le *dashboard* Kubernetes .debug[[k8s/dashboard.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/dashboard.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-ks class: title k9s .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-security-implications-of-kubectl-apply) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-3) | [Next part](#toc-tilt) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # k9s - Somewhere in between CLI and GUI (or web UI), we can find the magic land of TUI - [Text-based user interfaces](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Text-based_user_interface) - often using libraries like [curses](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Curses_%28programming_library%29) and its successors - Some folks love them, some folks hate them, some are indifferent ... - But it's nice to have different options! - Let's see one particular TUI for Kubernetes: [k9s](https://k9scli.io/) .debug[[k8s/k9s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/k9s.md)] --- ## Installing k9s - If you are using a training cluster or the [shpod](https://github.com/jpetazzo/shpod) image, k9s is pre-installed - Otherwise, it can be installed easily: - with [various package managers](https://k9scli.io/topics/install/) - or by fetching a [binary release](https://github.com/derailed/k9s/releases) - We don't need to set up or configure anything (it will use the same configuration as `kubectl` and other well-behaved clients) - Just run `k9s` to fire it up! .debug[[k8s/k9s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/k9s.md)] --- ## What kind to we want to see? - Press `:` to change the type of resource to view - Then type, for instance, `ns` or `namespace` or `nam[TAB]`, then `[ENTER]` - Use the arrows to move down to e.g. `kube-system`, and press `[ENTER]` - Or, type `/kub` or `/sys` to filter the output, and press `[ENTER]` twice (once to exit the filter, once to enter the namespace) - We now see the pods in `kube-system`! .debug[[k8s/k9s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/k9s.md)] --- ## Interacting with pods - `l` to view logs - `d` to describe - `s` to get a shell (won't work if `sh` isn't available in the container image) - `e` to edit - `shift-f` to define port forwarding - `ctrl-k` to kill - `[ESC]` to get out or get back .debug[[k8s/k9s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/k9s.md)] --- ## Quick navigation between namespaces - On top of the screen, we should see shortcuts like this: ``` <0> all <1> kube-system <2> default ``` - Pressing the corresponding number switches to that namespace (or shows resources across all namespaces with `0`) - Locate a namespace with a copy of DockerCoins, and go there! .debug[[k8s/k9s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/k9s.md)] --- ## Interacting with Deployments - View Deployments (type `:` `deploy` `[ENTER]`) - Select e.g. `worker` - Scale it with `s` - View its aggregated logs with `l` .debug[[k8s/k9s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/k9s.md)] --- ## Exit - Exit at any time with `Ctrl-C` - k9s will "remember" where you were (and go back there next time you run it) .debug[[k8s/k9s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/k9s.md)] --- ## Pros - Very convenient to navigate through resources (hopping from a deployment, to its pod, to another namespace, etc.) - Very convenient to quickly view logs of e.g. init containers - Very convenient to get a (quasi) realtime view of resources (if we use `watch kubectl get` a lot, we will probably like k9s) .debug[[k8s/k9s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/k9s.md)] --- ## Cons - Doesn't promote automation / scripting (if you repeat the same things over and over, there is a scripting opportunity) - Not all features are available (e.g. executing arbitrary commands in containers) .debug[[k8s/k9s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/k9s.md)] --- ## Conclusion Try it out, and see if it makes you more productive! ??? :EN:- The k9s TUI :FR:- L'interface texte k9s .debug[[k8s/k9s.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/k9s.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-tilt class: title Tilt .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-ks) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-3) | [Next part](#toc-exercise--healthchecks) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Tilt - What does a development workflow look like? - make changes - test / see these changes - repeat! - What does it look like, with containers? 🤔 .debug[[k8s/tilt.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/tilt.md)] --- ## Basic Docker workflow - Preparation - write Dockerfiles - Iteration - edit code - `docker build` - `docker run` - test - `docker stop` Straightforward when we have a single container. .debug[[k8s/tilt.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/tilt.md)] --- ## Docker workflow with volumes - Preparation - write Dockerfiles - `docker build` + `docker run` - Iteration - edit code - test Note: only works with interpreted languages. <br/> (Compiled languages require extra work.) .debug[[k8s/tilt.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/tilt.md)] --- ## Docker workflow with Compose - Preparation - write Dockerfiles + Compose file - `docker-compose up` - Iteration - edit code - test - `docker-compose up` (as needed) Simplifies complex scenarios (multiple containers). <br/> Facilitates updating images. .debug[[k8s/tilt.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/tilt.md)] --- ## Basic Kubernetes workflow - Preparation - write Dockerfiles - write Kubernetes YAML - set up container registry - Iteration - edit code - build images - push images - update Kubernetes resources Seems simple enough, right? .debug[[k8s/tilt.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/tilt.md)] --- ## Basic Kubernetes workflow - Preparation - write Dockerfiles - write Kubernetes YAML - **set up container registry** - Iteration - edit code - build images - **push images** - update Kubernetes resources Ah, right ... .debug[[k8s/tilt.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/tilt.md)] --- ## We need a registry - Remember "build, ship, and run" - Registries are involved in the "ship" phase - With Docker, we were building and running on the same node - We didn't need a registry! - With Kubernetes, though ... .debug[[k8s/tilt.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/tilt.md)] --- ## Special case of single node clusters - If our Kubernetes has only one node ... - ... We can build directly on that node ... - ... We don't need to push images ... - ... We don't need to run a registry! - Examples: Docker Desktop, Minikube ... .debug[[k8s/tilt.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/tilt.md)] --- ## When we have more than one node - Which registry should we use? (Docker Hub, Quay, cloud-based, self-hosted ...) - Should we use a single registry, or one per cluster or environment? - Which tags and credentials should we use? (in particular when using a shared registry!) - How do we provision that registry and its users? - How do we adjust our Kubernetes YAML manifests? (e.g. to inject image names and tags) .debug[[k8s/tilt.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/tilt.md)] --- ## More questions - The whole cycle (build+push+update) is expensive - If we have many services, how do we update only the ones we need? - Can we take shortcuts? (e.g. synchronized files without going through a whole build+push+update cycle) .debug[[k8s/tilt.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/tilt.md)] --- ## Tilt - Tilt is a tool to address all these questions - There are other similar tools (e.g. Skaffold) - We arbitrarily decided to focus on that one .debug[[k8s/tilt.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/tilt.md)] --- ## Tilt in practice - The `dockercoins` directory in our repository has a `Tiltfile` - That Tiltfile includes definitions for the DockerCoins app, including: - building the images for the app - Kubernetes manifests to deploy the app - a self-hosted registry to host the app image - Let's try it out! .debug[[k8s/tilt.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/tilt.md)] --- ## Running Tilt locally *These instructions are valid only if you run Tilt on your local machine.* *If you are running Tilt on a remote machine or in a Pod, see next slide.* - Start Tilt: ```bash tilt up ``` - Then press "space" or connect to http://localhost:10350/ .debug[[k8s/tilt.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/tilt.md)] --- ## Running Tilt on a remote machine - If Tilt runs remotely, we can't access `http://localhost:10350` - We'll need to tell Tilt to listen to `0.0.0.0` (instead of just `localhost`) - If we run Tilt in a Pod, we need to expose port 10350 somehow (and Tilt needs to listen on `0.0.0.0`, too) .debug[[k8s/tilt.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/tilt.md)] --- ## Telling Tilt to listen in `0.0.0.0` - This can be done with the `--host` flag: ```bash tilt --host=0.0.0.0 ``` - Or by setting the `TILT_HOST` environment variable: ```bash export TILT_HOST=0.0.0.0 tilt up ``` .debug[[k8s/tilt.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/tilt.md)] --- ## Running Tilt in a Pod If you use `shpod`, you can use the following command: ```bash kubectl patch service shpod --namespace shpod -p " spec: ports: - name: tilt port: 10350 targetPort: 10350 nodePort: 30150 protocol: TCP " ``` Then connect to port 30150 on any of your nodes. If you use something else than `shpod`, adapt these instructions! .debug[[k8s/tilt.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/tilt.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Kubernetes contexts - Tilt is designed to run in dev environments - It will try to figure out if we're really in a dev environment: - if Tilt thinks that are on a local dev cluster, it will start - otherwise, it will give us a warning and it won't continue - In the latter case, we need to add one line to the Tiltfile (to tell Tilt "it's okay, you can run safely in this environment!") - If this happens, add the line to the Tiltfile (Tilt will tell you exactly what to add!) - We don't need to restart Tilt, it will detect the change immediately .debug[[k8s/tilt.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/tilt.md)] --- ## What's in our Tiltfile? - Kubernetes manifests for a local registry - Kubernetes manifests for DockerCoins - Instructions indicating how to build DockerCoins' images - A tiny bit of sugar (telling Tilt which registry to use) .debug[[k8s/tilt.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/tilt.md)] --- ## How does it work? - Tilt keeps track of dependencies between files and resources (a bit like a `make` that would run continuously) - It automatically alters some resources (for instance, it updates the images used in our Kubernetes manifests) - That's it! (And of course, it provides a great web UI, lots of libraries, etc.) .debug[[k8s/tilt.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/tilt.md)] --- ## What happens when we edit a file (1/2) - Let's change e.g. `worker/worker.py` - Thanks to this line, ```python docker_build('dockercoins/worker', 'worker') ``` ... Tilt watches the `worker` directory and uses it to build `dockercoins/worker` - Thanks to this line, ```python default_registry('localhost:30555') ``` ... Tilt actually renames `dockercoins/worker` to `localhost:30555/dockercoins_worker` - Tilt will tag the image with something like `tilt-xxxxxxxxxx` .debug[[k8s/tilt.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/tilt.md)] --- ## What happens when we edit a file (2/2) - Thanks to this line, ```python k8s_yaml('../k8s/dockercoins.yaml') ``` ... Tilt is aware of our Kubernetes resources - The `worker` Deployment uses `dockercoins/worker`, so it must be updated - `dockercoins/worker` becomes `localhost:30555/dockercoins_worker:tilt-xxx` - The `worker` Deployment gets updated on the Kubernetes cluster - All these operations (and their log output) are visible in the Tilt UI .debug[[k8s/tilt.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/tilt.md)] --- ## Configuration file format - The Tiltfile is written in [Starlark](https://github.com/bazelbuild/starlark) (essentially a subset of Python) - Tilt monitors the Tiltfile too (so it reloads it immediately when we change it) .debug[[k8s/tilt.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/tilt.md)] --- ## Tilt "killer features" - Dependency engine (build or run only what's necessary) - Ability to watch resources (execute actions immediately, without explicitly running a command) - Rich library of function and helpers (build container images, manipulate YAML manifests...) - Convenient UI (web; TUI also available) (provides immediate feedback and logs) - Extensibility! ??? :EN:- Development workflow with Tilt :FR:- Développer avec Tilt .debug[[k8s/tilt.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/tilt.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-exercise--healthchecks class: title Exercise — Healthchecks .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-tilt) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-3) | [Next part](#toc-exposing-http-services-with-ingress-resources) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Exercise — Healthchecks - We want to add healthchecks to the `rng` service in dockercoins - The `rng` service exhibits an interesting behavior under load: *its latency increases (which will cause probes to time out!)* - We want to see: - what happens when the readiness probe fails - what happens when the liveness probe fails - how to set "appropriate" probes and probe parameters .debug[[exercises/healthchecks-details.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/exercises/healthchecks-details.md)] --- ## Setup - First, deploy a new copy of dockercoins (for instance, in a brand new namespace) - Pro tip #1: ping (e.g. with `httping`) the `rng` service at all times - it should initially show a few milliseconds latency - that will increase when we scale up - it will also let us detect when the service goes "boom" - Pro tip #2: also keep an eye on the web UI .debug[[exercises/healthchecks-details.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/exercises/healthchecks-details.md)] --- ## Readiness - Add a readiness probe to `rng` - this requires editing the pod template in the Deployment manifest - use a simple HTTP check on the `/` route of the service - keep all other parameters (timeouts, thresholds...) at their default values - Check what happens when deploying an invalid image for `rng` (e.g. `alpine`) *(If the probe was set up correctly, the app will continue to work, because Kubernetes won't switch over the traffic to the `alpine` containers, because they don't pass the readiness probe.)* .debug[[exercises/healthchecks-details.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/exercises/healthchecks-details.md)] --- ## Readiness under load - Then roll back `rng` to the original image - Check what happens when we scale up the `worker` Deployment to 15+ workers (get the latency above 1 second) *(We should now observe intermittent unavailability of the service, i.e. every 30 seconds it will be unreachable for a bit, then come back, then go away again, etc.)* .debug[[exercises/healthchecks-details.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/exercises/healthchecks-details.md)] --- ## Liveness - Now replace the readiness probe with a liveness probe - What happens now? *(At first the behavior looks the same as with the readiness probe: service becomes unreachable, then reachable again, etc.; but there is a significant difference behind the scenes. What is it?)* .debug[[exercises/healthchecks-details.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/exercises/healthchecks-details.md)] --- ## Readiness and liveness - Bonus questions! - What happens if we enable both probes at the same time? - What strategies can we use so that both probes are useful? .debug[[exercises/healthchecks-details.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/exercises/healthchecks-details.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-exposing-http-services-with-ingress-resources class: title Exposing HTTP services with Ingress resources .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-exercise--healthchecks) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-4) | [Next part](#toc-volumes) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Exposing HTTP services with Ingress resources - Service = layer 4 (TCP, UDP, SCTP) - works with every TCP/UDP/SCTP protocol - doesn't "see" or interpret HTTP - Ingress = layer 7 (HTTP) - only for HTTP - can route requests depending on URI or host header - can handle TLS .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- ## Why should we use Ingress resources? A few use-cases: - URI routing (e.g. for single page apps) `/api` → service `api:5000` everything else → service `static:80` - Cost optimization (because individual `LoadBalancer` services typically cost money) - Automatic handling of TLS certificates .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- ## `LoadBalancer` vs `Ingress` - Service with `type: LoadBalancer` - requires a particular controller (e.g. CCM, MetalLB) - if TLS is desired, it has to be implemented by the app - works for any TCP protocol (not just HTTP) - doesn't interpret the HTTP protocol (no fancy routing) - costs a bit of money for each service - Ingress - requires an ingress controller - can implement TLS transparently for the app - only supports HTTP - can do content-based routing (e.g. per URI) - lower cost per service <br/>(exact pricing depends on provider's model) .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- ## Ingress resources - Kubernetes API resource (`kubectl get ingress`/`ingresses`/`ing`) - Designed to expose HTTP services - Requires an *ingress controller* (otherwise, resources can be created, but nothing happens) - Some ingress controllers are based on existing load balancers (HAProxy, NGINX...) - Some are standalone, and sometimes designed for Kubernetes (Contour, Traefik...) - Note: there is no "default" or "official" ingress controller! .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- ## Ingress standard features - Load balancing - SSL termination - Name-based virtual hosting - URI routing (e.g. `/api`→`api-service`, `/static`→`assets-service`) .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- ## Ingress extended features (Not always supported; supported through annotations, CRDs, etc.) - Routing with other headers or cookies - A/B testing - Canary deployment - etc. .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- ## Principle of operation - Step 1: deploy an *ingress controller* (one-time setup) - Step 2: create *Ingress resources* - maps a domain and/or path to a Kubernetes Service - the controller watches ingress resources and sets up a LB - Step 3: set up DNS - associate DNS entries with the load balancer address .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Special cases - GKE has "[GKE Ingress]", a custom ingress controller (enabled by default) - EKS has "AWS ALB Ingress Controller" as well (not enabled by default, requires extra setup) - They leverage cloud-specific HTTP load balancers (GCP HTTP LB, AWS ALB) - They typically a cost *per ingress resource* [GKE Ingress]: https://cloud.google.com/kubernetes-engine/docs/concepts/ingress .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Single or multiple LoadBalancer - Most ingress controllers will create a LoadBalancer Service (and will receive all HTTP/HTTPS traffic through it) - We need to point our DNS entries to the IP address of that LB - Some rare ingress controllers will allocate one LB per ingress resource (example: the GKE Ingress and ALB Ingress mentioned previously) - This leads to increased costs - Note that it's possible to have multiple "rules" per ingress resource (this will reduce costs but may be less convenient to manage) .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- ## Ingress in action - We will deploy the Traefik ingress controller - this is an arbitrary choice - maybe motivated by the fact that Traefik releases are named after cheeses - For DNS, we will use [nip.io](http://nip.io/) - `*.1.2.3.4.nip.io` resolves to `1.2.3.4` - We will create ingress resources for various HTTP services .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- ## Accepting connections on port 80 (and 443) - Web site users don't want to specify port numbers (e.g. "connect to https://blahblah.whatever:31550") - Our ingress controller needs to actually be exposed on port 80 (and 443 if we want to handle HTTPS) - Let's see how we can achieve that! .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- ## Various ways to expose something on port 80 - Service with `type: LoadBalancer` *costs a little bit of money; not always available* - Service with one (or multiple) `ExternalIP` *requires public nodes; limited by number of nodes* - Service with `hostPort` or `hostNetwork` *same limitations as `ExternalIP`; even harder to manage* .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- ## Deploying pods listening on port 80 - We are going to run Traefik in Pods with `hostNetwork: true` (so that our load balancer can use the "real" port 80 of our nodes) - Traefik Pods will be created by a DaemonSet (so that we get one instance of Traefik on every node of the cluster) - This means that we will be able to connect to any node of the cluster on port 80 .warning[This is not typical of a production setup!] .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- ## Doing it in production - When running "on cloud", the easiest option is a `LoadBalancer` service - When running "on prem", it depends: - [MetalLB] is a good option if a pool of public IP addresses is available - otherwise, using `externalIPs` on a few nodes (2-3 for redundancy) - Many variations/optimizations are possible depending on our exact scenario! [MetalLB]: https://metallb.org/ .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Without `hostNetwork` - Normally, each pod gets its own *network namespace* (sometimes called sandbox or network sandbox) - An IP address is assigned to the pod - This IP address is routed/connected to the cluster network - All containers of that pod are sharing that network namespace (and therefore using the same IP address) .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- class: extra-details ## With `hostNetwork: true` - No network namespace gets created - The pod is using the network namespace of the host - It "sees" (and can use) the interfaces (and IP addresses) of the host - The pod can receive outside traffic directly, on any port - Downside: with most network plugins, network policies won't work for that pod - most network policies work at the IP address level - filtering that pod = filtering traffic from the node .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- ## Running Traefik - The [Traefik documentation][traefikdoc] recommends to use a Helm chart - For simplicity, we're going to use a custom YAML manifest - Our manifest will: - use a Daemon Set so that each node can accept connections - enable `hostNetwork` - add a *toleration* so that Traefik also runs on all nodes - We could do the same with the official [Helm chart][traefikchart] [traefikdoc]: https://doc.traefik.io/traefik/getting-started/install-traefik/#use-the-helm-chart [traefikchart]: https://artifacthub.io/packages/helm/traefik/traefik .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Taints and tolerations - A *taint* is an attribute added to a node - It prevents pods from running on the node - ... Unless they have a matching *toleration* - When deploying with `kubeadm`: - a taint is placed on the node dedicated to the control plane - the pods running the control plane have a matching toleration .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Checking taints on our nodes .lab[ - Check our nodes specs: ```bash kubectl get node node1 -o json | jq .spec kubectl get node node2 -o json | jq .spec ``` ] We should see a result only for `node1` (the one with the control plane): ```json "taints": [ { "effect": "NoSchedule", "key": "node-role.kubernetes.io/master" } ] ``` .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Understanding a taint - The `key` can be interpreted as: - a reservation for a special set of pods <br/> (here, this means "this node is reserved for the control plane") - an error condition on the node <br/> (for instance: "disk full," do not start new pods here!) - The `effect` can be: - `NoSchedule` (don't run new pods here) - `PreferNoSchedule` (try not to run new pods here) - `NoExecute` (don't run new pods and evict running pods) .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Checking tolerations on the control plane .lab[ - Check tolerations for CoreDNS: ```bash kubectl -n kube-system get deployments coredns -o json | jq .spec.template.spec.tolerations ``` ] The result should include: ```json { "effect": "NoSchedule", "key": "node-role.kubernetes.io/master" } ``` It means: "bypass the exact taint that we saw earlier on `node1`." .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Special tolerations .lab[ - Check tolerations on `kube-proxy`: ```bash kubectl -n kube-system get ds kube-proxy -o json | jq .spec.template.spec.tolerations ``` ] The result should include: ```json { "operator": "Exists" } ``` This one is a special case that means "ignore all taints and run anyway." .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- ## Running Traefik on our cluster - We provide a YAML file (`k8s/traefik.yaml`) which is essentially the sum of: - [Traefik's Daemon Set resources](https://github.com/containous/traefik/blob/v1.7/examples/k8s/traefik-ds.yaml) (patched with `hostNetwork` and tolerations) - [Traefik's RBAC rules](https://github.com/containous/traefik/blob/v1.7/examples/k8s/traefik-rbac.yaml) allowing it to watch necessary API objects .lab[ - Apply the YAML: ```bash kubectl apply -f ~/container.training/k8s/traefik.yaml ``` ] .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- ## Checking that Traefik runs correctly - If Traefik started correctly, we now have a web server listening on each node .lab[ - Check that Traefik is serving 80/tcp: ```bash curl localhost ``` ] We should get a `404 page not found` error. This is normal: we haven't provided any ingress rule yet. .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- ## Setting up DNS - To make our lives easier, we will use [nip.io](http://nip.io) - Check out `http://red.A.B.C.D.nip.io` (replacing A.B.C.D with the IP address of `node1`) - We should get the same `404 page not found` error (meaning that our DNS is "set up properly", so to speak!) .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- ## Traefik web UI - Traefik provides a web dashboard - With the current install method, it's listening on port 8080 .lab[ - Go to `http://node1:8080` (replacing `node1` with its IP address) <!-- ```open http://node1:8080``` --> ] .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- ## Setting up host-based routing ingress rules - We are going to use the `jpetazzo/color` image - This image contains a simple static HTTP server on port 80 - We will run 3 deployments (`red`, `green`, `blue`) - We will create 3 services (one for each deployment) - Then we will create 3 ingress rules (one for each service) - We will route `<color>.A.B.C.D.nip.io` to the corresponding deployment .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- ## Running colorful web servers .lab[ - Run all three deployments: ```bash kubectl create deployment red --image=jpetazzo/color kubectl create deployment green --image=jpetazzo/color kubectl create deployment blue --image=jpetazzo/color ``` - Create a service for each of them: ```bash kubectl expose deployment red --port=80 kubectl expose deployment green --port=80 kubectl expose deployment blue --port=80 ``` ] .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- ## Creating ingress resources - Since Kubernetes 1.19, we can use `kubectl create ingress` ```bash kubectl create ingress red \ --rule=red.`A.B.C.D`.nip.io/*=red:80 ``` - We can specify multiple rules per resource ```bash kubectl create ingress rgb \ --rule=red.`A.B.C.D`.nip.io/*=red:80 \ --rule=green.`A.B.C.D`.nip.io/*=green:80 \ --rule=blue.`A.B.C.D`.nip.io/*=blue:80 ``` .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- ## Pay attention to the `*`! - The `*` is important: ``` --rule=red.A.B.C.D.nip.io/`*`=red:80 ``` - It means "all URIs below that path" - Without the `*`, it means "only that exact path" (if we omit it, requests for e.g. `red.A.B.C.D.nip.io/hello` will 404) .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- ## Before Kubernetes 1.19 - Before Kubernetes 1.19: - `kubectl create ingress` wasn't available - `apiVersion: networking.k8s.io/v1` wasn't supported - It was necessary to use YAML, and `apiVersion: networking.k8s.io/v1beta1` (see example on next slide) .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- ## YAML for old ingress resources Here is a minimal host-based ingress resource: ```yaml apiVersion: networking.k8s.io/v1beta1 kind: Ingress metadata: name: red spec: rules: - host: red.`A.B.C.D`.nip.io http: paths: - path: / backend: serviceName: red servicePort: 80 ``` .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- ## YAML for new ingress resources - Starting with Kubernetes 1.19, `networking.k8s.io/v1` is available - And we can use `kubectl create ingress` 🎉 - We can see "modern" YAML with `-o yaml --dry-run=client`: ```bash kubectl create ingress red -o yaml --dry-run=client \ --rule=red.`A.B.C.D`.nip.io/*=red:80 ``` .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- ## Creating ingress resources - Create the ingress resources with `kubectl create ingress` (or use the YAML manifests if using Kubernetes 1.18 or older) - Make sure to update the hostnames! - Check that you can connect to the exposed web apps .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Using multiple ingress controllers - You can have multiple ingress controllers active simultaneously (e.g. Traefik and NGINX) - You can even have multiple instances of the same controller (e.g. one for internal, another for external traffic) - To indicate which ingress controller should be used by a given Ingress resouce: - before Kubernetes 1.18, use the `kubernetes.io/ingress.class` annotation - since Kubernetes 1.18, use the `ingressClassName` field <br/> (which should refer to an existing `IngressClass` resource) .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- ## Ingress shortcomings - A lot of things have been left out of the Ingress v1 spec (routing requests according to weight, cookies, across namespaces...) - Example: stripping path prefixes - NGINX: [nginx.ingress.kubernetes.io/rewrite-target: /](https://github.com/kubernetes/ingress-nginx/blob/main/docs/examples/rewrite/README.md) - Traefik v1: [traefik.ingress.kubernetes.io/rule-type: PathPrefixStrip](https://doc.traefik.io/traefik/migration/v1-to-v2/#strip-and-rewrite-path-prefixes) - Traefik v2: [requires a CRD](https://doc.traefik.io/traefik/migration/v1-to-v2/#strip-and-rewrite-path-prefixes) .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- ## Ingress in the future - The [Gateway API SIG](https://gateway-api.sigs.k8s.io/) might be the future of Ingress - It proposes new resources: GatewayClass, Gateway, HTTPRoute, TCPRoute... - It is still in alpha stage ??? :EN:- The Ingress resource :FR:- La ressource *ingress* .debug[[k8s/ingress.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/ingress.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-volumes class: title Volumes .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-exposing-http-services-with-ingress-resources) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-4) | [Next part](#toc-managing-configuration) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Volumes - Volumes are special directories that are mounted in containers - Volumes can have many different purposes: - share files and directories between containers running on the same machine - share files and directories between containers and their host - centralize configuration information in Kubernetes and expose it to containers - manage credentials and secrets and expose them securely to containers - store persistent data for stateful services - access storage systems (like Ceph, EBS, NFS, Portworx, and many others) .debug[[k8s/volumes.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/volumes.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Kubernetes volumes vs. Docker volumes - Kubernetes and Docker volumes are very similar (the [Kubernetes documentation](https://kubernetes.io/docs/concepts/storage/volumes/) says otherwise ... <br/> but it refers to Docker 1.7, which was released in 2015!) - Docker volumes allow us to share data between containers running on the same host - Kubernetes volumes allow us to share data between containers in the same pod - Both Docker and Kubernetes volumes enable access to storage systems - Kubernetes volumes are also used to expose configuration and secrets - Docker has specific concepts for configuration and secrets <br/> (but under the hood, the technical implementation is similar) - If you're not familiar with Docker volumes, you can safely ignore this slide! .debug[[k8s/volumes.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/volumes.md)] --- ## Volumes ≠ Persistent Volumes - Volumes and Persistent Volumes are related, but very different! - *Volumes*: - appear in Pod specifications (we'll see that in a few slides) - do not exist as API resources (**cannot** do `kubectl get volumes`) - *Persistent Volumes*: - are API resources (**can** do `kubectl get persistentvolumes`) - correspond to concrete volumes (e.g. on a SAN, EBS, etc.) - cannot be associated with a Pod directly; but through a Persistent Volume Claim - won't be discussed further in this section .debug[[k8s/volumes.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/volumes.md)] --- ## Adding a volume to a Pod - We will start with the simplest Pod manifest we can find - We will add a volume to that Pod manifest - We will mount that volume in a container in the Pod - By default, this volume will be an `emptyDir` (an empty directory) - It will "shadow" the directory where it's mounted .debug[[k8s/volumes.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/volumes.md)] --- ## Our basic Pod ```yaml apiVersion: v1 kind: Pod metadata: name: nginx-without-volume spec: containers: - name: nginx image: nginx ``` This is a MVP! (Minimum Viable Pod😉) It runs a single NGINX container. .debug[[k8s/volumes.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/volumes.md)] --- ## Trying the basic pod .lab[ - Create the Pod: ```bash kubectl create -f ~/container.training/k8s/nginx-1-without-volume.yaml ``` <!-- ```bash kubectl wait pod/nginx-without-volume --for condition=ready ``` --> - Get its IP address: ```bash IPADDR=$(kubectl get pod nginx-without-volume -o jsonpath={.status.podIP}) ``` - Send a request with curl: ```bash curl $IPADDR ``` ] (We should see the "Welcome to NGINX" page.) .debug[[k8s/volumes.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/volumes.md)] --- ## Adding a volume - We need to add the volume in two places: - at the Pod level (to declare the volume) - at the container level (to mount the volume) - We will declare a volume named `www` - No type is specified, so it will default to `emptyDir` (as the name implies, it will be initialized as an empty directory at pod creation) - In that pod, there is also a container named `nginx` - That container mounts the volume `www` to path `/usr/share/nginx/html/` .debug[[k8s/volumes.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/volumes.md)] --- ## The Pod with a volume ```yaml apiVersion: v1 kind: Pod metadata: name: nginx-with-volume spec: volumes: - name: www containers: - name: nginx image: nginx volumeMounts: - name: www mountPath: /usr/share/nginx/html/ ``` .debug[[k8s/volumes.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/volumes.md)] --- ## Trying the Pod with a volume .lab[ - Create the Pod: ```bash kubectl create -f ~/container.training/k8s/nginx-2-with-volume.yaml ``` <!-- ```bash kubectl wait pod/nginx-with-volume --for condition=ready ``` --> - Get its IP address: ```bash IPADDR=$(kubectl get pod nginx-with-volume -o jsonpath={.status.podIP}) ``` - Send a request with curl: ```bash curl $IPADDR ``` ] (We should now see a "403 Forbidden" error page.) .debug[[k8s/volumes.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/volumes.md)] --- ## Populating the volume with another container - Let's add another container to the Pod - Let's mount the volume in *both* containers - That container will populate the volume with static files - NGINX will then serve these static files - To populate the volume, we will clone the Spoon-Knife repository - this repository is https://github.com/octocat/Spoon-Knife - it's very popular (more than 100K stars!) .debug[[k8s/volumes.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/volumes.md)] --- ## Sharing a volume between two containers .small[ ```yaml apiVersion: v1 kind: Pod metadata: name: nginx-with-git spec: volumes: - name: www containers: - name: nginx image: nginx volumeMounts: - name: www mountPath: /usr/share/nginx/html/ - name: git image: alpine command: [ "sh", "-c", "apk add git && git clone https://github.com/octocat/Spoon-Knife /www" ] volumeMounts: - name: www mountPath: /www/ restartPolicy: OnFailure ``` ] .debug[[k8s/volumes.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/volumes.md)] --- ## Sharing a volume, explained - We added another container to the pod - That container mounts the `www` volume on a different path (`/www`) - It uses the `alpine` image - When started, it installs `git` and clones the `octocat/Spoon-Knife` repository (that repository contains a tiny HTML website) - As a result, NGINX now serves this website .debug[[k8s/volumes.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/volumes.md)] --- ## Trying the shared volume - This one will be time-sensitive! - We need to catch the Pod IP address *as soon as it's created* - Then send a request to it *as fast as possible* .lab[ - Watch the pods (so that we can catch the Pod IP address) ```bash kubectl get pods -o wide --watch ``` <!-- ```wait NAME``` ```tmux split-pane -v``` --> ] .debug[[k8s/volumes.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/volumes.md)] --- ## Shared volume in action .lab[ - Create the pod: ```bash kubectl create -f ~/container.training/k8s/nginx-3-with-git.yaml ``` <!-- ```bash kubectl wait pod/nginx-with-git --for condition=initialized``` ```bash IP=$(kubectl get pod nginx-with-git -o jsonpath={.status.podIP})``` --> - As soon as we see its IP address, access it: ```bash curl `$IP` ``` <!-- ```bash /bin/sleep 5``` --> - A few seconds later, the state of the pod will change; access it again: ```bash curl `$IP` ``` ] The first time, we should see "403 Forbidden". The second time, we should see the HTML file from the Spoon-Knife repository. .debug[[k8s/volumes.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/volumes.md)] --- ## Explanations - Both containers are started at the same time - NGINX starts very quickly (it can serve requests immediately) - But at this point, the volume is empty (NGINX serves "403 Forbidden") - The other containers installs git and clones the repository (this takes a bit longer) - When the other container is done, the volume holds the repository (NGINX serves the HTML file) .debug[[k8s/volumes.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/volumes.md)] --- ## The devil is in the details - The default `restartPolicy` is `Always` - This would cause our `git` container to run again ... and again ... and again (with an exponential back-off delay, as explained [in the documentation](https://kubernetes.io/docs/concepts/workloads/pods/pod-lifecycle/#restart-policy)) - That's why we specified `restartPolicy: OnFailure` .debug[[k8s/volumes.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/volumes.md)] --- ## Inconsistencies - There is a short period of time during which the website is not available (because the `git` container hasn't done its job yet) - With a bigger website, we could get inconsistent results (where only a part of the content is ready) - In real applications, this could cause incorrect results - How can we avoid that? .debug[[k8s/volumes.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/volumes.md)] --- ## Init Containers - We can define containers that should execute *before* the main ones - They will be executed in order (instead of in parallel) - They must all succeed before the main containers are started - This is *exactly* what we need here! - Let's see one in action .footnote[See [Init Containers](https://kubernetes.io/docs/concepts/workloads/pods/init-containers/) documentation for all the details.] .debug[[k8s/volumes.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/volumes.md)] --- ## Defining Init Containers .small[ ```yaml apiVersion: v1 kind: Pod metadata: name: nginx-with-init spec: volumes: - name: www containers: - name: nginx image: nginx volumeMounts: - name: www mountPath: /usr/share/nginx/html/ initContainers: - name: git image: alpine command: [ "sh", "-c", "apk add git && git clone https://github.com/octocat/Spoon-Knife /www" ] volumeMounts: - name: www mountPath: /www/ ``` ] .debug[[k8s/volumes.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/volumes.md)] --- ## Trying the init container .lab[ - Create the pod: ```bash kubectl create -f ~/container.training/k8s/nginx-4-with-init.yaml ``` - Try to send HTTP requests as soon as the pod comes up <!-- ```key ^D``` ```key ^C``` --> ] - This time, instead of "403 Forbidden" we get a "connection refused" - NGINX doesn't start until the git container has done its job - We never get inconsistent results (a "half-ready" container) .debug[[k8s/volumes.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/volumes.md)] --- ## Other uses of init containers - Load content - Generate configuration (or certificates) - Database migrations - Waiting for other services to be up (to avoid flurry of connection errors in main container) - etc. .debug[[k8s/volumes.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/volumes.md)] --- ## Volume lifecycle - The lifecycle of a volume is linked to the pod's lifecycle - This means that a volume is created when the pod is created - This is mostly relevant for `emptyDir` volumes (other volumes, like remote storage, are not "created" but rather "attached" ) - A volume survives across container restarts - A volume is destroyed (or, for remote storage, detached) when the pod is destroyed ??? :EN:- Sharing data between containers with volumes :EN:- When and how to use Init Containers :FR:- Partager des données grâce aux volumes :FR:- Quand et comment utiliser un *Init Container* .debug[[k8s/volumes.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/volumes.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-managing-configuration class: title Managing configuration .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-volumes) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-4) | [Next part](#toc-managing-secrets) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Managing configuration - Some applications need to be configured (obviously!) - There are many ways for our code to pick up configuration: - command-line arguments - environment variables - configuration files - configuration servers (getting configuration from a database, an API...) - ... and more (because programmers can be very creative!) - How can we do these things with containers and Kubernetes? .debug[[k8s/configuration.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/configuration.md)] --- ## Passing configuration to containers - There are many ways to pass configuration to code running in a container: - baking it into a custom image - command-line arguments - environment variables - injecting configuration files - exposing it over the Kubernetes API - configuration servers - Let's review these different strategies! .debug[[k8s/configuration.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/configuration.md)] --- ## Baking custom images - Put the configuration in the image (it can be in a configuration file, but also `ENV` or `CMD` actions) - It's easy! It's simple! - Unfortunately, it also has downsides: - multiplication of images - different images for dev, staging, prod ... - minor reconfigurations require a whole build/push/pull cycle - Avoid doing it unless you don't have the time to figure out other options .debug[[k8s/configuration.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/configuration.md)] --- ## Command-line arguments - Indicate what should run in the container - Pass `command` and/or `args` in the container options in a Pod's template - Both `command` and `args` are arrays - Example ([source](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/blob/main/k8s/consul-1.yaml#L70)): ```yaml args: - "agent" - "-bootstrap-expect=3" - "-retry-join=provider=k8s label_selector=\"app=consul\" namespace=\"$(NS)\"" - "-client=0.0.0.0" - "-data-dir=/consul/data" - "-server" - "-ui" ``` .debug[[k8s/configuration.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/configuration.md)] --- ## `args` or `command`? - Use `command` to override the `ENTRYPOINT` defined in the image - Use `args` to keep the `ENTRYPOINT` defined in the image (the parameters specified in `args` are added to the `ENTRYPOINT`) - In doubt, use `command` - It is also possible to use *both* `command` and `args` (they will be strung together, just like `ENTRYPOINT` and `CMD`) - See the [docs](https://kubernetes.io/docs/tasks/inject-data-application/define-command-argument-container/#notes) to see how they interact together .debug[[k8s/configuration.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/configuration.md)] --- ## Command-line arguments, pros & cons - Works great when options are passed directly to the running program (otherwise, a wrapper script can work around the issue) - Works great when there aren't too many parameters (to avoid a 20-lines `args` array) - Requires documentation and/or understanding of the underlying program ("which parameters and flags do I need, again?") - Well-suited for mandatory parameters (without default values) - Not ideal when we need to pass a real configuration file anyway .debug[[k8s/configuration.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/configuration.md)] --- ## Environment variables - Pass options through the `env` map in the container specification - Example: ```yaml env: - name: ADMIN_PORT value: "8080" - name: ADMIN_AUTH value: Basic - name: ADMIN_CRED value: "admin:0pensesame!" ``` .warning[`value` must be a string! Make sure that numbers and fancy strings are quoted.] 🤔 Why this weird `{name: xxx, value: yyy}` scheme? It will be revealed soon! .debug[[k8s/configuration.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/configuration.md)] --- ## The downward API - In the previous example, environment variables have fixed values - We can also use a mechanism called the *downward API* - The downward API allows exposing pod or container information - either through special files (we won't show that for now) - or through environment variables - The value of these environment variables is computed when the container is started - Remember: environment variables won't (can't) change after container start - Let's see a few concrete examples! .debug[[k8s/configuration.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/configuration.md)] --- ## Exposing the pod's namespace ```yaml - name: MY_POD_NAMESPACE valueFrom: fieldRef: fieldPath: metadata.namespace ``` - Useful to generate FQDN of services (in some contexts, a short name is not enough) - For instance, the two commands should be equivalent: ``` curl api-backend curl api-backend.$MY_POD_NAMESPACE.svc.cluster.local ``` .debug[[k8s/configuration.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/configuration.md)] --- ## Exposing the pod's IP address ```yaml - name: MY_POD_IP valueFrom: fieldRef: fieldPath: status.podIP ``` - Useful if we need to know our IP address (we could also read it from `eth0`, but this is more solid) .debug[[k8s/configuration.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/configuration.md)] --- ## Exposing the container's resource limits ```yaml - name: MY_MEM_LIMIT valueFrom: resourceFieldRef: containerName: test-container resource: limits.memory ``` - Useful for runtimes where memory is garbage collected - Example: the JVM (the memory available to the JVM should be set with the `-Xmx ` flag) - Best practice: set a memory limit, and pass it to the runtime - Note: recent versions of the JVM can do this automatically (see [JDK-8146115](https://bugs.java.com/bugdatabase/view_bug.do?bug_id=JDK-8146115)) and [this blog post](https://very-serio.us/2017/12/05/running-jvms-in-kubernetes/) for detailed examples) .debug[[k8s/configuration.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/configuration.md)] --- ## More about the downward API - [This documentation page](https://kubernetes.io/docs/tasks/inject-data-application/environment-variable-expose-pod-information/) tells more about these environment variables - And [this one](https://kubernetes.io/docs/tasks/inject-data-application/downward-api-volume-expose-pod-information/) explains the other way to use the downward API (through files that get created in the container filesystem) - That second link also includes a list of all the fields that can be used with the downward API .debug[[k8s/configuration.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/configuration.md)] --- ## Environment variables, pros and cons - Works great when the running program expects these variables - Works great for optional parameters with reasonable defaults (since the container image can provide these defaults) - Sort of auto-documented (we can see which environment variables are defined in the image, and their values) - Can be (ab)used with longer values ... - ... You *can* put an entire Tomcat configuration file in an environment ... - ... But *should* you? (Do it if you really need to, we're not judging! But we'll see better ways.) .debug[[k8s/configuration.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/configuration.md)] --- ## Injecting configuration files - Sometimes, there is no way around it: we need to inject a full config file - Kubernetes provides a mechanism for that purpose: `configmaps` - A configmap is a Kubernetes resource that exists in a namespace - Conceptually, it's a key/value map (values are arbitrary strings) - We can think about them in (at least) two different ways: - as holding entire configuration file(s) - as holding individual configuration parameters *Note: to hold sensitive information, we can use "Secrets", which are another type of resource behaving very much like configmaps. We'll cover them just after!* .debug[[k8s/configuration.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/configuration.md)] --- ## Configmaps storing entire files - In this case, each key/value pair corresponds to a configuration file - Key = name of the file - Value = content of the file - There can be one key/value pair, or as many as necessary (for complex apps with multiple configuration files) - Examples: ``` # Create a configmap with a single key, "app.conf" kubectl create configmap my-app-config --from-file=app.conf # Create a configmap with a single key, "app.conf" but another file kubectl create configmap my-app-config --from-file=app.conf=app-prod.conf # Create a configmap with multiple keys (one per file in the config.d directory) kubectl create configmap my-app-config --from-file=config.d/ ``` .debug[[k8s/configuration.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/configuration.md)] --- ## Configmaps storing individual parameters - In this case, each key/value pair corresponds to a parameter - Key = name of the parameter - Value = value of the parameter - Examples: ``` # Create a configmap with two keys kubectl create cm my-app-config \ --from-literal=foreground=red \ --from-literal=background=blue # Create a configmap from a file containing key=val pairs kubectl create cm my-app-config \ --from-env-file=app.conf ``` .debug[[k8s/configuration.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/configuration.md)] --- ## Exposing configmaps to containers - Configmaps can be exposed as plain files in the filesystem of a container - this is achieved by declaring a volume and mounting it in the container - this is particularly effective for configmaps containing whole files - Configmaps can be exposed as environment variables in the container - this is achieved with the downward API - this is particularly effective for configmaps containing individual parameters - Let's see how to do both! .debug[[k8s/configuration.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/configuration.md)] --- ## Example: HAProxy configuration - We are going to deploy HAProxy, a popular load balancer - It expects to find its configuration in a specific place: `/usr/local/etc/haproxy/haproxy.cfg` - We will create a ConfigMap holding the configuration file - Then we will mount that ConfigMap in a Pod running HAProxy .debug[[k8s/configuration.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/configuration.md)] --- ## Blue/green load balancing - In this example, we will deploy two versions of our app: - the "blue" version in the `blue` namespace - the "green" version in the `green` namespace - In both namespaces, we will have a Deployment and a Service (both named `color`) - We want to load balance traffic between both namespaces (we can't do that with a simple service selector: these don't cross namespaces) .debug[[k8s/configuration.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/configuration.md)] --- ## Deploying the app - We're going to use the image `jpetazzo/color` (it is a simple "HTTP echo" server showing which pod served the request) - We can create each Namespace, Deployment, and Service by hand, or... .lab[ - We can deploy the app with a YAML manifest: ```bash kubectl apply -f ~/container.training/k8s/rainbow.yaml ``` ] .debug[[k8s/configuration.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/configuration.md)] --- ## Testing the app - Reminder: Service `x` in Namespace `y` is available through: `x.y`, `x.y.svc`, `x.y.svc.cluster.local` - Since the `cluster.local` suffix can change, we'll use `x.y.svc` .lab[ - Check that the app is up and running: ```bash kubectl run --rm -it --restart=Never --image=nixery.dev/curl my-test-pod \ curl color.blue.svc ``` ] .debug[[k8s/configuration.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/configuration.md)] --- ## Creating the HAProxy configuration Here is the file that we will use, [k8s/haproxy.cfg](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/master/k8s/haproxy.cfg): ``` global daemon defaults mode tcp timeout connect 5s timeout client 50s timeout server 50s listen very-basic-load-balancer bind *:80 server blue color.blue.svc:80 server green color.green.svc:80 # Note: the services above must exist, # otherwise HAproxy won't start. ``` .debug[[k8s/configuration.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/configuration.md)] --- ## Creating the ConfigMap .lab[ - Create a ConfigMap named `haproxy` and holding the configuration file: ```bash kubectl create configmap haproxy --from-file=~/container.training/k8s/haproxy.cfg ``` - Check what our configmap looks like: ```bash kubectl get configmap haproxy -o yaml ``` ] .debug[[k8s/configuration.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/configuration.md)] --- ## Using the ConfigMap Here is [k8s/haproxy.yaml](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/master/k8s/haproxy.yaml), a Pod manifest using that ConfigMap: ```yaml apiVersion: v1 kind: Pod metadata: name: haproxy spec: volumes: - name: config configMap: name: haproxy containers: - name: haproxy image: haproxy:1 volumeMounts: - name: config mountPath: /usr/local/etc/haproxy/ ``` .debug[[k8s/configuration.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/configuration.md)] --- ## Creating the Pod .lab[ - Create the HAProxy Pod: ```bash kubectl apply -f ~/container.training/k8s/haproxy.yaml ``` <!-- ```hide kubectl wait pod haproxy --for condition=ready``` --> - Check the IP address allocated to the pod: ```bash kubectl get pod haproxy -o wide IP=$(kubectl get pod haproxy -o json | jq -r .status.podIP) ``` ] .debug[[k8s/configuration.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/configuration.md)] --- ## Testing our load balancer - If everything went well, when we should see a perfect round robin (one request to `blue`, one request to `green`, one request to `blue`, etc.) .lab[ - Send a few requests: ```bash for i in $(seq 10); do curl $IP done ``` ] .debug[[k8s/configuration.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/configuration.md)] --- ## Exposing configmaps with the downward API - We are going to run a Docker registry on a custom port - By default, the registry listens on port 5000 - This can be changed by setting environment variable `REGISTRY_HTTP_ADDR` - We are going to store the port number in a configmap - Then we will expose that configmap as a container environment variable .debug[[k8s/configuration.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/configuration.md)] --- ## Creating the configmap .lab[ - Our configmap will have a single key, `http.addr`: ```bash kubectl create configmap registry --from-literal=http.addr=0.0.0.0:80 ``` - Check our configmap: ```bash kubectl get configmap registry -o yaml ``` ] .debug[[k8s/configuration.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/configuration.md)] --- ## Using the configmap We are going to use the following pod definition: ```yaml apiVersion: v1 kind: Pod metadata: name: registry spec: containers: - name: registry image: registry env: - name: REGISTRY_HTTP_ADDR valueFrom: configMapKeyRef: name: registry key: http.addr ``` .debug[[k8s/configuration.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/configuration.md)] --- ## Using the configmap - The resource definition from the previous slide is in [k8s/registry.yaml](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/master/k8s/registry.yaml) .lab[ - Create the registry pod: ```bash kubectl apply -f ~/container.training/k8s/registry.yaml ``` <!-- ```hide kubectl wait pod registry --for condition=ready``` --> - Check the IP address allocated to the pod: ```bash kubectl get pod registry -o wide IP=$(kubectl get pod registry -o json | jq -r .status.podIP) ``` - Confirm that the registry is available on port 80: ```bash curl $IP/v2/_catalog ``` ] ??? :EN:- Managing application configuration :EN:- Exposing configuration with the downward API :EN:- Exposing configuration with Config Maps :FR:- Gérer la configuration des applications :FR:- Configuration au travers de la *downward API* :FR:- Configurer les applications avec des *Config Maps* .debug[[k8s/configuration.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/configuration.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-managing-secrets class: title Managing secrets .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-managing-configuration) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-4) | [Next part](#toc-managing-stacks-with-helm) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Managing secrets - Sometimes our code needs sensitive information: - passwords - API tokens - TLS keys - ... - *Secrets* can be used for that purpose - Secrets and ConfigMaps are very similar .debug[[k8s/secrets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/secrets.md)] --- ## Similarities between ConfigMap and Secrets - ConfigMap and Secrets are key-value maps (a Secret can contain zero, one, or many key-value pairs) - They can both be exposed with the downward API or volumes - They can both be created with YAML or with a CLI command (`kubectl create configmap` / `kubectl create secret`) .debug[[k8s/secrets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/secrets.md)] --- ## ConfigMap and Secrets are different resources - They can have different RBAC permissions (e.g. the default `view` role can read ConfigMaps but not Secrets) - They indicate a different *intent*: *"You should use secrets for things which are actually secret like API keys, credentials, etc., and use config map for not-secret configuration data."* *"In the future there will likely be some differentiators for secrets like rotation or support for backing the secret API w/ HSMs, etc."* (Source: [the author of both features](https://stackoverflow.com/a/36925553/580281 )) .debug[[k8s/secrets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/secrets.md)] --- ## Secrets have an optional *type* - The type indicates which keys must exist in the secrets, for instance: `kubernetes.io/tls` requires `tls.crt` and `tls.key` `kubernetes.io/basic-auth` requires `username` and `password` `kubernetes.io/ssh-auth` requires `ssh-privatekey` `kubernetes.io/dockerconfigjson` requires `.dockerconfigjson` `kubernetes.io/service-account-token` requires `token`, `namespace`, `ca.crt` (the whole list is in [the documentation](https://kubernetes.io/docs/concepts/configuration/secret/#secret-types)) - This is merely for our (human) convenience: “Ah yes, this secret is a ...” .debug[[k8s/secrets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/secrets.md)] --- ## Accessing private repositories - Let's see how to access an image on a private registry! - These images are protected by a username + password (on some registries, it's token + password, but it's the same thing) - To access a private image, we need to: - create a secret - reference that secret in a Pod template - or reference that secret in a ServiceAccount used by a Pod .debug[[k8s/secrets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/secrets.md)] --- ## In practice - Let's try to access an image on a private registry! - image = docker-registry.enix.io/jpetazzo/private:latest - user = reader - password = VmQvqdtXFwXfyy4Jb5DR .lab[ - Create a Deployment using that image: ```bash kubectl create deployment priv \ --image=docker-registry.enix.io/jpetazzo/private ``` - Check that the Pod won't start: ```bash kubectl get pods --selector=app=priv ``` ] .debug[[k8s/secrets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/secrets.md)] --- ## Creating a secret - Let's create a secret with the information provided earlier .lab[ - Create the registry secret: ```bash kubectl create secret docker-registry enix \ --docker-server=docker-registry.enix.io \ --docker-username=reader \ --docker-password=VmQvqdtXFwXfyy4Jb5DR ``` ] Why do we have to specify the registry address? If we use multiple sets of credentials for different registries, it prevents leaking the credentials of one registry to *another* registry. .debug[[k8s/secrets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/secrets.md)] --- ## Using the secret - The first way to use a secret is to add it to `imagePullSecrets` (in the `spec` section of a Pod template) .lab[ - Patch the `priv` Deployment that we created earlier: ```bash kubectl patch deploy priv --patch=' spec: template: spec: imagePullSecrets: - name: enix ' ``` ] .debug[[k8s/secrets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/secrets.md)] --- ## Checking the results .lab[ - Confirm that our Pod can now start correctly: ```bash kubectl get pods --selector=app=priv ``` ] .debug[[k8s/secrets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/secrets.md)] --- ## Another way to use the secret - We can add the secret to the ServiceAccount - This is convenient to automatically use credentials for *all* pods (as long as they're using a specific ServiceAccount, of course) .lab[ - Add the secret to the ServiceAccount: ```bash kubectl patch serviceaccount default --patch=' imagePullSecrets: - name: enix ' ``` ] .debug[[k8s/secrets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/secrets.md)] --- ## Secrets are displayed with base64 encoding - When shown with e.g. `kubectl get secrets -o yaml`, secrets are base64-encoded - Likewise, when defining it with YAML, `data` values are base64-encoded - Example: ```yaml kind: Secret apiVersion: v1 metadata: name: pin-codes data: onetwothreefour: MTIzNA== zerozerozerozero: MDAwMA== ``` - Keep in mind that this is just *encoding*, not *encryption* - It is very easy to [automatically extract and decode secrets](https://medium.com/@mveritym/decoding-kubernetes-secrets-60deed7a96a3) .debug[[k8s/secrets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/secrets.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Using `stringData` - When creating a Secret, it is possible to bypass base64 - Just use `stringData` instead of `data`: ```yaml kind: Secret apiVersion: v1 metadata: name: pin-codes stringData: onetwothreefour: 1234 zerozerozerozero: 0000 ``` - It will show up as base64 if you `kubectl get -o yaml` - No `type` was specified, so it defaults to `Opaque` .debug[[k8s/secrets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/secrets.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Encryption at rest - It is possible to [encrypt secrets at rest](https://kubernetes.io/docs/tasks/administer-cluster/encrypt-data/) - This means that secrets will be safe if someone ... - steals our etcd servers - steals our backups - snoops the e.g. iSCSI link between our etcd servers and SAN - However, starting the API server will now require human intervention (to provide the decryption keys) - This is only for extremely regulated environments (military, nation states...) .debug[[k8s/secrets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/secrets.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Immutable ConfigMaps and Secrets - Since Kubernetes 1.19, it is possible to mark a ConfigMap or Secret as *immutable* ```bash kubectl patch configmap xyz --patch='{"immutable": true}' ``` - This brings performance improvements when using lots of ConfigMaps and Secrets (lots = tens of thousands) - Once a ConfigMap or Secret has been marked as immutable: - its content cannot be changed anymore - the `immutable` field can't be changed back either - the only way to change it is to delete and re-create it - Pods using it will have to be re-created as well ??? :EN:- Handling passwords and tokens safely :FR:- Manipulation de mots de passe, clés API etc. .debug[[k8s/secrets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/secrets.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-managing-stacks-with-helm class: title Managing stacks with Helm .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-managing-secrets) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-4) | [Next part](#toc-exercise--ingress) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Managing stacks with Helm - Helm is a (kind of!) package manager for Kubernetes - We can use it to: - find existing packages (called "charts") created by other folks - install these packages, configuring them for our particular setup - package our own things (for distribution or for internal use) - manage the lifecycle of these installs (rollback to previous version etc.) - It's a "CNCF graduate project", indicating a certain level of maturity (more on that later) .debug[[k8s/helm-intro.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/helm-intro.md)] --- ## From `kubectl run` to YAML - We can create resources with one-line commands (`kubectl run`, `kubectl create deployment`, `kubectl expose`...) - We can also create resources by loading YAML files (with `kubectl apply -f`, `kubectl create -f`...) - There can be multiple resources in a single YAML files (making them convenient to deploy entire stacks) - However, these YAML bundles often need to be customized (e.g.: number of replicas, image version to use, features to enable...) .debug[[k8s/helm-intro.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/helm-intro.md)] --- ## Beyond YAML - Very often, after putting together our first `app.yaml`, we end up with: - `app-prod.yaml` - `app-staging.yaml` - `app-dev.yaml` - instructions indicating to users "please tweak this and that in the YAML" - That's where using something like [CUE](https://github.com/cuelang/cue/blob/v0.3.2/doc/tutorial/kubernetes/README.md), [Kustomize](https://kustomize.io/), or [Helm](https://helm.sh/) can help! - Now we can do something like this: ```bash helm install app ... --set this.parameter=that.value ``` .debug[[k8s/helm-intro.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/helm-intro.md)] --- ## Other features of Helm - With Helm, we create "charts" - These charts can be used internally or distributed publicly - Public charts can be indexed through the [Artifact Hub](https://artifacthub.io/) - This gives us a way to find and install other folks' charts - Helm also gives us ways to manage the lifecycle of what we install: - keep track of what we have installed - upgrade versions, change parameters, roll back, uninstall - Furthermore, even if it's not "the" standard, it's definitely "a" standard! .debug[[k8s/helm-intro.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/helm-intro.md)] --- ## CNCF graduation status - On April 30th 2020, Helm was the 10th project to *graduate* within the CNCF 🎉 (alongside Containerd, Prometheus, and Kubernetes itself) - This is an acknowledgement by the CNCF for projects that *demonstrate thriving adoption, an open governance process, <br/> and a strong commitment to community, sustainability, and inclusivity.* - See [CNCF announcement](https://www.cncf.io/announcement/2020/04/30/cloud-native-computing-foundation-announces-helm-graduation/) and [Helm announcement](https://helm.sh/blog/celebrating-helms-cncf-graduation/) .debug[[k8s/helm-intro.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/helm-intro.md)] --- ## Helm concepts - `helm` is a CLI tool - It is used to find, install, upgrade *charts* - A chart is an archive containing templatized YAML bundles - Charts are versioned - Charts can be stored on private or public repositories .debug[[k8s/helm-intro.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/helm-intro.md)] --- ## Differences between charts and packages - A package (deb, rpm...) contains binaries, libraries, etc. - A chart contains YAML manifests (the binaries, libraries, etc. are in the images referenced by the chart) - On most distributions, a package can only be installed once (installing another version replaces the installed one) - A chart can be installed multiple times - Each installation is called a *release* - This allows to install e.g. 10 instances of MongoDB (with potentially different versions and configurations) .debug[[k8s/helm-intro.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/helm-intro.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Wait a minute ... *But, on my Debian system, I have Python 2 **and** Python 3. <br/> Also, I have multiple versions of the Postgres database engine!* Yes! But they have different package names: - `python2.7`, `python3.8` - `postgresql-10`, `postgresql-11` Good to know: the Postgres package in Debian includes provisions to deploy multiple Postgres servers on the same system, but it's an exception (and it's a lot of work done by the package maintainer, not by the `dpkg` or `apt` tools). .debug[[k8s/helm-intro.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/helm-intro.md)] --- ## Helm 2 vs Helm 3 - Helm 3 was released [November 13, 2019](https://helm.sh/blog/helm-3-released/) - Charts remain compatible between Helm 2 and Helm 3 - The CLI is very similar (with minor changes to some commands) - The main difference is that Helm 2 uses `tiller`, a server-side component - Helm 3 doesn't use `tiller` at all, making it simpler (yay!) .debug[[k8s/helm-intro.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/helm-intro.md)] --- class: extra-details ## With or without `tiller` - With Helm 3: - the `helm` CLI communicates directly with the Kubernetes API - it creates resources (deployments, services...) with our credentials - With Helm 2: - the `helm` CLI communicates with `tiller`, telling `tiller` what to do - `tiller` then communicates with the Kubernetes API, using its own credentials - This indirect model caused significant permissions headaches (`tiller` required very broad permissions to function) - `tiller` was removed in Helm 3 to simplify the security aspects .debug[[k8s/helm-intro.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/helm-intro.md)] --- ## Installing Helm - If the `helm` CLI is not installed in your environment, install it .lab[ - Check if `helm` is installed: ```bash helm ``` - If it's not installed, run the following command: ```bash curl https://raw.githubusercontent.com/kubernetes/helm/master/scripts/get-helm-3 \ | bash ``` ] (To install Helm 2, replace `get-helm-3` with `get`.) .debug[[k8s/helm-intro.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/helm-intro.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Only if using Helm 2 ... - We need to install Tiller and give it some permissions - Tiller is composed of a *service* and a *deployment* in the `kube-system` namespace - They can be managed (installed, upgraded...) with the `helm` CLI .lab[ - Deploy Tiller: ```bash helm init ``` ] At the end of the install process, you will see: ``` Happy Helming! ``` .debug[[k8s/helm-intro.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/helm-intro.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Only if using Helm 2 ... - Tiller needs permissions to create Kubernetes resources - In a more realistic deployment, you might create per-user or per-team service accounts, roles, and role bindings .lab[ - Grant `cluster-admin` role to `kube-system:default` service account: ```bash kubectl create clusterrolebinding add-on-cluster-admin \ --clusterrole=cluster-admin --serviceaccount=kube-system:default ``` ] (Defining the exact roles and permissions on your cluster requires a deeper knowledge of Kubernetes' RBAC model. The command above is fine for personal and development clusters.) .debug[[k8s/helm-intro.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/helm-intro.md)] --- ## Charts and repositories - A *repository* (or repo in short) is a collection of charts - It's just a bunch of files (they can be hosted by a static HTTP server, or on a local directory) - We can add "repos" to Helm, giving them a nickname - The nickname is used when referring to charts on that repo (for instance, if we try to install `hello/world`, that means the chart `world` on the repo `hello`; and that repo `hello` might be something like https://blahblah.hello.io/charts/) .debug[[k8s/helm-intro.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/helm-intro.md)] --- class: extra-details ## How to find charts, the old way - Helm 2 came with one pre-configured repo, the "stable" repo (located at https://charts.helm.sh/stable) - Helm 3 doesn't have any pre-configured repo - The "stable" repo mentioned above is now being deprecated - The new approach is to have fully decentralized repos - Repos can be indexed in the Artifact Hub (which supersedes the Helm Hub) .debug[[k8s/helm-intro.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/helm-intro.md)] --- ## How to find charts, the new way - Go to the [Artifact Hub](https://artifacthub.io/packages/search?kind=0) (https://artifacthub.io) - Or use `helm search hub ...` from the CLI - Let's try to find a Helm chart for something called "OWASP Juice Shop"! (it is a famous demo app used in security challenges) .debug[[k8s/helm-intro.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/helm-intro.md)] --- ## Finding charts from the CLI - We can use `helm search hub <keyword>` .lab[ - Look for the OWASP Juice Shop app: ```bash helm search hub owasp juice ``` - Since the URLs are truncated, try with the YAML output: ```bash helm search hub owasp juice -o yaml ``` ] Then go to → https://artifacthub.io/packages/helm/seccurecodebox/juice-shop .debug[[k8s/helm-intro.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/helm-intro.md)] --- ## Finding charts on the web - We can also use the Artifact Hub search feature .lab[ - Go to https://artifacthub.io/ - In the search box on top, enter "owasp juice" - Click on the "juice-shop" result (not "multi-juicer" or "juicy-ctf") ] .debug[[k8s/helm-intro.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/helm-intro.md)] --- ## Installing the chart - Click on the "Install" button, it will show instructions .lab[ - First, add the repository for that chart: ```bash helm repo add juice https://charts.securecodebox.io ``` - Then, install the chart: ```bash helm install my-juice-shop juice/juice-shop ``` ] Note: it is also possible to install directly a chart, with `--repo https://...` .debug[[k8s/helm-intro.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/helm-intro.md)] --- ## Charts and releases - "Installing a chart" means creating a *release* - In the previous example, the release was named "my-juice-shop" - We can also use `--generate-name` to ask Helm to generate a name for us .lab[ - List the releases: ```bash helm list ``` - Check that we have a `my-juice-shop-...` Pod up and running: ```bash kubectl get pods ``` ] .debug[[k8s/helm-intro.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/helm-intro.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Searching and installing with Helm 2 - Helm 2 doesn't have support for the Helm Hub - The `helm search` command only takes a search string argument (e.g. `helm search juice-shop`) - With Helm 2, the name is optional: `helm install juice/juice-shop` will automatically generate a name `helm install --name my-juice-shop juice/juice-shop` will specify a name .debug[[k8s/helm-intro.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/helm-intro.md)] --- ## Viewing resources of a release - This specific chart labels all its resources with a `release` label - We can use a selector to see these resources .lab[ - List all the resources created by this release: ```bash kubectl get all --selector=app.kubernetes.io/instance=my-juice-shop ``` ] Note: this label wasn't added automatically by Helm. <br/> It is defined in that chart. In other words, not all charts will provide this label. .debug[[k8s/helm-intro.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/helm-intro.md)] --- ## Configuring a release - By default, `juice/juice-shop` creates a service of type `ClusterIP` - We would like to change that to a `NodePort` - We could use `kubectl edit service my-juice-shop`, but ... ... our changes would get overwritten next time we update that chart! - Instead, we are going to *set a value* - Values are parameters that the chart can use to change its behavior - Values have default values - Each chart is free to define its own values and their defaults .debug[[k8s/helm-intro.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/helm-intro.md)] --- ## Checking possible values - We can inspect a chart with `helm show` or `helm inspect` .lab[ - Look at the README for the app: ```bash helm show readme juice/juice-shop ``` - Look at the values and their defaults: ```bash helm show values juice/juice-shop ``` ] The `values` may or may not have useful comments. The `readme` may or may not have (accurate) explanations for the values. (If we're unlucky, there won't be any indication about how to use the values!) .debug[[k8s/helm-intro.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/helm-intro.md)] --- ## Setting values - Values can be set when installing a chart, or when upgrading it - We are going to update `my-juice-shop` to change the type of the service .lab[ - Update `my-juice-shop`: ```bash helm upgrade my-juice-shop juice/my-juice-shop \ --set service.type=NodePort ``` ] Note that we have to specify the chart that we use (`juice/my-juice-shop`), even if we just want to update some values. We can set multiple values. If we want to set many values, we can use `-f`/`--values` and pass a YAML file with all the values. All unspecified values will take the default values defined in the chart. .debug[[k8s/helm-intro.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/helm-intro.md)] --- ## Connecting to the Juice Shop - Let's check the app that we just installed .lab[ - Check the node port allocated to the service: ```bash kubectl get service my-juice-shop PORT=$(kubectl get service my-juice-shop -o jsonpath={..nodePort}) ``` - Connect to it: ```bash curl localhost:$PORT/ ``` ] ??? :EN:- Helm concepts :EN:- Installing software with Helm :EN:- Helm 2, Helm 3, and the Helm Hub :FR:- Fonctionnement général de Helm :FR:- Installer des composants via Helm :FR:- Helm 2, Helm 3, et le *Helm Hub* :T: Getting started with Helm and its concepts :Q: Which comparison is the most adequate? :A: Helm is a firewall, charts are access lists :A: ✔️Helm is a package manager, charts are packages :A: Helm is an artefact repository, charts are artefacts :A: Helm is a CI/CD platform, charts are CI/CD pipelines :Q: What's required to distribute a Helm chart? :A: A Helm commercial license :A: A Docker registry :A: An account on the Helm Hub :A: ✔️An HTTP server .debug[[k8s/helm-intro.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/helm-intro.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-exercise--ingress class: title Exercise — Ingress .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-managing-stacks-with-helm) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-4) | [Next part](#toc-authentication-and-authorization) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Exercise — Ingress - We want to expose a couple of web apps through an ingress controller - This will require: - the web apps (e.g. two instances of `jpetazzo/color`) - an ingress controller - an ingress resource .debug[[exercises/ingress-details.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/exercises/ingress-details.md)] --- ## Different scenarios We will use a different deployment mechanism depending on the cluster that we have: - Managed cluster with working `LoadBalancer` Services - Local development cluster - Cluster without `LoadBalancer` Services (e.g. deployed with `kubeadm`) .debug[[exercises/ingress-details.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/exercises/ingress-details.md)] --- ## The apps - The web apps will be deployed similarly, regardless of the scenario - Let's start by deploying two web apps, e.g.: a Deployment called `blue` and another called `green`, using image `jpetazzo/color` - Expose them with two `ClusterIP` Services .debug[[exercises/ingress-details.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/exercises/ingress-details.md)] --- ## Scenario "classic cloud Kubernetes" *Difficulty: easy* For this scenario, we need a cluster with working `LoadBalancer` Services. (For instance, a managed Kubernetes cluster from a cloud provider.) We suggest to use "Ingress NGINX" with its default settings. It can be installed with `kubectl apply` or with `helm`. Both methods are described in [the documentation][ingress-nginx-deploy]. We want our apps to be available on e.g. http://X.X.X.X/blue and http://X.X.X.X/green <br/> (where X.X.X.X is the IP address of the `LoadBalancer` allocated by Ingress NGINX). [ingress-nginx-deploy]: https://kubernetes.github.io/ingress-nginx/deploy/ .debug[[exercises/ingress-details.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/exercises/ingress-details.md)] --- ## Scenario "local development cluster" *Difficulty: easy-hard (depends on the type of cluster!)* For this scenario, we want to use a local cluster like KinD, minikube, etc. We suggest to use "Ingress NGINX" again, like for the previous scenario. Furthermore, we want to use `localdev.me`. We want our apps to be available on e.g. `blue.localdev.me` and `green.localdev.me`. The difficulty is to ensure that `localhost:80` will map to the ingress controller. (See next slide for hints!) .debug[[exercises/ingress-details.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/exercises/ingress-details.md)] --- ## Hints - With clusters like Docker Desktop, the first `LoadBalancer` service uses `localhost` (if the ingress controller is the first `LoadBalancer` service, we're all set!) - With clusters like K3D and KinD, it is possible to define extra port mappings (and map e.g. `localhost:80` to port 30080 on the node; then use that as a `NodePort`) .debug[[exercises/ingress-details.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/exercises/ingress-details.md)] --- ## Scenario "on premises cluster", take 1 *Difficulty: easy* For this scenario, we need a cluster with nodes that are publicly accessible. We want to deploy the ingress controller so that it listens on port 80 on all nodes. This can be done e.g. with the manifests in [k8s/traefik.yaml](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/master/k8s/traefik.yaml). We want our apps to be available on e.g. http://X.X.X.X/blue and http://X.X.X.X/green <br/> (where X.X.X.X is the IP address of any of our nodes). .debug[[exercises/ingress-details.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/exercises/ingress-details.md)] --- ## Scenario "on premises cluster", take 2 *Difficulty: medium* We want to deploy the ingress controller so that it listens on port 80 on all nodes. But this time, we want to use a Helm chart to install the ingress controller. We can use either the Ingress NGINX Helm chart, or the Traefik Helm chart. Test with an untainted node first. Feel free to make it work on tainted nodes (e.g. control plane nodes) later. .debug[[exercises/ingress-details.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/exercises/ingress-details.md)] --- ## Scenario "on premises cluster", take 3 *Difficulty: hard* This is similar to the previous scenario, but with two significant changes: 1. We only want to run the ingress controller on nodes that have the role `ingress`. 2. We don't want to use `hostNetwork`, but a list of `externalIPs` instead. .debug[[exercises/ingress-details.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/exercises/ingress-details.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-authentication-and-authorization class: title Authentication and authorization .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-exercise--ingress) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-5) | [Next part](#toc-resource-limits) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Authentication and authorization - In this section, we will: - define authentication and authorization - explain how they are implemented in Kubernetes - talk about tokens, certificates, service accounts, RBAC ... - But first: why do we need all this? .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## The need for fine-grained security - The Kubernetes API should only be available for identified users - we don't want "guest access" (except in very rare scenarios) - we don't want strangers to use our compute resources, delete our apps ... - our keys and passwords should not be exposed to the public - Users will often have different access rights - cluster admin (similar to UNIX "root") can do everything - developer might access specific resources, or a specific namespace - supervision might have read only access to *most* resources .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Example: custom HTTP load balancer - Let's imagine that we have a custom HTTP load balancer for multiple apps - Each app has its own *Deployment* resource - By default, the apps are "sleeping" and scaled to zero - When a request comes in, the corresponding app gets woken up - After some inactivity, the app is scaled down again - This HTTP load balancer needs API access (to scale up/down) - What if *a wild vulnerability appears*? .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Consequences of vulnerability - If the HTTP load balancer has the same API access as we do: *full cluster compromise (easy data leak, cryptojacking...)* - If the HTTP load balancer has `update` permissions on the Deployments: *defacement (easy), MITM / impersonation (medium to hard)* - If the HTTP load balancer only has permission to `scale` the Deployments: *denial-of-service* - All these outcomes are bad, but some are worse than others .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Definitions - Authentication = verifying the identity of a person On a UNIX system, we can authenticate with login+password, SSH keys ... - Authorization = listing what they are allowed to do On a UNIX system, this can include file permissions, sudoer entries ... - Sometimes abbreviated as "authn" and "authz" - In good modular systems, these things are decoupled (so we can e.g. change a password or SSH key without having to reset access rights) .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Authentication in Kubernetes - When the API server receives a request, it tries to authenticate it (it examines headers, certificates... anything available) - Many authentication methods are available and can be used simultaneously (we will see them on the next slide) - It's the job of the authentication method to produce: - the user name - the user ID - a list of groups - The API server doesn't interpret these; that'll be the job of *authorizers* .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Authentication methods - TLS client certificates (that's the default for clusters provisioned with `kubeadm`) - Bearer tokens (a secret token in the HTTP headers of the request) - [HTTP basic auth](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basic_access_authentication) (carrying user and password in an HTTP header; [deprecated since Kubernetes 1.19](https://github.com/kubernetes/kubernetes/pull/89069)) - Authentication proxy (sitting in front of the API and setting trusted headers) .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Anonymous requests - If any authentication method *rejects* a request, it's denied (`401 Unauthorized` HTTP code) - If a request is neither rejected nor accepted by anyone, it's anonymous - the user name is `system:anonymous` - the list of groups is `[system:unauthenticated]` - By default, the anonymous user can't do anything (that's what you get if you just `curl` the Kubernetes API) .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Authentication with TLS certificates - Enabled in almost all Kubernetes deployments - The user name is indicated by the `CN` in the client certificate - The groups are indicated by the `O` fields in the client certificate - From the point of view of the Kubernetes API, users do not exist (i.e. there is no resource with `kind: User`) - The Kubernetes API can be set up to use your custom CA to validate client certs .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Authentication for kubelet - In most clusters, kubelets authenticate using certificates (`O=system:nodes`, `CN=system:node:name-of-the-node`) - The Kubernetes API can act as a CA (by wrapping an X509 CSR into a CertificateSigningRequest resource) - This enables kubelets to renew their own certificates - It can also be used to issue user certificates (but it lacks flexibility; e.g. validity can't be customized) .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## User certificates in practice - The Kubernetes API server does not support certificate revocation (see issue [#18982](https://github.com/kubernetes/kubernetes/issues/18982)) - As a result, we don't have an easy way to terminate someone's access (if their key is compromised, or they leave the organization) - Issue short-lived certificates if you use them to authenticate users! (short-lived = a few hours) - This can be facilitated by e.g. Vault, cert-manager... .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## What if a certificate is compromised? - Option 1: wait for the certificate to expire (which is why short-lived certs are convenient!) - Option 2: remove access from that certificate's user and groups - if that user was `bob.smith`, create a new user `bob.smith.2` - if Bob was in groups `dev`, create a new group `dev.2` - let's agree that this is not a great solution! - Option 3: re-create a new CA and re-issue all certificates - let's agree that this is an even worse solution! .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Authentication with tokens - Tokens are passed as HTTP headers: `Authorization: Bearer and-then-here-comes-the-token` - Tokens can be validated through a number of different methods: - static tokens hard-coded in a file on the API server - [bootstrap tokens](https://kubernetes.io/docs/reference/access-authn-authz/bootstrap-tokens/) (special case to create a cluster or join nodes) - [OpenID Connect tokens](https://kubernetes.io/docs/reference/access-authn-authz/authentication/#openid-connect-tokens) (to delegate authentication to compatible OAuth2 providers) - service accounts (these deserve more details, coming right up!) .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Service accounts - A service account is a user that exists in the Kubernetes API (it is visible with e.g. `kubectl get serviceaccounts`) - Service accounts can therefore be created / updated dynamically (they don't require hand-editing a file and restarting the API server) - A service account can be associated with a set of secrets (the kind that you can view with `kubectl get secrets`) - Service accounts are generally used to grant permissions to applications, services... (as opposed to humans) .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Service account tokens evolution - In Kubernetes 1.21 and above, pods use *bound service account tokens*: - these tokens are *bound* to a specific object (e.g. a Pod) - they are automatically invalidated when the object is deleted - these tokens also expire quickly (e.g. 1 hour) and gets rotated automatically - In Kubernetes 1.24 and above, unbound tokens aren't created automatically - before 1.24, we would see unbound tokens with `kubectl get secrets` - with 1.24 and above, these tokens can be created with `kubectl create token` - ...or with a Secret with the right [type and annotation][create-token] [create-token]: https://kubernetes.io/docs/reference/access-authn-authz/service-accounts-admin/#create-token .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Checking our authentication method - Let's check our kubeconfig file - Do we have a certificate, a token, or something else? .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Inspecting a certificate If we have a certificate, let's use the following command: ```bash kubectl config view \ --raw \ -o json \ | jq -r .users[0].user[\"client-certificate-data\"] \ | openssl base64 -d -A \ | openssl x509 -text \ | grep Subject: ``` This command will show the `CN` and `O` fields for our certificate. .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Breaking down the command - `kubectl config view` shows the Kubernetes user configuration - `--raw` includes certificate information (which shows as REDACTED otherwise) - `-o json` outputs the information in JSON format - `| jq ...` extracts the field with the user certificate (in base64) - `| openssl base64 -d -A` decodes the base64 format (now we have a PEM file) - `| openssl x509 -text` parses the certificate and outputs it as plain text - `| grep Subject:` shows us the line that interests us → We are user `kubernetes-admin`, in group `system:masters`. (We will see later how and why this gives us the permissions that we have.) .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Inspecting a token If we have a token, let's use the following command: ```bash kubectl config view \ --raw \ -o json \ | jq -r .users[0].user.token \ | base64 -d \ | cut -d. -f2 \ | base64 -d \ | jq . ``` If our token is a JWT / OIDC token, this command will show its content. .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Other authentication methods - Other types of tokens - these tokens are typically shorter than JWT or OIDC tokens - it is generally not possible to extract information from them - Plugins - some clusters use external `exec` plugins - these plugins typically use API keys to generate or obtain tokens - example: the AWS EKS authenticator works this way .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Token authentication in practice - We are going to list existing service accounts - Then we will extract the token for a given service account - And we will use that token to authenticate with the API .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Listing service accounts .lab[ - The resource name is `serviceaccount` or `sa` for short: ```bash kubectl get sa ``` ] There should be just one service account in the default namespace: `default`. .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Finding the secret .lab[ - List the secrets for the `default` service account: ```bash kubectl get sa default -o yaml SECRET=$(kubectl get sa default -o json | jq -r .secrets[0].name) ``` ] It should be named `default-token-XXXXX`. When running Kubernetes 1.24 and above, this Secret won't exist. <br/> Instead, create a token with `kubectl create token default`. .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Extracting the token - The token is stored in the secret, wrapped with base64 encoding .lab[ - View the secret: ```bash kubectl get secret $SECRET -o yaml ``` - Extract the token and decode it: ```bash TOKEN=$(kubectl get secret $SECRET -o json \ | jq -r .data.token | openssl base64 -d -A) ``` ] .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Using the token - Let's send a request to the API, without and with the token .lab[ - Find the ClusterIP for the `kubernetes` service: ```bash kubectl get svc kubernetes API=$(kubectl get svc kubernetes -o json | jq -r .spec.clusterIP) ``` - Connect without the token: ```bash curl -k https://$API ``` - Connect with the token: ```bash curl -k -H "Authorization: Bearer $TOKEN" https://$API ``` ] .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Results - In both cases, we will get a "Forbidden" error - Without authentication, the user is `system:anonymous` - With authentication, it is shown as `system:serviceaccount:default:default` - The API "sees" us as a different user - But neither user has any rights, so we can't do nothin' - Let's change that! .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Authorization in Kubernetes - There are multiple ways to grant permissions in Kubernetes, called [authorizers](https://kubernetes.io/docs/reference/access-authn-authz/authorization/#authorization-modules): - [Node Authorization](https://kubernetes.io/docs/reference/access-authn-authz/node/) (used internally by kubelet; we can ignore it) - [Attribute-based access control](https://kubernetes.io/docs/reference/access-authn-authz/abac/) (powerful but complex and static; ignore it too) - [Webhook](https://kubernetes.io/docs/reference/access-authn-authz/webhook/) (each API request is submitted to an external service for approval) - [Role-based access control](https://kubernetes.io/docs/reference/access-authn-authz/rbac/) (associates permissions to users dynamically) - The one we want is the last one, generally abbreviated as RBAC .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Role-based access control - RBAC allows to specify fine-grained permissions - Permissions are expressed as *rules* - A rule is a combination of: - [verbs](https://kubernetes.io/docs/reference/access-authn-authz/authorization/#determine-the-request-verb) like create, get, list, update, delete... - resources (as in "API resource," like pods, nodes, services...) - resource names (to specify e.g. one specific pod instead of all pods) - in some case, [subresources](https://kubernetes.io/docs/reference/access-authn-authz/rbac/#referring-to-resources) (e.g. logs are subresources of pods) .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Listing all possible verbs - The Kubernetes API is self-documented - We can ask it which resources, subresources, and verb exist - One way to do this is to use: - `kubectl get --raw /api/v1` (for core resources with `apiVersion: v1`) - `kubectl get --raw /apis/<group>/<version>` (for other resources) - The JSON response can be formatted with e.g. `jq` for readability .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Examples - List all verbs across all `v1` resources ```bash kubectl get --raw /api/v1 | jq -r .resources[].verbs[] | sort -u ``` - List all resources and subresources in `apps/v1` ```bash kubectl get --raw /apis/apps/v1 | jq -r .resources[].name ``` - List which verbs are available on which resources in `networking.k8s.io` ```bash kubectl get --raw /apis/networking.k8s.io/v1 | \ jq -r '.resources[] | .name + ": " + (.verbs | join(", "))' ``` .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## From rules to roles to rolebindings - A *role* is an API object containing a list of *rules* Example: role "external-load-balancer-configurator" can: - [list, get] resources [endpoints, services, pods] - [update] resources [services] - A *rolebinding* associates a role with a user Example: rolebinding "external-load-balancer-configurator": - associates user "external-load-balancer-configurator" - with role "external-load-balancer-configurator" - Yes, there can be users, roles, and rolebindings with the same name - It's a good idea for 1-1-1 bindings; not so much for 1-N ones .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Cluster-scope permissions - API resources Role and RoleBinding are for objects within a namespace - We can also define API resources ClusterRole and ClusterRoleBinding - These are a superset, allowing us to: - specify actions on cluster-wide objects (like nodes) - operate across all namespaces - We can create Role and RoleBinding resources within a namespace - ClusterRole and ClusterRoleBinding resources are global .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Pods and service accounts - A pod can be associated with a service account - by default, it is associated with the `default` service account - as we saw earlier, this service account has no permissions anyway - The associated token is exposed to the pod's filesystem (in `/var/run/secrets/kubernetes.io/serviceaccount/token`) - Standard Kubernetes tooling (like `kubectl`) will look for it there - So Kubernetes tools running in a pod will automatically use the service account .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## In practice - We are going to run a pod - This pod will use the default service account of its namespace - We will check our API permissions (there shouldn't be any) - Then we will bind a role to the service account - We will check that we were granted the corresponding permissions .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Running a pod - We'll use [Nixery](https://nixery.dev/) to run a pod with `curl` and `kubectl` - Nixery automatically generates images with the requested packages .lab[ - Run our pod: ```bash kubectl run eyepod --rm -ti --restart=Never \ --image nixery.dev/shell/curl/kubectl -- bash ``` ] .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Checking our permissions - Normally, at this point, we don't have any API permission .lab[ - Check our permissions with `kubectl`: ```bash kubectl get pods ``` ] - We should get a message telling us that our service account doesn't have permissions to list "pods" in the current namespace - We can also make requests to the API server directly (use `kubectl -v6` to see the exact request URI!) .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Binding a role to the service account - Binding a role = creating a *rolebinding* object - We will call that object `can-view` (but again, we could call it `view` or whatever we like) .lab[ - Create the new role binding: ```bash kubectl create rolebinding can-view \ --clusterrole=view \ --serviceaccount=default:default ``` ] It's important to note a couple of details in these flags... .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Roles vs Cluster Roles - We used `--clusterrole=view` - What would have happened if we had used `--role=view`? - we would have bound the role `view` from the local namespace <br/>(instead of the cluster role `view`) - the command would have worked fine (no error) - but later, our API requests would have been denied - This is a deliberate design decision (we can reference roles that don't exist, and create/update them later) .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Users vs Service Accounts - We used `--serviceaccount=default:default` - What would have happened if we had used `--user=default:default`? - we would have bound the role to a user instead of a service account - again, the command would have worked fine (no error) - ...but our API requests would have been denied later - What's about the `default:` prefix? - that's the namespace of the service account - yes, it could be inferred from context, but... `kubectl` requires it .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Checking our new permissions - We should be able to *view* things, but not to *edit* them .lab[ - Check our permissions with `kubectl`: ```bash kubectl get pods ``` - Try to create something: ```bash kubectl create deployment can-i-do-this --image=nginx ``` - Exit the container with `exit` or `^D` <!-- ```key ^D``` --> ] .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: extra-details ## `kubectl run --serviceaccount` - `kubectl run` also has a `--serviceaccount` flag - ...But it's supposed to be deprecated "soon" (see [kubernetes/kubernetes#99732](https://github.com/kubernetes/kubernetes/pull/99732) for details) - It's possible to specify the service account with an override: ```bash kubectl run my-pod -ti --image=alpine --restart=Never \ --overrides='{ "spec": { "serviceAccountName" : "my-service-account" } }' ``` .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## `kubectl auth` and other CLI tools - The `kubectl auth can-i` command can tell us: - if we can perform an action - if someone else can perform an action - what actions we can perform - There are also other very useful tools to work with RBAC - Let's do a quick review! .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## `kubectl auth can-i dothis onthat` - These commands will give us a `yes`/`no` answer: ```bash kubectl auth can-i list nodes kubectl auth can-i create pods kubectl auth can-i get pod/name-of-pod kubectl auth can-i get /url-fragment-of-api-request/ kubectl auth can-i '*' services kubectl auth can-i get coffee kubectl auth can-i drink coffee ``` - The RBAC system is flexible - We can check permissions on resources that don't exist yet (e.g. CRDs) - We can check permissions for arbitrary actions .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## `kubectl auth can-i ... --as someoneelse` - We can check permissions on behalf of other users ```bash kubectl auth can-i list nodes \ --as some-user kubectl auth can-i list nodes \ --as system:serviceaccount:<namespace>:<name-of-service-account> ``` - We can also use `--as-group` to check permissions for members of a group - `--as` and `--as-group` leverage the *impersonation API* - These flags can be used with many other `kubectl` commands (not just `auth can-i`) .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## `kubectl auth can-i --list` - We can list the actions that are available to us: ```bash kubectl auth can-i --list ``` - ... Or to someone else (with `--as SomeOtherUser`) - This is very useful to check users or service accounts for overly broad permissions (or when looking for ways to exploit a security vulnerability!) - To learn more about Kubernetes attacks and threat models around RBAC: 📽️ [Hacking into Kubernetes Security for Beginners](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mLsCm9GVIQg) by [Ellen Körbes](https://twitter.com/ellenkorbes) and [Tabitha Sable](https://twitter.com/TabbySable) .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Other useful tools - For auditing purposes, sometimes we want to know who can perform which actions - There are a few tools to help us with that, available as `kubectl` plugins: - `kubectl who-can` / [kubectl-who-can](https://github.com/aquasecurity/kubectl-who-can) by Aqua Security - `kubectl access-matrix` / [Rakkess (Review Access)](https://github.com/corneliusweig/rakkess) by Cornelius Weig - `kubectl rbac-lookup` / [RBAC Lookup](https://github.com/FairwindsOps/rbac-lookup) by FairwindsOps - `kubectl rbac-tool` / [RBAC Tool](https://github.com/alcideio/rbac-tool) by insightCloudSec - `kubectl` plugins can be installed and managed with `krew` - They can also be installed and executed as standalone programs .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Where does this `view` role come from? - Kubernetes defines a number of ClusterRoles intended to be bound to users - `cluster-admin` can do *everything* (think `root` on UNIX) - `admin` can do *almost everything* (except e.g. changing resource quotas and limits) - `edit` is similar to `admin`, but cannot view or edit permissions - `view` has read-only access to most resources, except permissions and secrets *In many situations, these roles will be all you need.* *You can also customize them!* .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Customizing the default roles - If you need to *add* permissions to these default roles (or others), <br/> you can do it through the [ClusterRole Aggregation](https://kubernetes.io/docs/reference/access-authn-authz/rbac/#aggregated-clusterroles) mechanism - This happens by creating a ClusterRole with the following labels: ```yaml metadata: labels: rbac.authorization.k8s.io/aggregate-to-admin: "true" rbac.authorization.k8s.io/aggregate-to-edit: "true" rbac.authorization.k8s.io/aggregate-to-view: "true" ``` - This ClusterRole permissions will be added to `admin`/`edit`/`view` respectively .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: extra-details ## When should we use aggregation? - By default, CRDs aren't included in `view` / `edit` / etc. (Kubernetes cannot guess which one are security sensitive and which ones are not) - If we edit `view` / `edit` / etc directly, our edits will conflict (imagine if we have two CRDs and they both provide a custom `view` ClusterRole) - Using aggregated roles lets us enrich the default roles without touching them .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: extra-details ## How aggregation works - The corresponding roles will have `aggregationRules` like this: ```yaml aggregationRule: clusterRoleSelectors: - matchLabels: rbac.authorization.k8s.io/aggregate-to-view: "true" ``` - We can define our own custom roles with their own aggregation rules .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Where do our permissions come from? - When interacting with the Kubernetes API, we are using a client certificate - We saw previously that this client certificate contained: `CN=kubernetes-admin` and `O=system:masters` - Let's look for these in existing ClusterRoleBindings: ```bash kubectl get clusterrolebindings -o yaml | grep -e kubernetes-admin -e system:masters ``` (`system:masters` should show up, but not `kubernetes-admin`.) - Where does this match come from? .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: extra-details ## The `system:masters` group - If we eyeball the output of `kubectl get clusterrolebindings -o yaml`, we'll find out! - It is in the `cluster-admin` binding: ```bash kubectl describe clusterrolebinding cluster-admin ``` - This binding associates `system:masters` with the cluster role `cluster-admin` - And the `cluster-admin` is, basically, `root`: ```bash kubectl describe clusterrole cluster-admin ``` .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## `list` vs. `get` ⚠️ `list` grants read permissions to resources! - It's not possible to give permission to list resources without also reading them - This has implications for e.g. Secrets (if a controller needs to be able to enumerate Secrets, it will be able to read them) ??? :EN:- Authentication and authorization in Kubernetes :EN:- Authentication with tokens and certificates :EN:- Authorization with RBAC (Role-Based Access Control) :EN:- Restricting permissions with Service Accounts :EN:- Working with Roles, Cluster Roles, Role Bindings, etc. :FR:- Identification et droits d'accès dans Kubernetes :FR:- Mécanismes d'identification par jetons et certificats :FR:- Le modèle RBAC *(Role-Based Access Control)* :FR:- Restreindre les permissions grâce aux *Service Accounts* :FR:- Comprendre les *Roles*, *Cluster Roles*, *Role Bindings*, etc. .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-resource-limits class: title Resource Limits .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-authentication-and-authorization) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-5) | [Next part](#toc-defining-min-max-and-default-resources) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Resource Limits - We can attach resource indications to our pods (or rather: to the *containers* in our pods) - We can specify *limits* and/or *requests* - We can specify quantities of CPU and/or memory .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## CPU vs memory - CPU is a *compressible resource* - it can be preempted immediately without adverse effect - if we have N CPU and need 2N, we run at 50% speed - Memory is an *incompressible resource* - it needs to be swapped out to be reclaimed; and this is costly - if we have N GB RAM and need 2N, we might run at... 0.1% speed! - As a result, exceeding limits will have different consequences for CPU and memory .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- class: extra-details ## CPU limits implementation details - A container with a CPU limit will be "rationed" by the kernel - Every `cfs_period_us`, it will receive a CPU quota, like an "allowance" (that interval defaults to 100ms) - Once it has used its quota, it will be stalled until the next period - This can easily result in throttling for bursty workloads (see details on next slide) .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- class: extra-details ## A bursty example - Web service receives one request per minute - Each request takes 1 second of CPU - Average load: 1.66% - Let's say we set a CPU limit of 10% - This means CPU quotas of 10ms every 100ms - Obtaining the quota for 1 second of CPU will take 10 seconds - Observed latency will be 10 seconds (... actually 9.9s) instead of 1 second (real-life scenarios will of course be less extreme, but they do happen!) .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Multi-core scheduling details - Each core gets a small share of the container's CPU quota (this avoids locking and contention on the "global" quota for the container) - By default, the kernel distributes that quota to CPUs in 5ms increments (tunable with `kernel.sched_cfs_bandwidth_slice_us`) - If a containerized process (or thread) uses up its local CPU quota: *it gets more from the "global" container quota (if there's some left)* - If it "yields" (e.g. sleeps for I/O) before using its local CPU quota: *the quota is **soon** returned to the "global" container quota, **minus** 1ms* .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Low quotas on machines with many cores - The local CPU quota is not immediately returned to the global quota - this reduces locking and contention on the global quota - but this can cause starvation when many threads/processes become runnable - That 1ms that "stays" on the local CPU quota is often useful - if the thread/process becomes runnable, it can be scheduled immediately - again, this reduces locking and contention on the global quota - but if the thread/process doesn't become runnable, it is wasted! - this can become a huge problem on machines with many cores .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- class: extra-details ## CPU limits in a nutshell - Beware if you run small bursty workloads on machines with many cores! ("highly-threaded, user-interactive, non-cpu bound applications") - Check the `nr_throttled` and `throttled_time` metrics in `cpu.stat` - Possible solutions/workarounds: - be generous with the limits - make sure your kernel has the [appropriate patch](https://lkml.org/lkml/2019/5/17/581) - use [static CPU manager policy](https://kubernetes.io/docs/tasks/administer-cluster/cpu-management-policies/#static-policy) For more details, check [this blog post](https://erickhun.com/posts/kubernetes-faster-services-no-cpu-limits/) or these ones ([part 1](https://engineering.indeedblog.com/blog/2019/12/unthrottled-fixing-cpu-limits-in-the-cloud/), [part 2](https://engineering.indeedblog.com/blog/2019/12/cpu-throttling-regression-fix/)). .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Running low on memory - When the system runs low on memory, it starts to reclaim used memory (we talk about "memory pressure") - Option 1: free up some buffers and caches (fastest option; might affect performance if cache memory runs very low) - Option 2: swap, i.e. write to disk some memory of one process to give it to another (can have a huge negative impact on performance because disks are slow) - Option 3: terminate a process and reclaim all its memory (OOM or Out Of Memory Killer on Linux) .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Memory limits on Kubernetes - Kubernetes *does not support swap* (but it may support it in the future, thanks to [KEP 2400]) - If a container exceeds its memory *limit*, it gets killed immediately - If a node is overcommitted and under memory pressure, it will terminate some pods (see next slide for some details about what "overcommit" means here!) [KEP 2400]: https://github.com/kubernetes/enhancements/blob/master/keps/sig-node/2400-node-swap/README.md#implementation-history .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Overcommitting resources - *Limits* are "hard limits" (a container *cannot* exceed its limits) - a container exceeding its memory limit is killed - a container exceeding its CPU limit is throttled - On a given node, the sum of pod *limits* can be higher than the node size - *Requests* are used for scheduling purposes - a container can use more than its requested CPU or RAM amounts - a container using *less* than what it requested should never be killed or throttled - On a given node, the sum of pod *requests* cannot be higher than the node size .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Pod quality of service Each pod is assigned a QoS class (visible in `status.qosClass`). - If limits = requests: - as long as the container uses less than the limit, it won't be affected - if all containers in a pod have *(limits=requests)*, QoS is considered "Guaranteed" - If requests < limits: - as long as the container uses less than the request, it won't be affected - otherwise, it might be killed/evicted if the node gets overloaded - if at least one container has *(requests<limits)*, QoS is considered "Burstable" - If a pod doesn't have any request nor limit, QoS is considered "BestEffort" .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Quality of service impact - When a node is overloaded, BestEffort pods are killed first - Then, Burstable pods that exceed their requests - Burstable and Guaranteed pods below their requests are never killed (except if their node fails) - If we only use Guaranteed pods, no pod should ever be killed (as long as they stay within their limits) (Pod QoS is also explained in [this page](https://kubernetes.io/docs/tasks/configure-pod-container/quality-service-pod/) of the Kubernetes documentation and in [this blog post](https://medium.com/google-cloud/quality-of-service-class-qos-in-kubernetes-bb76a89eb2c6).) .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- class: extra-details ## CPU and RAM reservation - Kubernetes passes resources requests and limits to the container engine - The container engine applies these requests and limits with specific mechanisms - Example: on Linux, this is typically done with control groups aka cgroups - Most systems use cgroups v1, but cgroups v2 are slowly being rolled out (e.g. available in Ubuntu 22.04 LTS) - Cgroups v2 have new, interesting features for memory control: - ability to set "minimum" memory amounts (to effectively reserve memory) - better control on the amount of swap used by a container .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- class: extra-details ## What's the deal with swap? - With cgroups v1, it's not possible to disable swap for a cgroup (the closest option is to [reduce "swappiness"](https://unix.stackexchange.com/questions/77939/turning-off-swapping-for-only-one-process-with-cgroups)) - It is possible with cgroups v2 (see the [kernel docs](https://www.kernel.org/doc/html/latest/admin-guide/cgroup-v2.html) and the [fbatx docs](https://facebookmicrosites.github.io/cgroup2/docs/memory-controller.html#using-swap)) - Cgroups v2 aren't widely deployed yet - The architects of Kubernetes wanted to ensure that Guaranteed pods never swap - The simplest solution was to disable swap entirely - Kubelet will refuse to start if it detects that swap is enabled! .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Alternative point of view - Swap enables paging¹ of anonymous² memory - Even when swap is disabled, Linux will still page memory for: - executables, libraries - mapped files - Disabling swap *will reduce performance and available resources* - For a good time, read [kubernetes/kubernetes#53533](https://github.com/kubernetes/kubernetes/issues/53533) - Also read this [excellent blog post about swap](https://jvns.ca/blog/2017/02/17/mystery-swap/) ¹Paging: reading/writing memory pages from/to disk to reclaim physical memory ²Anonymous memory: memory that is not backed by files or blocks .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Enabling swap anyway - If you don't care that pods are swapping, you can enable swap - You will need to add the flag `--fail-swap-on=false` to kubelet (remember: it won't otherwise start if it detects that swap is enabled) .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Specifying resources - Resource requests are expressed at the *container* level - CPU is expressed in "virtual CPUs" (corresponding to the virtual CPUs offered by some cloud providers) - CPU can be expressed with a decimal value, or even a "milli" suffix (so 100m = 0.1) - Memory is expressed in bytes - Memory can be expressed with k, M, G, T, ki, Mi, Gi, Ti suffixes (corresponding to 10^3, 10^6, 10^9, 10^12, 2^10, 2^20, 2^30, 2^40) .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Specifying resources in practice This is what the spec of a Pod with resources will look like: ```yaml containers: - name: httpenv image: jpetazzo/httpenv resources: limits: memory: "100Mi" cpu: "100m" requests: memory: "100Mi" cpu: "10m" ``` This set of resources makes sure that this service won't be killed (as long as it stays below 100 MB of RAM), but allows its CPU usage to be throttled if necessary. .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Default values - If we specify a limit without a request: the request is set to the limit - If we specify a request without a limit: there will be no limit (which means that the limit will be the size of the node) - If we don't specify anything: the request is zero and the limit is the size of the node *Unless there are default values defined for our namespace!* .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## We need default resource values - If we do not set resource values at all: - the limit is "the size of the node" - the request is zero - This is generally *not* what we want - a container without a limit can use up all the resources of a node - if the request is zero, the scheduler can't make a smart placement decision - To address this, we can set default values for resources - This is done with a LimitRange object .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-defining-min-max-and-default-resources class: title Defining min, max, and default resources .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-resource-limits) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-5) | [Next part](#toc-namespace-quotas) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Defining min, max, and default resources - We can create LimitRange objects to indicate any combination of: - min and/or max resources allowed per pod - default resource *limits* - default resource *requests* - maximal burst ratio (*limit/request*) - LimitRange objects are namespaced - They apply to their namespace only .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## LimitRange example ```yaml apiVersion: v1 kind: LimitRange metadata: name: my-very-detailed-limitrange spec: limits: - type: Container min: cpu: "100m" max: cpu: "2000m" memory: "1Gi" default: cpu: "500m" memory: "250Mi" defaultRequest: cpu: "500m" ``` .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Example explanation The YAML on the previous slide shows an example LimitRange object specifying very detailed limits on CPU usage, and providing defaults on RAM usage. Note the `type: Container` line: in the future, it might also be possible to specify limits per Pod, but it's not [officially documented yet](https://github.com/kubernetes/website/issues/9585). .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## LimitRange details - LimitRange restrictions are enforced only when a Pod is created (they don't apply retroactively) - They don't prevent creation of e.g. an invalid Deployment or DaemonSet (but the pods will not be created as long as the LimitRange is in effect) - If there are multiple LimitRange restrictions, they all apply together (which means that it's possible to specify conflicting LimitRanges, <br/>preventing any Pod from being created) - If a LimitRange specifies a `max` for a resource but no `default`, <br/>that `max` value becomes the `default` limit too .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-namespace-quotas class: title Namespace quotas .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-defining-min-max-and-default-resources) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-5) | [Next part](#toc-limiting-resources-in-practice) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Namespace quotas - We can also set quotas per namespace - Quotas apply to the total usage in a namespace (e.g. total CPU limits of all pods in a given namespace) - Quotas can apply to resource limits and/or requests (like the CPU and memory limits that we saw earlier) - Quotas can also apply to other resources: - "extended" resources (like GPUs) - storage size - number of objects (number of pods, services...) .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Creating a quota for a namespace - Quotas are enforced by creating a ResourceQuota object - ResourceQuota objects are namespaced, and apply to their namespace only - We can have multiple ResourceQuota objects in the same namespace - The most restrictive values are used .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Limiting total CPU/memory usage - The following YAML specifies an upper bound for *limits* and *requests*: ```yaml apiVersion: v1 kind: ResourceQuota metadata: name: a-little-bit-of-compute spec: hard: requests.cpu: "10" requests.memory: 10Gi limits.cpu: "20" limits.memory: 20Gi ``` These quotas will apply to the namespace where the ResourceQuota is created. .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Limiting number of objects - The following YAML specifies how many objects of specific types can be created: ```yaml apiVersion: v1 kind: ResourceQuota metadata: name: quota-for-objects spec: hard: pods: 100 services: 10 secrets: 10 configmaps: 10 persistentvolumeclaims: 20 services.nodeports: 0 services.loadbalancers: 0 count/roles.rbac.authorization.k8s.io: 10 ``` (The `count/` syntax allows limiting arbitrary objects, including CRDs.) .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## YAML vs CLI - Quotas can be created with a YAML definition - ...Or with the `kubectl create quota` command - Example: ```bash kubectl create quota my-resource-quota --hard=pods=300,limits.memory=300Gi ``` - With both YAML and CLI form, the values are always under the `hard` section (there is no `soft` quota) .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Viewing current usage When a ResourceQuota is created, we can see how much of it is used: ``` kubectl describe resourcequota my-resource-quota Name: my-resource-quota Namespace: default Resource Used Hard -------- ---- ---- pods 12 100 services 1 5 services.loadbalancers 0 0 services.nodeports 0 0 ``` .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Advanced quotas and PriorityClass - Pods can have a *priority* - The priority is a number from 0 to 1000000000 (or even higher for system-defined priorities) - High number = high priority = "more important" Pod - Pods with a higher priority can *preempt* Pods with lower priority (= low priority pods will be *evicted* if needed) - Useful when mixing workloads in resource-constrained environments .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Setting the priority of a Pod - Create a PriorityClass (or use an existing one) - When creating the Pod, set the field `spec.priorityClassName` - If the field is not set: - if there is a PriorityClass with `globalDefault`, it is used - otherwise, the default priority will be zero .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- class: extra-details ## PriorityClass and ResourceQuotas - A ResourceQuota can include a list of *scopes* or a *scope selector* - In that case, the quota will only apply to the scoped resources - Example: limit the resources allocated to "high priority" Pods - In that case, make sure that the quota is created in every Namespace (or use *admission configuration* to enforce it) - See the [resource quotas documentation][quotadocs] for details [quotadocs]: https://kubernetes.io/docs/concepts/policy/resource-quotas/#resource-quota-per-priorityclass .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-limiting-resources-in-practice class: title Limiting resources in practice .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-namespace-quotas) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-5) | [Next part](#toc-checking-node-and-pod-resource-usage) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Limiting resources in practice - We have at least three mechanisms: - requests and limits per Pod - LimitRange per namespace - ResourceQuota per namespace - Let's see a simple recommendation to get started with resource limits .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Set a LimitRange - In each namespace, create a LimitRange object - Set a small default CPU request and CPU limit (e.g. "100m") - Set a default memory request and limit depending on your most common workload - for Java, Ruby: start with "1G" - for Go, Python, PHP, Node: start with "250M" - Set upper bounds slightly below your expected node size (80-90% of your node size, with at least a 500M memory buffer) .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Set a ResourceQuota - In each namespace, create a ResourceQuota object - Set generous CPU and memory limits (e.g. half the cluster size if the cluster hosts multiple apps) - Set generous objects limits - these limits should not be here to constrain your users - they should catch a runaway process creating many resources - example: a custom controller creating many pods .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Observe, refine, iterate - Observe the resource usage of your pods (we will see how in the next chapter) - Adjust individual pod limits - If you see trends: adjust the LimitRange (rather than adjusting every individual set of pod limits) - Observe the resource usage of your namespaces (with `kubectl describe resourcequota ...`) - Rinse and repeat regularly .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Underutilization - Remember: when assigning a pod to a node, the scheduler looks at *requests* (not at current utilization on the node) - If pods request resources but don't use them, this can lead to underutilization (because the scheduler will consider that the node is full and can't fit new pods) .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Viewing a namespace limits and quotas - `kubectl describe namespace` will display resource limits and quotas .lab[ - Try it out: ```bash kubectl describe namespace default ``` - View limits and quotas for *all* namespaces: ```bash kubectl describe namespace ``` ] .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Additional resources - [A Practical Guide to Setting Kubernetes Requests and Limits](http://blog.kubecost.com/blog/requests-and-limits/) - explains what requests and limits are - provides guidelines to set requests and limits - gives PromQL expressions to compute good values <br/>(our app needs to be running for a while) - [Kube Resource Report](https://codeberg.org/hjacobs/kube-resource-report) - generates web reports on resource usage - [nsinjector](https://github.com/blakelead/nsinjector) - controller to automatically populate a Namespace when it is created ??? :EN:- Setting compute resource limits :EN:- Defining default policies for resource usage :EN:- Managing cluster allocation and quotas :EN:- Resource management in practice :FR:- Allouer et limiter les ressources des conteneurs :FR:- Définir des ressources par défaut :FR:- Gérer les quotas de ressources au niveau du cluster :FR:- Conseils pratiques .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-checking-node-and-pod-resource-usage class: title Checking Node and Pod resource usage .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-limiting-resources-in-practice) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-5) | [Next part](#toc-cluster-sizing) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Checking Node and Pod resource usage - We've installed a few things on our cluster so far - How much resources (CPU, RAM) are we using? - We need metrics! .lab[ - Let's try the following command: ```bash kubectl top nodes ``` ] .debug[[k8s/metrics-server.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/metrics-server.md)] --- ## Is metrics-server installed? - If we see a list of nodes, with CPU and RAM usage: *great, metrics-server is installed!* - If we see `error: Metrics API not available`: *metrics-server isn't installed, so we'll install it!* .debug[[k8s/metrics-server.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/metrics-server.md)] --- ## The resource metrics pipeline - The `kubectl top` command relies on the Metrics API - The Metrics API is part of the "[resource metrics pipeline]" - The Metrics API isn't served (built into) the Kubernetes API server - It is made available through the [aggregation layer] - It is usually served by a component called metrics-server - It is optional (Kubernetes can function without it) - It is necessary for some features (like the Horizontal Pod Autoscaler) [resource metrics pipeline]: https://kubernetes.io/docs/tasks/debug-application-cluster/resource-metrics-pipeline/ [aggregation layer]: https://kubernetes.io/docs/concepts/extend-kubernetes/api-extension/apiserver-aggregation/ .debug[[k8s/metrics-server.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/metrics-server.md)] --- ## Other ways to get metrics - We could use a SAAS like Datadog, New Relic... - We could use a self-hosted solution like Prometheus - Or we could use metrics-server - What's special about metrics-server? .debug[[k8s/metrics-server.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/metrics-server.md)] --- ## Pros/cons Cons: - no data retention (no history data, just instant numbers) - only CPU and RAM of nodes and pods (no disk or network usage or I/O...) Pros: - very lightweight - doesn't require storage - used by Kubernetes autoscaling .debug[[k8s/metrics-server.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/metrics-server.md)] --- ## Why metrics-server - We may install something fancier later (think: Prometheus with Grafana) - But metrics-server will work in *minutes* - It will barely use resources on our cluster - It's required for autoscaling anyway .debug[[k8s/metrics-server.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/metrics-server.md)] --- ## How metric-server works - It runs a single Pod - That Pod will fetch metrics from all our Nodes - It will expose them through the Kubernetes API aggregation layer (we won't say much more about that aggregation layer; that's fairly advanced stuff!) .debug[[k8s/metrics-server.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/metrics-server.md)] --- ## Installing metrics-server - In a lot of places, this is done with a little bit of custom YAML (derived from the [official installation instructions](https://github.com/kubernetes-sigs/metrics-server#installation)) - We're going to use Helm one more time: ```bash helm upgrade --install metrics-server bitnami/metrics-server \ --create-namespace --namespace metrics-server \ --set apiService.create=true \ --set extraArgs.kubelet-insecure-tls=true \ --set extraArgs.kubelet-preferred-address-types=InternalIP ``` - What are these options for? .debug[[k8s/metrics-server.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/metrics-server.md)] --- ## Installation options - `apiService.create=true` register `metrics-server` with the Kubernetes aggregation layer (create an entry that will show up in `kubectl get apiservices`) - `extraArgs.kubelet-insecure-tls=true` when connecting to nodes to collect their metrics, don't check kubelet TLS certs (because most kubelet certs include the node name, but not its IP address) - `extraArgs.kubelet-preferred-address-types=InternalIP` when connecting to nodes, use their internal IP address instead of node name (because the latter requires an internal DNS, which is rarely configured) .debug[[k8s/metrics-server.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/metrics-server.md)] --- ## Testing metrics-server - After a minute or two, metrics-server should be up - We should now be able to check Nodes resource usage: ```bash kubectl top nodes ``` - And Pods resource usage, too: ```bash kubectl top pods --all-namespaces ``` .debug[[k8s/metrics-server.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/metrics-server.md)] --- ## Keep some padding - The RAM usage that we see should correspond more or less to the Resident Set Size - Our pods also need some extra space for buffers, caches... - Do not aim for 100% memory usage! - Some more realistic targets: 50% (for workloads with disk I/O and leveraging caching) 90% (on very big nodes with mostly CPU-bound workloads) 75% (anywhere in between!) .debug[[k8s/metrics-server.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/metrics-server.md)] --- ## Other tools - kube-capacity is a great CLI tool to view resources (https://github.com/robscott/kube-capacity) - It can show resource and limits, and compare them with usage - It can show utilization per node, or per pod - kube-resource-report can generate HTML reports (https://codeberg.org/hjacobs/kube-resource-report) ??? :EN:- The resource metrics pipeline :EN:- Installing metrics-server :EN:- Le *resource metrics pipeline* :FR:- Installtion de metrics-server .debug[[k8s/metrics-server.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/metrics-server.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-cluster-sizing class: title Cluster sizing .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-checking-node-and-pod-resource-usage) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-5) | [Next part](#toc-executing-batch-jobs) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Cluster sizing - What happens when the cluster gets full? - How can we scale up the cluster? - Can we do it automatically? - What are other methods to address capacity planning? .debug[[k8s/cluster-sizing.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/cluster-sizing.md)] --- ## When are we out of resources? - kubelet monitors node resources: - memory - node disk usage (typically the root filesystem of the node) - image disk usage (where container images and RW layers are stored) - For each resource, we can provide two thresholds: - a hard threshold (if it's met, it provokes immediate action) - a soft threshold (provokes action only after a grace period) - Resource thresholds and grace periods are configurable (by passing kubelet command-line flags) .debug[[k8s/cluster-sizing.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/cluster-sizing.md)] --- ## What happens then? - If disk usage is too high: - kubelet will try to remove terminated pods - then, it will try to *evict* pods - If memory usage is too high: - it will try to evict pods - The node is marked as "under pressure" - This temporarily prevents new pods from being scheduled on the node .debug[[k8s/cluster-sizing.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/cluster-sizing.md)] --- ## Which pods get evicted? - kubelet looks at the pods' QoS and PriorityClass - First, pods with BestEffort QoS are considered - Then, pods with Burstable QoS exceeding their *requests* (but only if the exceeding resource is the one that is low on the node) - Finally, pods with Guaranteed QoS, and Burstable pods within their requests - Within each group, pods are sorted by PriorityClass - If there are pods with the same PriorityClass, they are sorted by usage excess (i.e. the pods whose usage exceeds their requests the most are evicted first) .debug[[k8s/cluster-sizing.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/cluster-sizing.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Eviction of Guaranteed pods - *Normally*, pods with Guaranteed QoS should not be evicted - A chunk of resources is reserved for node processes (like kubelet) - It is expected that these processes won't use more than this reservation - If they do use more resources anyway, all bets are off! - If this happens, kubelet must evict Guaranteed pods to preserve node stability (or Burstable pods that are still within their requested usage) .debug[[k8s/cluster-sizing.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/cluster-sizing.md)] --- ## What happens to evicted pods? - The pod is terminated - It is marked as `Failed` at the API level - If the pod was created by a controller, the controller will recreate it - The pod will be recreated on another node, *if there are resources available!* - For more details about the eviction process, see: - [this documentation page](https://kubernetes.io/docs/tasks/administer-cluster/out-of-resource/) about resource pressure and pod eviction, - [this other documentation page](https://kubernetes.io/docs/concepts/configuration/pod-priority-preemption/) about pod priority and preemption. .debug[[k8s/cluster-sizing.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/cluster-sizing.md)] --- ## What if there are no resources available? - Sometimes, a pod cannot be scheduled anywhere: - all the nodes are under pressure, - or the pod requests more resources than are available - The pod then remains in `Pending` state until the situation improves .debug[[k8s/cluster-sizing.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/cluster-sizing.md)] --- ## Cluster scaling - One way to improve the situation is to add new nodes - This can be done automatically with the [Cluster Autoscaler](https://github.com/kubernetes/autoscaler/tree/master/cluster-autoscaler) - The autoscaler will automatically scale up: - if there are pods that failed to be scheduled - The autoscaler will automatically scale down: - if nodes have a low utilization for an extended period of time .debug[[k8s/cluster-sizing.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/cluster-sizing.md)] --- ## Restrictions, gotchas ... - The Cluster Autoscaler only supports a few cloud infrastructures (see the [kubernetes/autoscaler repo][kubernetes-autoscaler-repo] for a list) - The Cluster Autoscaler cannot scale down nodes that have pods using: - local storage - affinity/anti-affinity rules preventing them from being rescheduled - a restrictive PodDisruptionBudget [kubernetes-autoscaler-repo]: https://github.com/kubernetes/autoscaler/tree/master/cluster-autoscaler/cloudprovider .debug[[k8s/cluster-sizing.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/cluster-sizing.md)] --- ## Other way to do capacity planning - "Running Kubernetes without nodes" - Systems like [Virtual Kubelet](https://virtual-kubelet.io/) or [Kiyot](https://static.elotl.co/docs/latest/kiyot/kiyot.html) can run pods using on-demand resources - Virtual Kubelet can leverage e.g. ACI or Fargate to run pods - Kiyot runs pods in ad-hoc EC2 instances (1 instance per pod) - Economic advantage (no wasted capacity) - Security advantage (stronger isolation between pods) Check [this blog post](http://jpetazzo.github.io/2019/02/13/running-kubernetes-without-nodes-with-kiyot/) for more details. ??? :EN:- What happens when the cluster is at, or over, capacity :EN:- Cluster sizing and scaling :FR:- Ce qui se passe quand il n'y a plus assez de ressources :FR:- Dimensionner et redimensionner ses clusters .debug[[k8s/cluster-sizing.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/cluster-sizing.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-executing-batch-jobs class: title Executing batch jobs .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-cluster-sizing) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-5) | [Next part](#toc-) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Executing batch jobs - Deployments are great for stateless web apps (as well as workers that keep running forever) - Pods are great for one-off execution that we don't care about (because they don't get automatically restarted if something goes wrong) - Jobs are great for "long" background work ("long" being at least minutes or hours) - CronJobs are great to schedule Jobs at regular intervals (just like the classic UNIX `cron` daemon with its `crontab` files) .debug[[k8s/batch-jobs.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/batch-jobs.md)] --- ## Creating a Job - A Job will create a Pod - If the Pod fails, the Job will create another one - The Job will keep trying until: - either a Pod succeeds, - or we hit the *backoff limit* of the Job (default=6) .lab[ - Create a Job that has a 50% chance of success: ```bash kubectl create job flipcoin --image=alpine -- sh -c 'exit $(($RANDOM%2))' ``` ] .debug[[k8s/batch-jobs.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/batch-jobs.md)] --- ## Our Job in action - Our Job will create a Pod named `flipcoin-xxxxx` - If the Pod succeeds, the Job stops - If the Pod fails, the Job creates another Pod .lab[ - Check the status of the Pod(s) created by the Job: ```bash kubectl get pods --selector=job-name=flipcoin ``` ] .debug[[k8s/batch-jobs.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/batch-jobs.md)] --- class: extra-details ## More advanced jobs - We can specify a number of "completions" (default=1) - This indicates how many times the Job must be executed - We can specify the "parallelism" (default=1) - This indicates how many Pods should be running in parallel - These options cannot be specified with `kubectl create job` (we have to write our own YAML manifest to use them) .debug[[k8s/batch-jobs.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/batch-jobs.md)] --- ## Scheduling periodic background work - A Cron Job is a Job that will be executed at specific intervals (the name comes from the traditional cronjobs executed by the UNIX crond) - It requires a *schedule*, represented as five space-separated fields: - minute [0,59] - hour [0,23] - day of the month [1,31] - month of the year [1,12] - day of the week ([0,6] with 0=Sunday) - `*` means "all valid values"; `/N` means "every N" - Example: `*/3 * * * *` means "every three minutes" - The website https://crontab.guru/ can help to create cron schedules! .debug[[k8s/batch-jobs.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/batch-jobs.md)] --- ## Creating a Cron Job - Let's create a simple job to be executed every three minutes - Careful: make sure that the job terminates! (The Cron Job will not hold if a previous job is still running) .lab[ - Create the Cron Job: ```bash kubectl create cronjob every3mins --schedule="*/3 * * * *" \ --image=alpine -- sleep 10 ``` - Check the resource that was created: ```bash kubectl get cronjobs ``` ] .debug[[k8s/batch-jobs.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/batch-jobs.md)] --- ## Cron Jobs in action - At the specified schedule, the Cron Job will create a Job - The Job will create a Pod - The Job will make sure that the Pod completes (re-creating another one if it fails, for instance if its node fails) .lab[ - Check the Jobs that are created: ```bash kubectl get jobs ``` ] (It will take a few minutes before the first job is scheduled.) .debug[[k8s/batch-jobs.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/batch-jobs.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Setting a time limit - It is possible to set a time limit (or deadline) for a job - This is done with the field `spec.activeDeadlineSeconds` (by default, it is unlimited) - When the job is older than this time limit, all its pods are terminated - Note that there can also be a `spec.activeDeadlineSeconds` field in pods! - They can be set independently, and have different effects: - the deadline of the job will stop the entire job - the deadline of the pod will only stop an individual pod ??? :EN:- Running batch and cron jobs :FR:- Tâches périodiques *(cron)* et traitement par lots *(batch)* .debug[[k8s/batch-jobs.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/k8s/batch-jobs.md)] --- class: title, self-paced Thank you! .debug[[shared/thankyou.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/thankyou.md)] --- class: title, in-person That's all, folks! <br/> Questions?  .debug[[shared/thankyou.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2022-11-live/slides/shared/thankyou.md)]